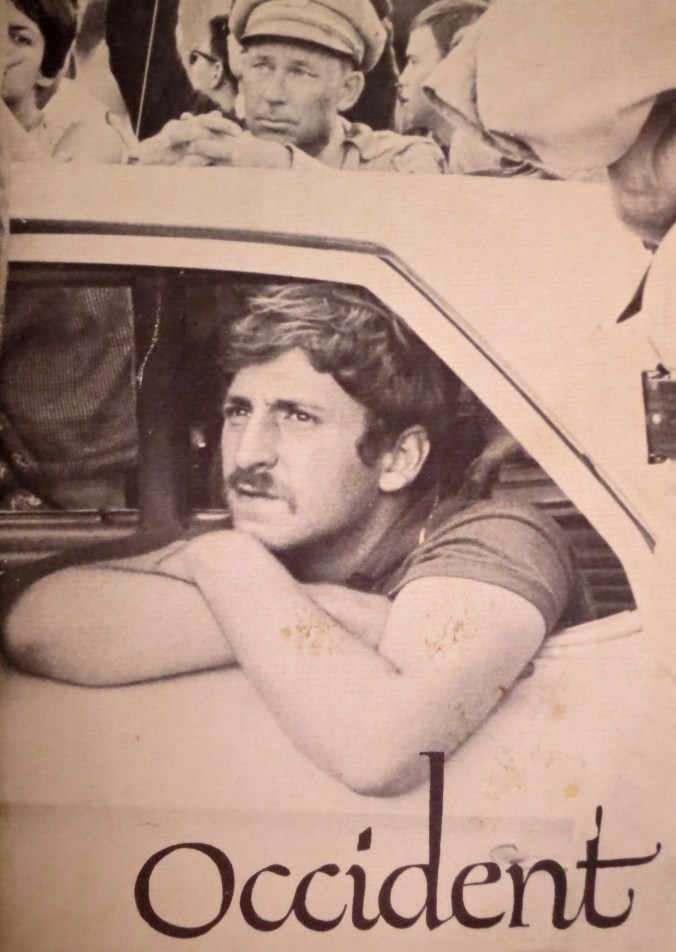

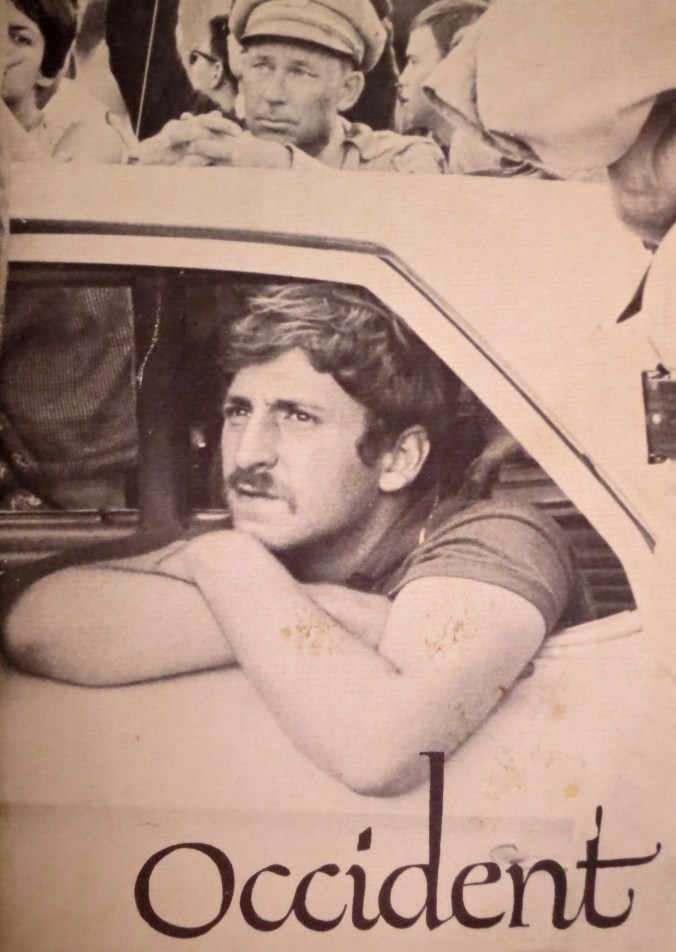

Jack Weinberg looks out the window of a police car on Sproul Plaza on the Berkeley Campus. He had been arrested for signing up students to support the Civil Rights Movement. Jack was the person who coined the rally cry of the 60s: “Never trust anyone over 30.” (Photo was on the front of Berkeley’s literary magazine, Occident.)

