Peggy and I are now back at home in Oregon after our ten week 8,000 mile road trip around the US in our small RV. It was weird out there in the Age of Coronavirus— but interesting. As much as possible, we stayed off of freeways and traveled by backroads, many of them significant to America’s history. One such road we followed was a portion of US 30 across Nebraska following the South Platte River. The route was once a path for Native Americans and mountain men. Later, it became a section of the Oregon Trail that pioneers and gold seekers followed in the mid-1800s on their way west in search of wealth or a new life. In 1913, it became part of America’s first transcontinental road, the Lincoln Highway.

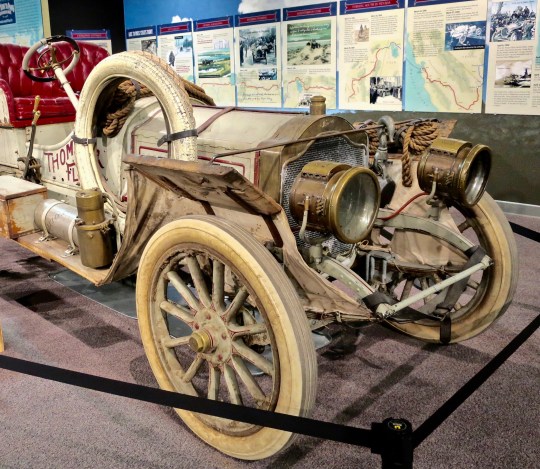

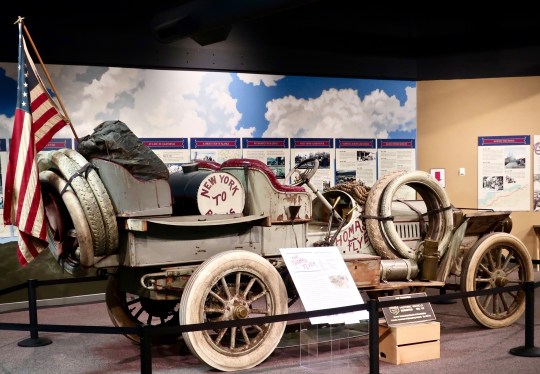

I was excited to learn that it was also a section of route that the 1908 Great Automobile Race from New York City to Paris followed through Nebraska. I had first developed an interest in the race when I learned about it in the remote Nevada towns of Tonopah and Goldfield where it had been the biggest thing to happen to them since the discovery of gold. My interest was peaked considerably last summer when I found America’s original entry, the Thomas Flyer, in the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada. Since then I have read several articles on the race and discovered a treasure trove of photos from the Library of Congress. It’s a story that has been told many times but is worth retelling, which I will do over my next 3-4 posts. I figure it will serve as a kick-off for my posts on our road trip!

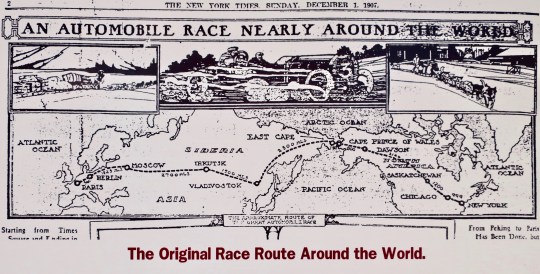

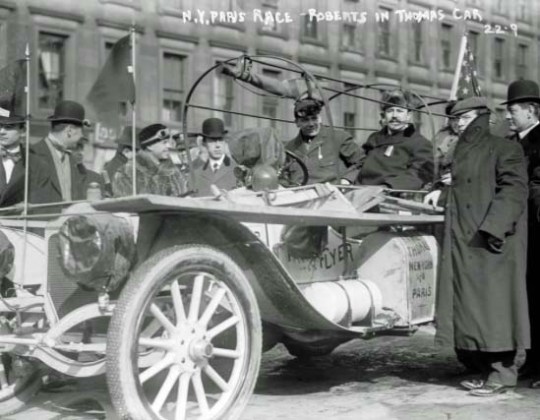

It was cold and windy in New York City on Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12, 1908. The quarter of a million people lined up along Broadway were bundled up in their warmest clothes as they waited anxiously for the starter’s gun that would kick off a 22,000-mile (35,405 kilometer) race over land and sea from New York to Paris. It was a challenge involving men and autos that had never been undertaken before— and still goes unmatched.

