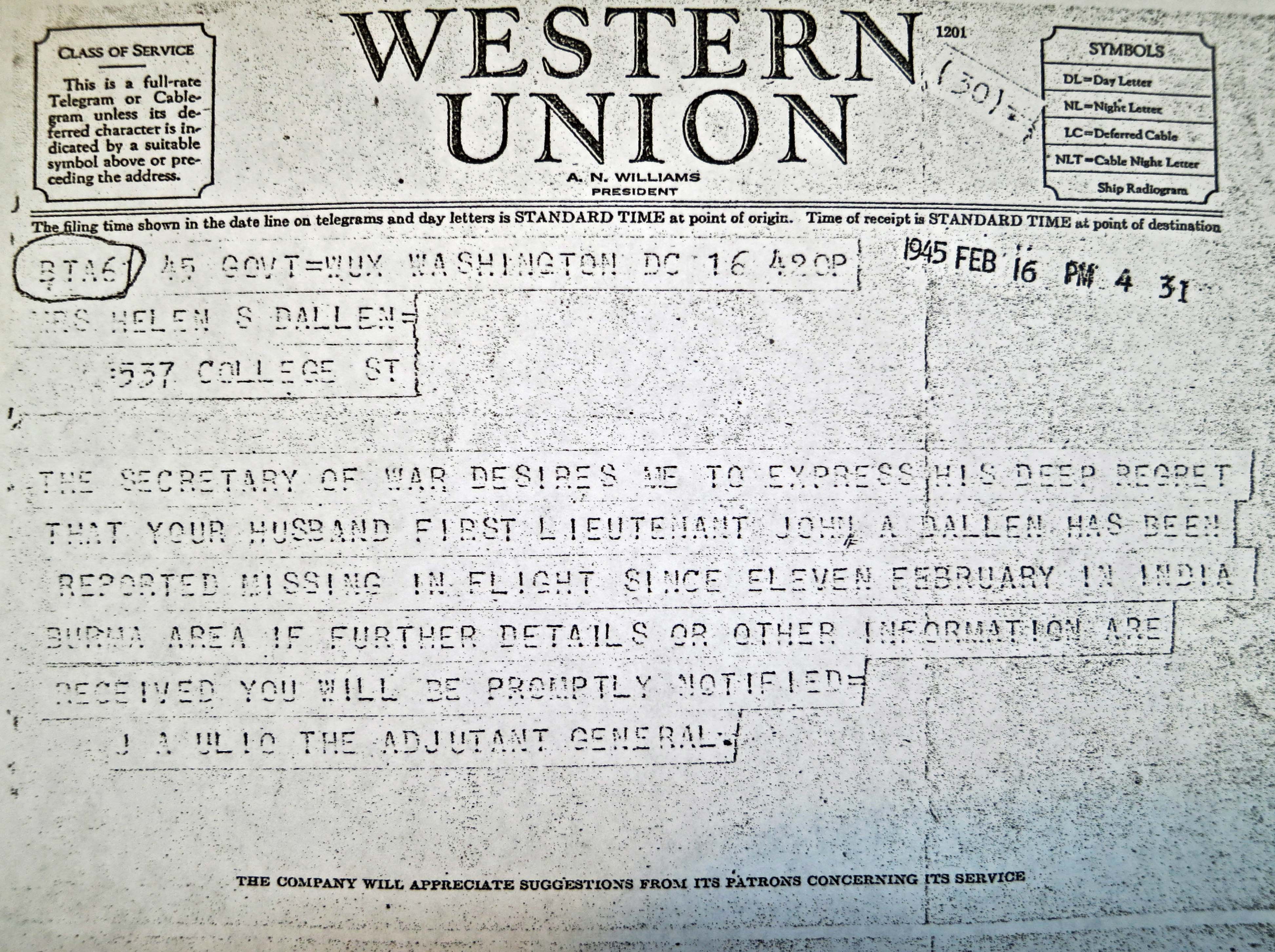

This photo was taken of John immediately after he walked out of the jungle when his plane crashed while he was flying the Hump in World War II. He is holding the boots he wore. His parachute pack is in front.