I came back to Berkeley in the fall of 1964 with a new living arrangement. Before summer break, two of my dorm-mates, Cliff Marks and Jerry Silverfield, had agreed to share an apartment with me for our senior year. Landlords had a captive student population to exploit so prices were high. We ended up with a small kitchen, bathroom, living room, and bedroom. Things were so tight in the bedroom that Cliff and I had a bunk bed. He got the top. I would later wonder why this was superior to dorm life. We had more responsibility and less privacy.

We christened the apartment by consuming a small barrel of tequila Cliff had brought back from his summer of sharpening Spanish skills in Mexico. While Cliff, Jerry and I were recovering from our well-deserved headaches, the Administration moved decisively to eliminate on-campus political activities. There would be no more organizing of community-oriented demonstrations from campus, no more collecting of money from students to support causes, and no more controversial speakers on campus without administrative oversight and control. The Bancroft-Telegraph entrance free speech area was out of business, closed down, caput. That incredible babble of voices advocating a multitude of causes would be heard no more.

The Administration’s actions were a testament to the success of the Civil Right’s struggle taking place in the Bay Area. It wasn’t that the activists wanted change; the problem was that they were achieving it. Non-violent civil disobedience is a powerful tool. Base your fight on moral issues; use the sit-in and the picket line to make your point. When the police come, don’t fight back; go limp. If they beat you over the head, you win. Sing songs of peace and justice; put a flower in the barrel of the weapon facing you. It is incredibly hard to fight against these tactics.

As the protests in the surrounding community became more successful, the power structure being attacked struck back. Calls were made to the Regents, the President of the University system, and the Chancellor at Berkeley. ‘Control your students or else’ was the ominous message. One of the people making the threats was William Knowland, owner of the Oakland Tribune and a former Republican Senator from California who had been a strong supporter of McCarthyism. The Tribune was one of the targets of the anti-discrimination campaign.

The Regents, President and Chancellor bowed to the pressure. Some members of the Administration undoubtedly agreed with Knowland and saw the protesters as part of an anarchic left-wing plot. Others may have believed that the students’ effectiveness would bring the powers that be down on the university. Academic freedom could be lost. Some likely felt that the activities were disruptive to the education process and out-of-place on a college campus.

One thing was immediately clear; the Administration woefully underestimated the reaction of the leaders of the various organizations and large segments of the Campus population to its dictum. Maybe the administrators actually believed the message they had received from their student leadership the previous fall or maybe they just needed to believe: the outside pressure was so great it didn’t matter how students reacted.

But react they did. These were not young adults whose biggest challenge had been to organize a pre-football game rally. Some, like Mario Savio, had walked the streets of the South and stared racism in the face, risking their lives to do so. That summer while I was driving a laundry truck over the Sierras, three of their colleagues had been shot dead and buried under an earthen dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Many had cut their political eye teeth four years earlier in the anti House Un-American Activities Committee demonstrations in San Francisco and had participated in the numerous protests against racial discrimination since. They understood the value of demonstrations, media coverage and confrontation, and had become masters at community organization. They were committed to their beliefs and were willing to face police and be arrested if necessary.

The Administration wasn’t nearly as focused. Mainly liberal in nature and genuinely caring for its students, it utilized a 50’s mentality to address a 60’s reality. Its bungling attempts to control off-campus political activity combined with its inability to recognize the legitimacy and depth of student feelings would unite factions as diverse as Young Republicans for Goldwater with the Young People’s Socialist League and eventually lead to the massive protests that would paint Berkeley as the nation’s center of student activism and the New Left. Over the next three months I would spend a great deal of time listening, observing and participating in what would become known world-wide as the Free Speech Movement. As a student of politics, I was to learn much more in the streets than I did in the classroom.

