I’ve have been to Albuquerque, New Mexico several times over the years. One place that I always wanted to go but never managed to was the American International Rattlesnake Museum. They have one of the largest collections of live rattlesnakes in the world. Could it be that whoever I was traveling with didn’t share my enthusiasm?

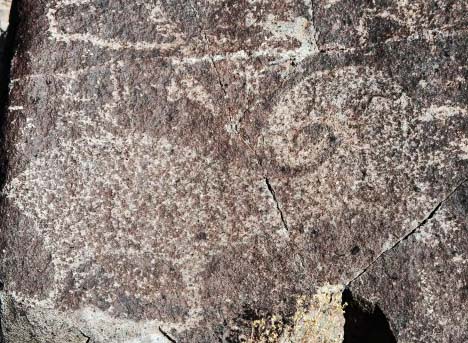

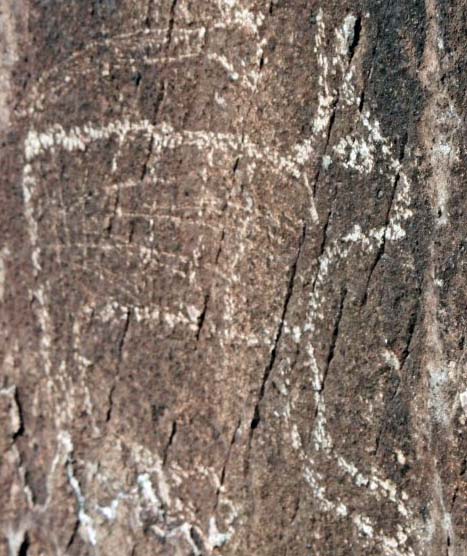