This is my final post on Peggy’s dad, John Dallen, when he was forced to bail out into Burma jungle when returning from a flight into China across the Himalayan Mountains.

“The conditions were at their worst—raining, pitch black and over territory regarded as plenty rugged. I landed in a jungle so dense that I couldn’t even move. The only sensible thing to do was to pull part of the parachute over me and try to catch some sleep.”

John Dallen in a letter to his wife Helen on February 18, 1945— eight days after he had parachuted out of his damaged C-109 over an Indian jungle when flying the Hump in World War II.

Saturday, February 10, 1945

I left John in my last post as he jumped into the pitch-black night and watched his plane erupt in flames as it went down. Below him was a jungle he couldn’t see. “I had no idea of what I was jumping into,” he reported to his niece Jennifer Hagedorn Mikacich in an oral history. “I hit one layer of the jungle, and then a second, and then a third— crashing through each one and hit the ground hard.” John was battered and bruised but not seriously injured. It was close to midnight.

Catching his breath, and I suspect calming what had to be raw nerves, he pulled out his 45 caliber pistol and fired it into air. John was hoping for a response from his crew members; there was nothing. They had either landed too far away or couldn’t respond. They might be hanging in a tree 100-feet off the ground.

Caught in undergrowth so thick he could barely move, he gathered his parachute around him to stay as dry as possible and tried “to catch some sleep.” At some point in the night he heard a tiger cough.

“Weren’t you afraid, Grandpa?” Jennifer asked.

“I was uneasy,” he confessed some 40 years afterwards. This was Bengal Tiger country and the big males could weigh over 500 pounds and be up 10 feet long. A few, usually older ones who had difficulty catching prey, turned into man-eaters. John had actually seen a record size Bengal Tiger that had been killed because it had been preying on livestock. I’m sure he pictured it in his mind when the tiger coughed.

But John had other concerns as well. The plane had crashed near Nagaland and the Naga were renowned as headhunters. Hump pilots dreaded landing in their territory. The army manual for jungle survival in World War II stated that there were only two areas in Asia where soldiers had to worry about natives: “in New Guinea and certain parts of Burma.” He was quite close to those “certain parts of Burma.” In fact the Naga had a significant presence in the state of Manipur, where his plane had gone down.

Ursula Bower, a pioneering anthropologist in the Naga Hills who became a guerrilla fighter against the Japanese in World War II, noted, “most villages had a skull house and each man in the village was expected to contribute to the collection… There is nothing more glorious for a Naga than victory in battle and bringing home the severed head of an enemy.” Men who failed, she noted, were known as cows. Head hunting by the Naga would continue up until the 1970s and possibly even 80s. John was wise to worry about keeping his head.

A third concern of John’s was that local villagers might turn him over to the Japanese. The US offered rewards to natives who helped downed crews get back to American bases, but the Japanese had a similar program. John might believe he was being led to safety when actually he was being led into a trap.

Sunday, February 11, 1945

All of these thoughts were going through John’s mind the next morning when he awoke at first light and made a pack out of his parachute to carry his Army-issued jungle survival kit. It contained, among other things, water purification tablets, anti-malaria pills, and sulfonamide, the first of the ‘miracle’ drugs discovered that fought bacterial infection. John would use all three. Other standard items in the kit included matches, a compass, a signaling mirror, bouillon/tea, and even fishing gear.

John knew he had to travel west to find US bases and safety. The Japanese were to the east, the Naga to the north, and more jungle to the south. Travelling west was a challenge, however. There are no landmarks in a jungle, only trees and more trees. It is easy to end up traveling in circles. Fortunately, John had a compass and the sun to serve as guides. He also had Boy Scout training, which he would credit later with helping him find his way.

“Part the jungle, don’t push it,” the Army’s World War II jungle survival manual urged. “Keep your head up and your chin in. Try to follow a stream downstream, and try as far as possible to stick to natural trails, or native trails. Don’t try to break your way through.” The best trails, apparently, were elephant trails, jungle freeways three to four feet wide.

John followed the advice— sort of. “I hacked my way through the mess for several hours.” It would have been excruciatingly slow going; especially since the only thing he had to hack with were his hands. The jungle was close to impenetrable. Numerous scratches on his face and hands joined his bruises from the night before. Eventually, he found an animal path that led him to a trail that showed human footprints. And the trail led to a small village.