What evolved was a classic no win, up-against-the-wall confrontation. The Administration would move from “all of your freedoms are removed,” to “you can have some freedom,” to “let’s see how you like cops bashing in your heads.” The Free Speech leaders would be radicalized to the point where no compromise except total victory was acceptable. Student government and faculty solutions urging moderation and cooperation would be lost in the shuffle. Ultimately, Governor Pat Brown would send in the police and Berkeley would take on the atmosphere of a police state.

The process of alienation that had started for me with the student leader conference in 1963 continued to grow, but I never made the leap from issue to ideology. It was no more in my nature to be left-wing than it had been to be right-wing. However, I would journey across the dividing line into civil disobedience.

Within hours of the time that Dean Katherine Towle sent out her ultimatum to campus organizations, the brother and sister team of Art and Jackie Goldberg had pulled together activist organizations ranging in orientation from the radical to conservative and a nascent FSM was born. Shortly thereafter the mimeographs were humming and students were buried in an avalanche of leaflets as they walked on to campus. I read mine is disbelief. The clash I had foreseen a year earlier had arrived. There was no joy in being right.

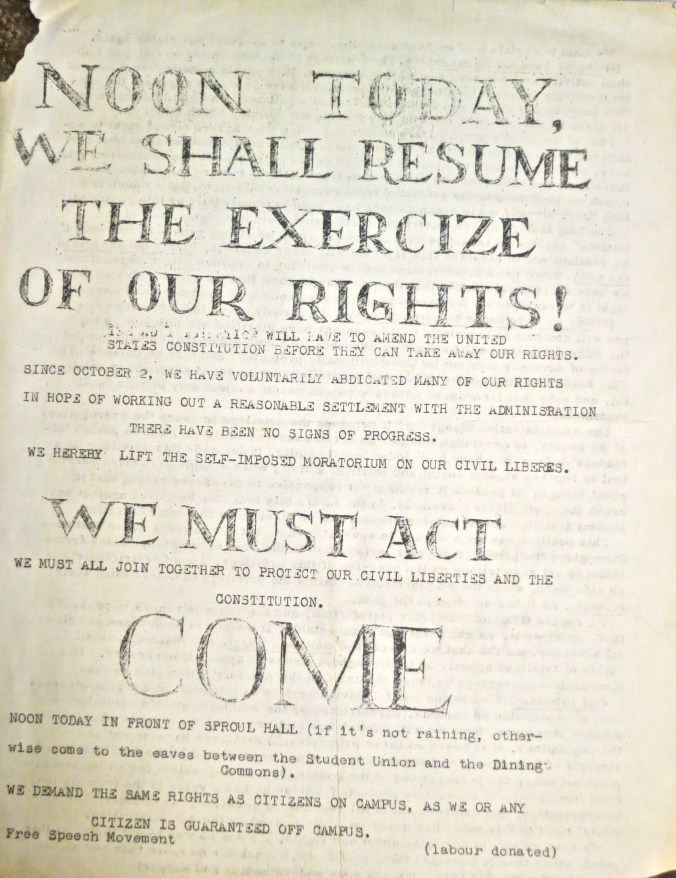

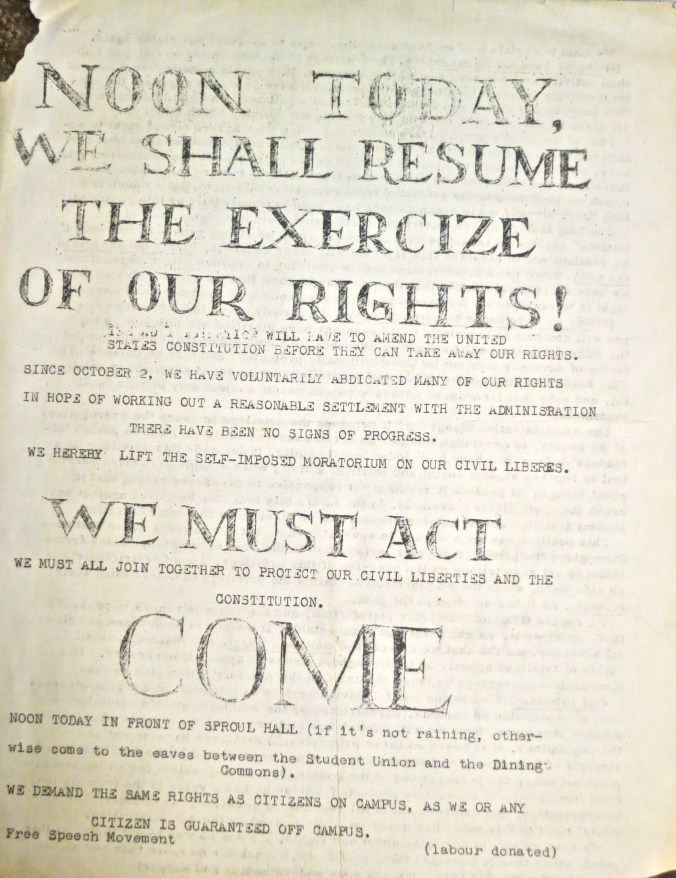

Hastily run off mimeograph sheets such as this one kept students up-to-date on what was happening with the Free Speech Movement. It seems terribly quaint in the age of the Internet and cellphones.

As soon as it became apparent that the Administration had no intention of backing off from its new rules, the FSM leadership determined to challenge the University. Organizations were encouraged to set up card tables in the Sather Gate area to solicit support for off campus causes. I had stopped by a table to pick up some literature when a pair of Deans approached and started writing down names of the people manning the table. Our immediate reaction was to form a line so we could have our names taken as well. The Deans refused to accommodate us. The Administration’s objective was to pick off and separate the leadership of the FSM from the general student body.

A few days later, on October 4, I came out of class to find a police car parked in Sproul Plaza surrounded by students. The police, with encouragement from the Administration, had arrested Jack Weinberg, a non-student organizer for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) who had been soliciting support for his organization. Someone had found a bullhorn and people were making speeches from the top of the police car while Jack sat inside. I situated myself on the edge of the fountain next to the Student Union and idly scratched the head of a German Short Haired Pointer named Ludwig while I listened. Ludwig visited campus daily and played in the water. He’d become a Berkeley regular.