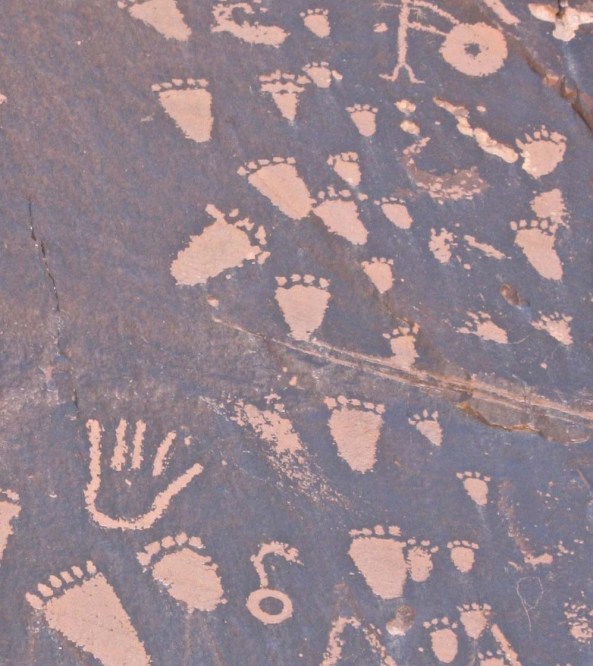

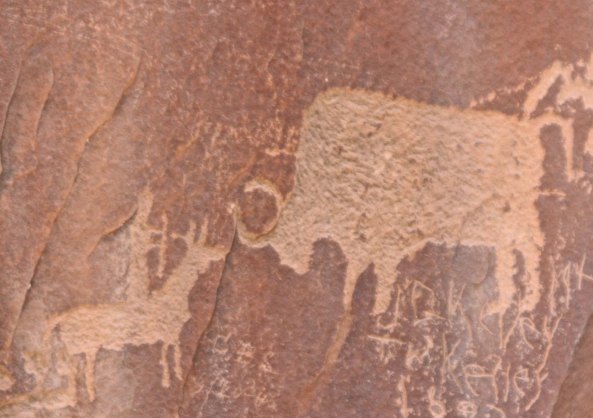

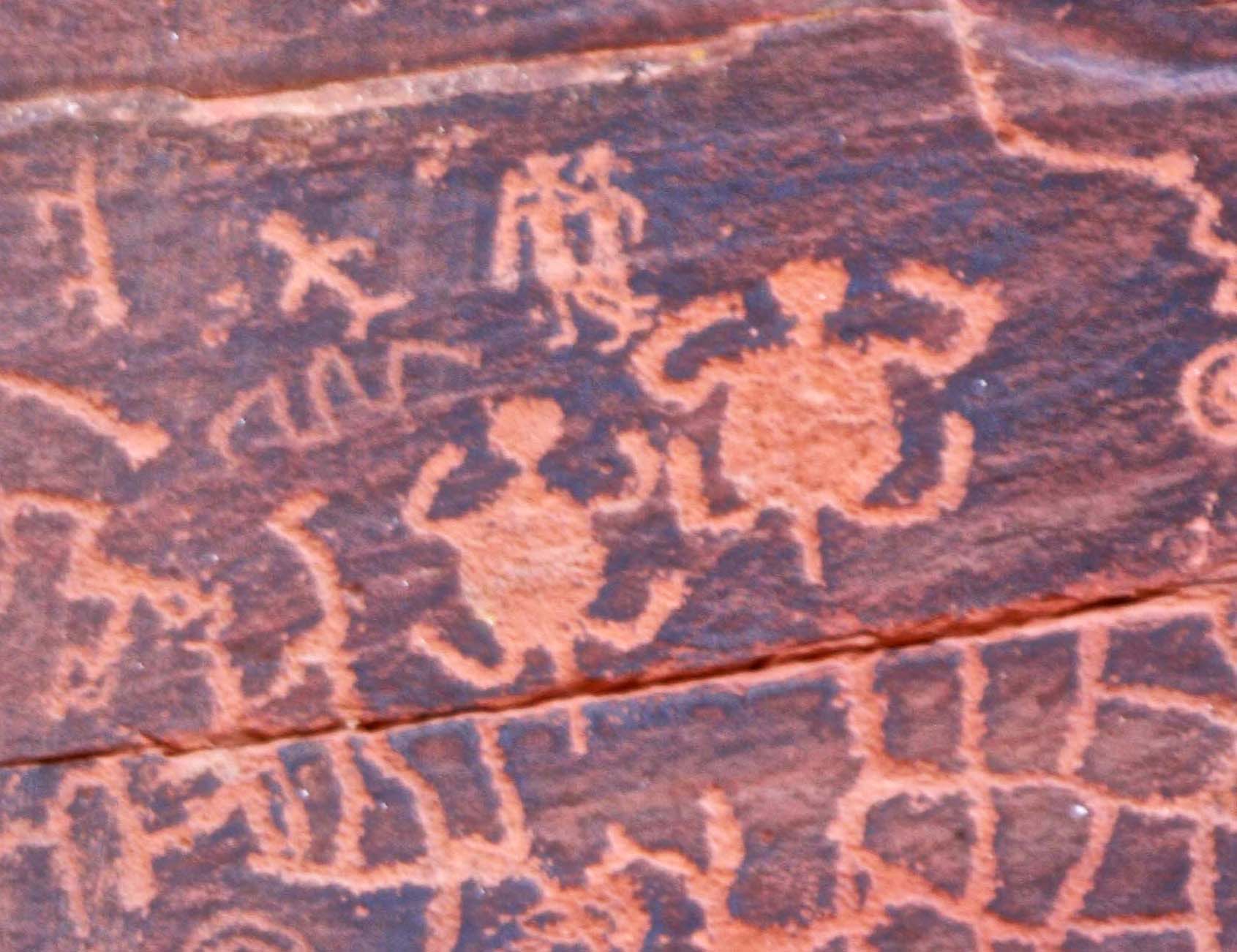

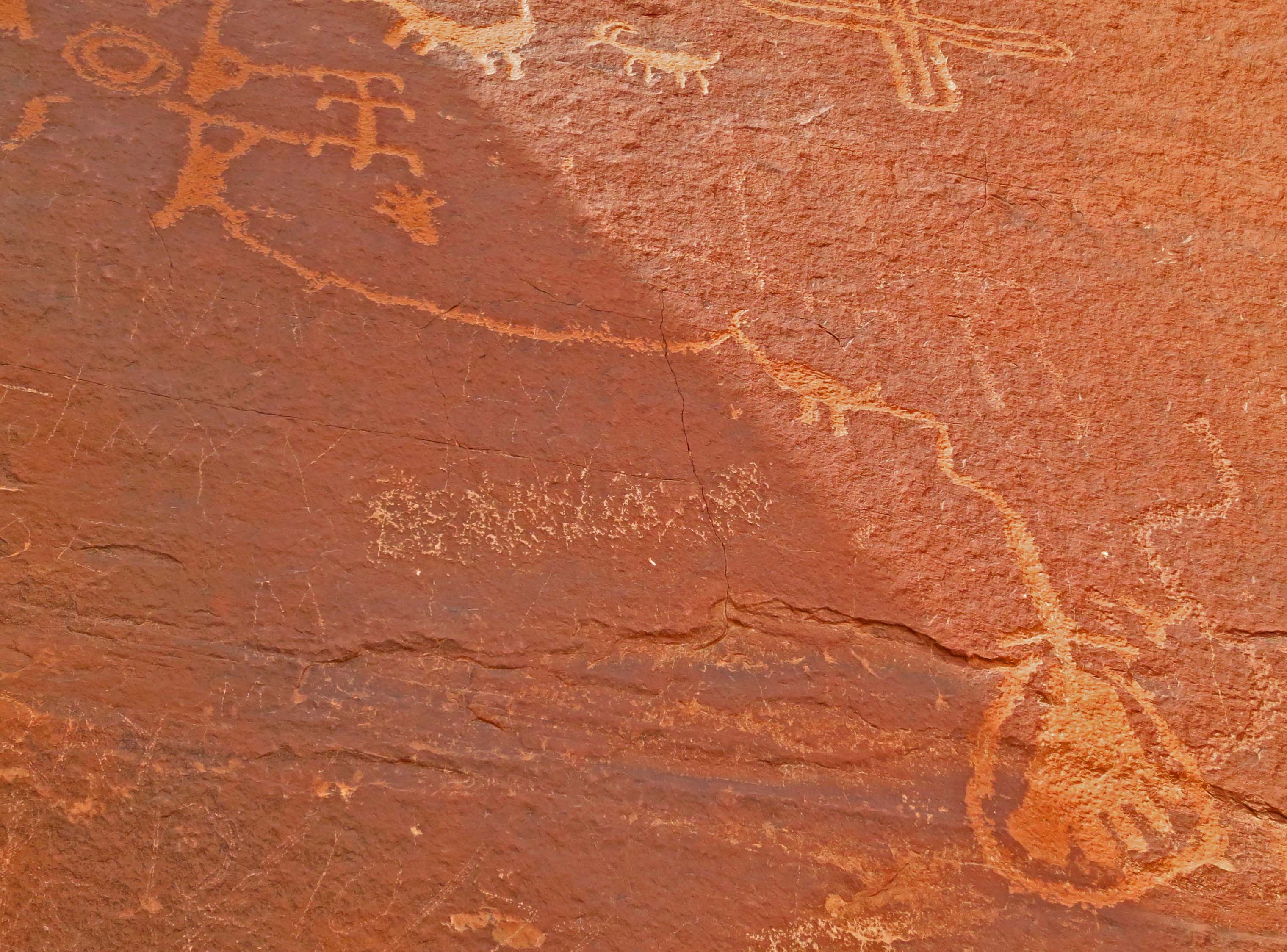