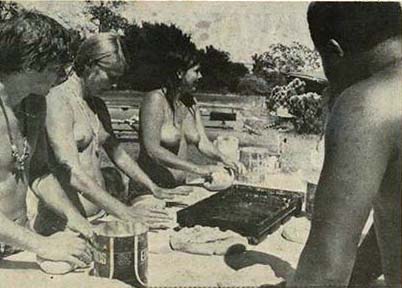

The natives looked quite “primitive,” and dangerous. Armed with machetes, they were dressed only in loincloths. Animal tusks and silver jewelry adorned their ears and body. It seemed, however, that they were friendly. John could keep his head. While none of them spoke English, “A native boy kept pointing in a general direction, which I assumed was the direction for me to follow. He led the way and I gradually picked up quite a following of natives.”

After passing through several small villages, John and his parade came to a village of about 75 inhabitants, where a surprise was waiting: one very excited and worried, co-pilot, Ronald Anderson. “Ron was a big guy, an ex-football player,” John reported. But he hadn’t had John’s luck. His parachute had become entangled in a tree and Ron had to cut himself free, leaving the parachute with its survival kit hanging high above his head. He was genuinely shaken up. Like John, he was battered, bruised and scratched, but he had no serious injuries.

The villagers took John and Ronald to the village headman. Fortunately, a villager was found who could speak some English. Food was generously offered, but John had no idea of what he might be eating; he stuck to bananas and rice. It seems that Ron was equally conservative. That night they slept on sleeping mats next to the headman. Somewhat humorously, John reported in his letter to Helen, “This type of sleeping is ideal for the figure, and even I was sore all over the next morning.”

Monday, February 12, 1945

The headman offered to guide John and Ron on to another village and John woke up early, eager to get started. But he didn’t dare get up.

“I had to pretend sleep because the women of the household were preparing their food in the same room where we were. There are castes in India where the women cannot associate with the men—-especially outsiders— and had I shown signs of awakening, they would have left the room. Eventually they finished and we got up at which time we were offered more rice and the native tea. It is made from a spiced leaf and the liquid content is mostly goat’s milk. I did not touch the rice that morning but did finish the banana from the previous day.” He didn’t report on whether he drank the tea, but he must have been ravenous. At six-foot-two and 150 pounds, John was a skinny guy without an ounce of fat.

When they finally hit the trail, it immediately disappeared into the jungle. They were forced to hike cross-country. Adding to the difficulty of the route, it started to rain again. “We waded down streams for miles and crawled up and down practically impossible hills. Several times we heard planes overhead, but could make no attempt to signal to them because of the thick jungle vegetation overhead.”

(By 1945, sophisticated search and rescue efforts were under way, but the majority of crews that survived crashes still walked out on their own. Many airmen shared John’s experience. During the first three months of 1945 alone, 92 planes crashed while flying the Hump.)

A small village provided a lunch of two hard-boiled eggs. Afterwards, their guides were reluctant to start again. So was John’s co-pilot. The difficult route had begun to wear on him. “Here’s where that Infantry training paid everlasting dividends,” John observed. He was pushing hard, and he was a fast hiker.

“Several times I thought of pulling out my pistol and shooting him.” Ron claimed after they had returned to base.

They arrived at their next destination just at dusk and made a meal of “tea, oranges, bananas, eggs and even cigarettes, such as they were.” The natives were eager to help and would not accept any payment. They were “curious about our complexion, clothes and equipment.” John was amused when a few of the natives tried to break strands from the parachute with their hands. “The look of surprise on their faces was something to see.”

John had even more powerful magic. He was taken to a man whom a tiger had mauled. He treated the wound with sulfonamide. Gangrene had set in, however. John doubted the medicine would do much good, but the villagers were grateful for his effort.

Tuesday, February 13, 1945

“The day’s trip was a repetition of the previous day, possibly a little harder since our muscles were already sore,” John wrote to Helen. At noon they arrived at a village where they met the first and only native “who did not cooperate with us wholeheartedly.” The man had an “extremely mercenary attitude” and wanted to be paid for help. Obviously John and Ron were getting close to civilization.