Eventually I stood up and joined those on the edge of the crowd thereby becoming a part of the blockade. It was my first ever participation in civil disobedience. It was a small step. There would be plenty of time for more critical thinking if the police showed up in force. I did duty between classes and took breaks for eating and sleep. Eventually, after a couple of days, the FSM negotiated a deal with the Administration. Jack was booked on campus and turned loose, as was the police car. A collection was taken up to pay for minor damages the police car had sustained in the line of duty while serving as a podium. I threw in a dollar. Weinberg, by the way, was the one who coined the rallying cry of youth in the 60s: “Never trust anyone over 30.”

The situation did not improve. Each time a solution seemed imminent, the Administration would renege or the FSM would increase its demands. In addition to the right to organize on campus, the disciplining of FSM leaders became a central issue. Demonstrations took place almost daily and were blasted in the press, which wasn’t surprising considering the local press was the Oakland Tribune. I learned a great deal about media sensationalism and biased reporting. One day I would sit in on a very democratic and spirited discussion of the pros and cons of a specific action and the next day I would read in the Tribune or San Francisco Examiner that I had participated in a major insurrection of left leaning radicals who were challenging the very basis of law and order and civilized society.

Older adults, looking suspiciously like plain-clothes policemen or FBI agents, became a common occurrence on Campus. It was easy to become paranoid. If we signed a petition, demonstrated, made a speech or just stood by listening, would our pictures and names end up in some mysterious Washington file that proclaimed our disloyalty to the nation? These weren’t idle thoughts. A few years earlier people’s careers had been ended and lives ruined because someone had implied they were soft on communism. J. Edgar Hoover was known for tracking Civil Rights’ leaders and maintaining extensive files on every aspect of their lives. While we weren’t up against the KGB, caution was advisable. We looked warily at those who didn’t look like us. One day a small dog was making his way around the edge of the daily demonstration, sniffing people.

