After a day of teaching at Gboveh High School, I would follow jungle trails to surrounding villages and farms. This picture features a Kpelle farmer I met along with his three boys and young daughter. Harvested rice is piled behind the family.

In some ways our everyday life as high school teachers resembled our everyday life as elementary school teachers. We would crawl out of bed at 6:30, eat a quick meal and walk to school. Shortly after 1:00 we would be home downing peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with the school day finished. Our nap was next.

The new location encouraged wandering. After siesta, the dogs and I would disappear into the jungle. This continued a tradition of hiking in the woods from my earliest childhood years. I explored the surrounding village trails going farther and farther afield. Sometimes I would take my compass so I could draw primitive maps and figure out where I had been. Tribal folks were surprised to find me out in the bush but were always friendly.

I discovered where the cane fields and whiskey stills were, found a primitive but well-built wooden bridge across the river, made my first acquaintance with Driver Ants, and avoided the numerous poison snakes.

Sometimes Jo Ann would join me and on occasion I would take Sam, other Volunteers and Peace Corps staff along. The hikes provided an opportunity to explore aspects of tribal life not normally found in Gbarnga. They also served as a major part of my exercise program. I became svelte, or maybe just skinny.

A Kpelle woman and her daughter take turns pounding palm nuts in this 1966 photo taken near Gbarnga, Liberia.

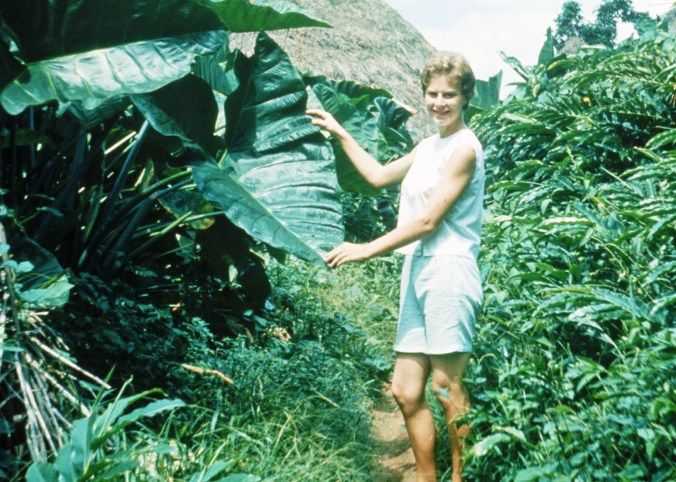

Jo Ann holds an Eddo or Taro leaf. The tubers of this plant are used as food throughout the tropics.

Hidden by palm fronds, I climb up a Kpelle ladder I discovered on one of my jungle hikes. Notches in the trunk served as rungs for the primitive but effective climbing device.

Our social life was nothing to write home about. Unlike single Peace Corps Volunteers, we had each other for amusement. We did maintain our friendship with other married couples. Occasionally students or teachers would drop by. Sam was always hanging around, even when not working. I maintained an ongoing chess game with the minister of the Presbyterian mission. We would send our house boys back and forth with moves.

The largest social event we hosted was a goat feast for our fellow teachers from the high school and elementary school. Between finding a goat, having it slaughtered and making soup, it turned into a major project. Three women teachers from the elementary school came over to help with the cooking chores. They wanted to make sure the goat was properly cooked. The soup along with rice was delicious, and plenteous. No one went home hungry, or sober for that matter. I’d bought two cases of club beer and one case of Guinness Stout to accompany dinner. Drunk driving was not an issue. No one owned a car.

Even with everyone stuffed, there was ample goat chop left over to feed the dogs for a week. It lasted a night. Liberian dogs always ate like they were on the edge of starvation, even fat Liberian dogs. Somewhere in the midst of the four-legged feeding frenzy, I heard a yip and went outside to find that Brownie Girl had shoved a goat bone through her cheek. The medical emergency was minor; her real concern was being knocked out of the action. The other dogs and Rasputin were gobbling down her share. I pulled the bone out and Brownie Girl jumped back into the fray. It was pure greed. Not a scrap was left in the morning.

One of my favorite pastimes was to sit outside in the late afternoon, drink a gin and tonic, and watch the incredible tropical lightning storms. We found a jeep seat somewhere that made a comfortable couch for our porch. On occasion the sky would turn an ominous black and we could hear the storm as it ripped through the rainforest. The impending mini-hurricane would send Jo and I scurrying to yank clothes off the clothesline and batten down the hatches, i.e. make sure doors and shutters were firmly closed.

Dark storm clouds like these over Gbarnga suggested it was time for Jo Ann and I to quickly take in the laundry and shut up our house.

Every month or so, we would visit Monrovia for a touch of city life. Eating at the French restaurant by candlelight, spending an hour in the air-conditioned super market, hanging out in a book store or seeing the latest movie did wonders for morale. It almost made up for the three to four-hour harrowing taxi ride. We even took Sam with us once for his ‘birthday.’ He really didn’t know when it was so we declared it was during the trip. He still uses the same birth date.

Our really big break from teaching was a one-month trip to the big game parks of East Africa. In my next blog I will feature facing elephants and lions and water buffalo in a Volkswagen beetle, Oh My.