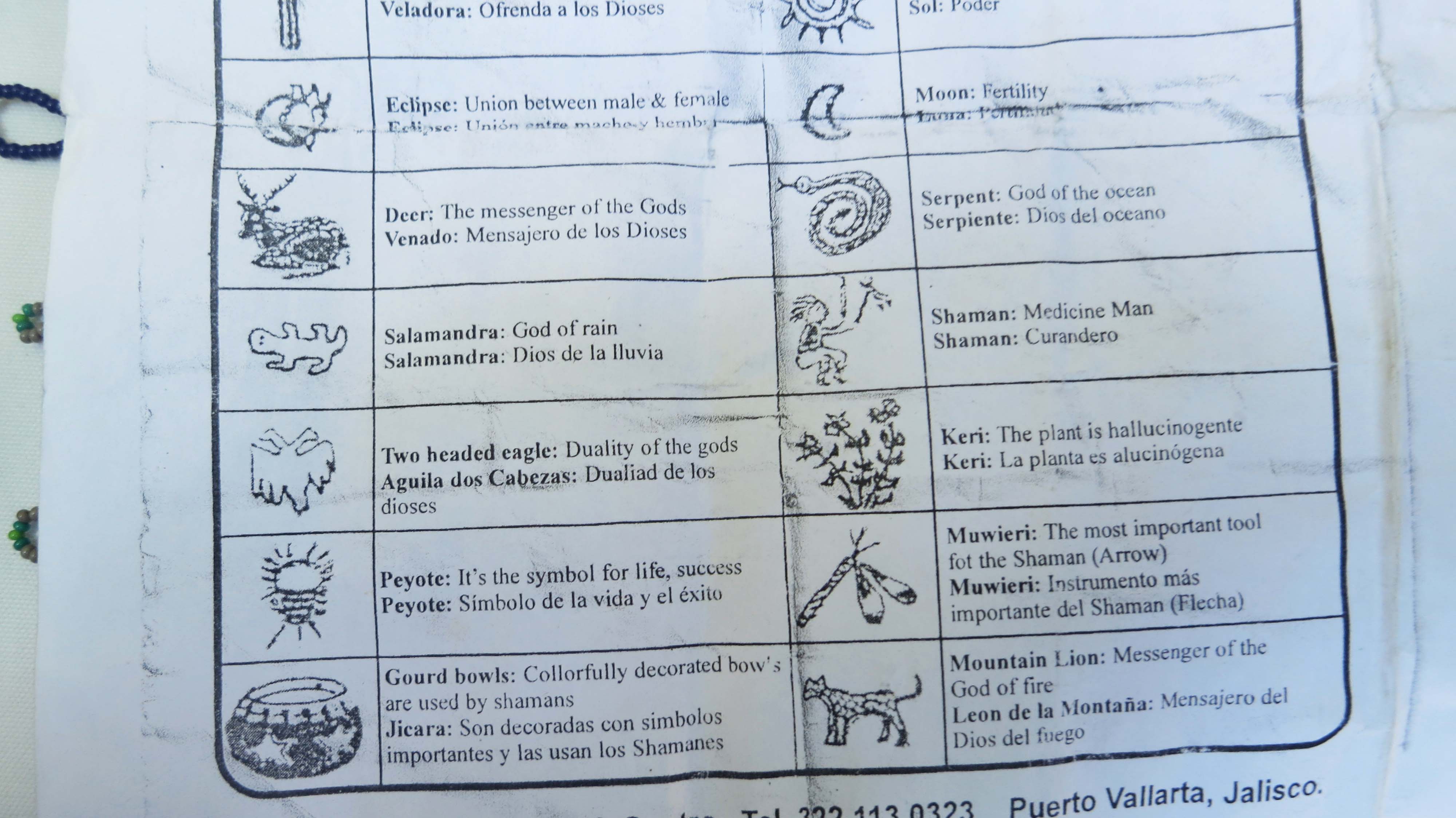

Peggy, however, is game for almost anything and snake images almost always show up among the petroglyphs that fascinate her so much. So off we went to the museum two weeks ago.