“See that Chihuahua,” a friend whispered in my ear. I nodded yes. “It’s a police dog in disguise. Any moment it is going to unzip its front and a German Shepherd will pop out.”

The wolf in sheep’s clothing was amongst us. It was a light moment to counter a serious time. And we were very serious. I sometimes wondered when the celebrated fun of being a college student would kick in.

One day I was faced with a test more serious than any I had ever faced in the classroom. On Friday, December 3, 1964, FSM leaders called for a massive sit in at Sproul Hall. Once again communication had broken down and the Administration was back peddling, caught between students and faculty on the one side and increasing pressure from the outside on the other. I thought about the implications of the sit-it and decided to join. It was partly on whim, and partly because I had a need to act. For three months I had listened to pros and cons and watched the press blatantly misrepresent what was happening on campus. I was angry, knowing that the public had little option but to believe we were being manipulated by a small group of radicals and had no legitimate concerns.

It was not wrong to utilize an edge of campus for discussing the central issues of the day, or for organizations to raise funds for supporting various causes, or even to recruit students to participate in efforts to change the community. It didn’t disrupt my education. I was free to stop and listen, to join in, or pass on. What it did do was irritate powerful, established members of the community. And for that reason, our freedoms had been curtailed.

Maybe if enough students joined together and the stakes were raised high enough, the Administration would listen, the press would dig a little deeper, and our basic freedoms would be returned. I told my fiancé I was going inside and then joined the thousand or so students who had made similar decisions. It was early in the afternoon and we were in high spirits. I believed it would be hard for the Administration to claim 1000 students were a small group of rabble-rousers bent on destroying the system. And I was right. They claimed we were a large group of rabble-rousers bent on destroying the system.

Inside I was treated to one of the more unique experiences of my life. The sit-in was well-organized. Mario Savio and other FSM leaders gave us directions on what to do if the police arrived. There were clear instructions that we were not to block doorways. The normal business of the University was not to be impeded and we were not to be destructive in any way. Floors were organized for different purposes. The basement was set aside as the Free University where graduate students were teaching a variety of classes. These included normal topics such as physics and biology and more exotic subjects such as the nature of God. One floor was set aside as a study hall and was kept quiet. Another floor featured entertainment – including old Laurel and Hardy films.

After administrators left, the Dean’s desk became a podium for speech making. I felt compelled to participate. There was a long line of speakers. We were required to take off our shoes so the desk wouldn’t be damaged. The real treat though was an impromptu concert by Joan Baez. I joined a small group sitting around her in the hallway and sang protest songs. The hit of the night was “We Shall Overcome.” It provided us with a sense of identification with struggles taking place in the South. I felt like I belonged and was part of something much larger than myself. Mainly I walked around and listened, taking extensive notes on what I saw and felt. Later I would sit in the Café Med and write them up. They would become the basis of talks I would give back home over the Christmas break.

Along about midnight I started thinking about my comfortable bed back in the apartment. The marble floors of Sproul Hall did not make for a good night’s sleep and it appeared the police weren’t coming, at least in the immediate future. Yawning, I left the building and headed home. I would come back in the morning.

I did, but I came back to a semi-police state. Berkeley was an occupied campus. Armed men in uniforms formed a cordon around the Administration Building where students were being dragged down the stairs and loaded into police vans. Windows had been taped over so people or media could not see what was transpiring inside. The great liberal governor of California had acted to “end the anarchy and maintain law and order in California.”

I am sure Laurel and Hardy would have seen something to laugh about. Dragging kids down stairs on their butts while their heads bounced along behind could easily have been a scene in one of the old Keystone Cop films. The Oakland police weren’t nearly as funny as the Keystone Cops, however. As for Clark Kerr, President of the University, he felt we were getting what we deserved and argued that the FSM leaders and their followers “are now finding in their effort to escape the gentle discipline of the University, they have thrown themselves into the arms of the less understanding discipline of the community at large.”