That night they arrived at a village that was an outpost of the Indian police but the two police officials were away. A young Moslem merchant invited them to his home and fed them nuts and dates while they had “quite the gabfest on India and the British.” They slept that night in the jail under mosquito netting the merchant had loaned them.

Wednesday, February 14, 1945 (I wonder if John realized it was Valentine’s Day?)

The young Moslem provided John and his co-pilot with breakfast the next morning and John provided their host with Atabrine tablets for an attack of malaria he was suffering from. Their host also had another request. Since “most of the natives had never seen a pistol or seen it operate, he asked us to fire a few rounds. When both of us opened up at rapid fire, half of the villagers ran away in alarm— It even frightened our friend.”

With an option of continuing the trip by boat or walking, John chose walking since it would get them out faster. Travelling over relatively flat ground, they hiked 16 miles in 5 hours and arrived at a village where a sub-inspector of police was stationed. A telegraph line ran out of the village and John was able to send a telegram to his CO that he and his co-pilot were alive and well.

Their host that night provided them with their first bath since their ordeal started: “out of a pail of course, but at least the water was hot.” He also offered “some food other than the fruit prepared in a manner we could eat… He had cauliflower tips French fried crisp in butter that was exceptionally good.” John urged Helen to cook some up for herself.

That evening they ended up with a long discussion about India and her problems. “Our British allies ears would burn had they heard some of the opinions expressed about them.” John noted. After eating again, they ‘hit the sack’. “Our host proved that snoring is a universal custom.”

Thursday, February 15, 1945

The trip the next morning had a twist. They rode on an elephant. “I believe it was the hardest part of the trip,” John whined to Helen. “The animal is rather broad-beamed as you can imagine and even my legs couldn’t quite make the spread.” He jokingly reported in his oral interview with Jennifer that he was “worried for his manhood.”

An English tea plantation was waiting for him at the end of the journey, however. John found it “remarkable to find a veritable mansion stuck in this wilderness.” A drink was immediately placed in his hand and a meal ordered. “The house was spotless with beautiful furniture and silverware all around. There were acres of lawn, flowerbeds and even a stable of polo ponies. The servants were perfectly trained and dressed as if from a scene in Arabian Nights.”

Even more welcoming, after they had washed up and eaten, the plantation manager gave them a ride in his truck to the nearby airbase of Shamshernagar. The ordeal had ended.

John’s first acts were to borrow some clean clothes and have a hot shower. After “a meal of real American food and not a few drinks under my belt, I dropped you a line which I certainly hope reached you in the fastest possible time.”

The letter that John wrote to Helen immediately after walking out from the airplane crash. He had hoped that the letter would reach her before the telegram announcing that he was missing in action. It didn’t.

On returning to his base at Kurmitola, John learned that “the rest of my crew turned up a few days later after having a much easier time of it. They landed on a mountainside and had practically a road all the way to a base. As a matter of fact the last few days were a lark to them, having spent them at a most hospitable tea planter’s estate. Personal servants, meals in bed, etc. I could kick myself for having worried about them so much.”

John was given a week’s R&R in Ceylon and then returned to his flying duties. He would fly 55 more missions across the Hump. On July 26 he transferred to Tezgaon (now in Bangladesh). Every flight from that point on was in a C-54. His last flights were on September 26, 1945 from Shanghai to Liuchow to Tezgaon, piloting a C-54 for seven hours of daylight flying, four of nighttime flying, with two hours on instruments. He had logged 2788 hours since his first student flight.

I would like to conclude with a special thank you to John’s son, John Dallen Jr., our son, Tony Lumpkin, and my friend Mike Sweeney for helping in the research for my three blogs on the Hump pilots.

In 1996 China invited Hump pilots and crews back to China to honor their World War II efforts and establish a memorial in Kunming. John is in the middle of the lower row next to the woman with the dark blouse.

John and Peggy on the American River in Sacramento in 2006. Every Wednesday, I was privileged to pick John up and take him for a walk on the river. Even in his late 80’s, he still loved to hike.