That I have a certain ‘fondness’ for rattlesnakes isn’t news to my blog followers. I’ve had numerous encounters with them over the years and have written about several. I’ve even been known to get down on my stomach when they are crawling toward me so I can get better head shots. (Peggy gets a little ouchy about that.) I suspect my attitude would be considerably different if I’d ever been bitten by one. Rattlesnake bites can be deadly, or at a minimum, extremely painful. It’s not something one wants to test.

Fortunately, rattlesnakes come with an early warning system. They rattle. The rattles are made up of keratin, that’s the same thing your fingernails are made of. When irritated, the snake vibrates its tail, knocking its rattles together. It makes a very distinctive sound, one you never forget, one guaranteed to shoot your heart rate up faster that a skyrocket on the 4th of July.

A rattlesnake you see coiled up, rattling its tail, and ready to strike is worrisome, to put it mildly. It’s not a problem, however— as long as you stay clear of its strike zone, which can range from half to two thirds of its body length. For a six foot snake (which is a very big snake), that would be from 3 to 4 feet. If you want to check this out, use a long stick. I have. (Don’t try this at home, kids.)

One you can hear but can’t see is a quantum leap scarier. I stepped on a dead log once ‘that started to rattle’ and found myself an olympic winning 15 feet down the trail before my mind registered snake. There is some evidence that our fear of snakes is instinctive. For example, have you ever come close to stepping on one you didn’t see in advance. Did you find yourself thinking, “snake, maybe I should be concerned.”

When I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in West Africa, I had a cat named Rasputin that proved the hypothesis about fear of snakes. I discovered if I took the old fashioned spring off my back door and rolled it toward him, he would leap 6 feet into the air and land on our couch or other piece of furniture well out of reach from the deadly ’snake.’ Being scientifically oriented, I did it 3 or 4 times just to make sure.

On the other hand, back in California I had a basset hound named Socrates that seemed to counter the theory. I was hiking with him one day at Folsom Lake near Sacramento when I noticed him walk out on to a granite ledge and start sniffing down into the cracks. Suddenly he began barking like the baying hound he was: Loud. Simultaneously, the rock became alive with rattles. Socrates had discovered a rattlesnake den. They can get big, big like in a hundred snakes. Some have even been found with a thousand. Talk about an Indiana Jones’ nightmare…

It was for me, as well. “Socrates, come here!” I demanded. And then again. And again. Each time louder and more desperate. All, to no avail. He just kept barking louder. Damn, that dog could be stubborn. Finally, there was nothing I could do but walk out on the buzzing rock, grab him by the collar, and bodily drag him off. I was lucky I didn’t pee my pants. Had I not immediately put his leash on and pulled him away, he would have gone right back to barking up a storm at the irritated, poisonous serpents.

Here are a few facts on rattlers:

- There are between 32 and 45 species of rattlesnakes, many of which live in the Southwest where Peggy and I just spent five months wandering around outside. They can range in size from 15-24 inches like the pigmy rattlesnake of the South up to close to 8 feet like the eastern diamond back. Peggy’s brother John and his wife Frances found one of these monsters in their backyard in Texas.

- They are superb predators. While lacking an outer ear that would allow them to hear their prey, they have an inner ear that allows them to sense the vibrations of a prey’s movements. Vertical pupils aid in depth perception for strikes and pits on the side of their faces serve as heat detectors which allow rattlers to see their prey in pitch dark situations. Being members of the pit viper family they have large, sharp, hollow fangs that are designed to deliver venom. The fangs fold back against the rattlesnake’s mouth when not in use.

- And finally, here’s a long word for you to impress your friends with: ovoviviparous. It means the rattlesnake mommy hatches her eggs inside of her body and her babies are born alive, ready for action as soon as they can bite their way out of the protective sack they are born in.

And now for a few of the photos we took at the museum.

Plus a couple of snakes that weren’t rattlers, but we were fascinated by their colors.