An aging copy of the Daily Cal, Berkeley’s student newspaper, announces the arrests at Sproul Hall on December 4, 1964.

Later Kerr claimed he had an understanding with Governor Brown to let the students remain in Sproul Hall over night. He would talk with the protesters in the morning in an effort to end the sit-in peacefully. But Brown reneged on the agreement. One report was that Edwin Meese, Ronald Reagan’s future Attorney General and, at the time, Oakland’s Deputy DA and FBI liaison, had called Brown in the middle of the night with the claim that student’s were destroying the Dean’s office.

I had participated in the “destruction,” i.e. stood on the Dean’s desk in my socks. Either the DA had received an erroneous report or he had deliberately lied to the Governor. My sense was that the right-wing of American politics, which Meese represented, had much more to gain from violent confrontations than it did from negotiated settlements.

The campus came to a grinding halt and a great deal of fence-sitting ended. Whole departments shut down in strike. Sproul Hall plaza filled with several thousand students in protest of the police presence. When the police made a flying wedge to grab a speaker system FSM was using, we were electrified and protected the system with our bodies. It was the closest I have ever come to being in a riot; thousands of thinking, caring students teetered on the edge of becoming an infuriated, unthinking mob. Violence and bloodshed, egged on by police action, would have been the result. Kerr, Brown, Knowland and company would have had the anarchy they were claiming, after the fact. A few days later we were to come close again.

Kerr, in a series of around the clock meetings with a select committee of Department Chairs, had arrived at a compromise he felt would provide for the extended freedom being demanded on campus while also diffusing the outside pressure to crack open student heads. Sit-in participants arrested in the Sproul Hall would be left to the tender mercies of the outside legal system and not disciplined by the University. Rights to free speech and organization on campus would be restored as long as civil disobedience was not advocated.

Kerr and Robert Scalapino, Chair of the Political Science Department, presented the compromise to a hastily called all-campus meeting of 15,000 students and faculty at the Greek Theater. There was to be no discussion and no other speakers. When Mario Savio approached the podium following the presentation, he was grabbed by police, thrown down, and dragged off the stage. Apparently he had wanted to announce a meeting in Sproul Plaza to discuss Kerr’s proposal. Once again, Berkeley teetered on the edge of a riot. We moved from silent, shocked disbelief to shouting our objections. Mario, released from the room where he was held captive, urged us to stay calm and leave the area. We did, but Kerr’s compromise had become compromised.

A full meeting of the Academic Senate was to be held the next day and the whole campus waited in anticipation to hear what stand Berkeley’s faculty would take. We knew that most faculty members deplored the presence of police on campus and the violent way they had responded to the nonviolent demonstrators. Dragging Mario off the stage had not helped the Administration’s case. Some departments such as math, philosophy, anthropology and English were clearly on the side of FSM while others including business and engineering were in opposition.

My own department of political science was clearly divided. Some professors believed that nonviolent civil disobedience threatened the stability of government. Others recognized how critical it was for helping the powerless gain power. To them, having large blocks of disenfranchised, alienated people in America seemed to be a greater threat to democracy than civil disobedience.

The Senate met on December 8 in Wheeler Hall. Some 5000 of us gathered outside to wait for the results and listen to the proceedings over a loud speaker.

To the students who had fought so hard and risked so much, and to those of us who had joined their cause, the results were close to euphoric. On a vote of 824-115 the faculty voted that all disciplinary actions prior to December 8 should be dropped, that students should have the right to organize on campus for off-campus political activity, and that the University should not regulate the content of speech or advocacy. Two weeks later, the Regents confirmed the faculty position.

We had won. Our freedom of speech, our freedom to organize, and our freedom to participate in the critical issue of the day were returned. While we were still a part of the future so popular with commencement speakers, we were also a part of the now, helping to shape that future.

NEXT BLOG: The aftermath of the Free Speech Movement and a 50-year perspective on the results.