The route, as planned, would take drivers across the US, through Canada into Alaska, across the Bering Strait, over Siberia and then through Russia and Europe to Paris. By starting in February, the organizers hoped that the rivers and dog sled trails in Alaska as well as the Bering Strait would still be frozen so the racers could use them as roads.

The New York Times and the Paris newspaper Le Matin were sponsoring the race. The winner was to receive a 1400-pound trophy (not quite something for your mantle), and undying fame. Thirteen cars had been entered but only six made it to the starting line: three from France, one from Germany, one from Italy and one from the US. The US had come close to not having an entry at all. The pioneers of America’s nascent automobile industry didn’t think the race was doable. Or possibly they didn’t want to compete against the better-known European car makers and risk defeat. I suspect the latter.

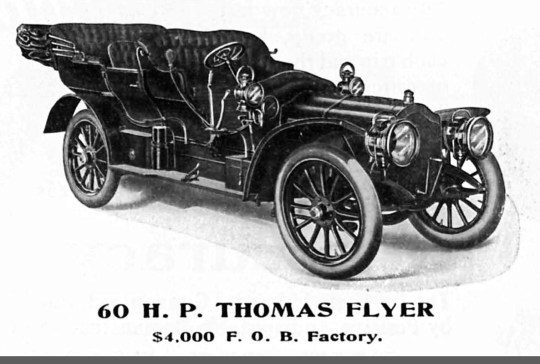

The ER Thomas Motor company out of Buffalo, NY came to the rescue a week before the event. It diverted a deluxe $4,000 Thomas Flyer that was meant to be sold in Boston. It was a stock, 60-horsepower touring car. Modifications were minimal. Three extra gas tanks were added to give the Flyer a capacity of 125 gallons. There would be no convenient gas stations along the way. You went to a hardware store, filled a bucket up from a metal barrel and poured it into your tank— if you could find gas.

Holes were cut in the floorboards to allow heat from the engine to provide some warmth. Long boards were attached to the side to aid in getting the car out of snow and mud. A covered wagon-like top had been jury-rigged to fit over the top and provide protection from snow, hail and rain. It was soon abandoned— full speed ahead and damn the weather! The Flyer, like all of the other vehicles was loaded down with chains, ropes, spare parts and tools. Each vehicle would travel with its own mechanic.

Thomas called his lead mechanic and road tester, George Schuster, the day before the race and asked him to go along. George knew how to handle adversity. He had been raised in a family with 21 kids. More to the point, he could fix almost anything on the spot, an early day Macgyver. Still, it’s hard to fathom being asked to participate in such an epic event less than 24-hours before it starts. It takes me that long to prepare for a weekend get-a-way!

Here’s how I imagine the phone call going:

“Um, Hi George, this is ER, can you spare a moment?”

“Sure Boss, what’s up?”

“I know this is short notice but could you show up in New York City tomorrow morning and go along on this 22,000-mile automobile race between New York and Paris? It shouldn’t take much more than six months but it’s going to be a tough trip. No one has ever driven across the US in winter. Heck, only 12 people have driven across it in summer. Who knows what the conditions will be like in Alaska and Siberia? You might want to carry a gun. One thing is for sure, there aren’t many paved roads and, in some areas, there won’t be any roads at all— or maps. You may have to drive down the railroad tracks or follow pioneer trails. I expect there will be lots of breakdowns for you to fix. We’ve even scheduled from eight p.m. to midnight each night for you to work on the Flyer and get it ready for the next day. It starts at five. Oh, and one more thing, I’ve asked Monty Roberts to drive. You know Monty, he’s something of a media hound and will take all of the credit but I am sure he will appreciate your ability to keep the car running. My love to your wife and kids. See you tomorrow.”

The European entries included a De Dion, Moto-Bloc, and Sizaire-Naudin from France. Germany was represented by a Protos and Italy by a Zust. If these names sound unfamiliar to you, it’s because none of them are around today, nor have they been for decades. Their builders had only been in the automobile business for a few years and horses were still considered a more reliable means of travel. The cars were assembled the old-fashioned way, by hand, piece by piece. Henry Ford had yet to invent the assembly line.

Considerable national pride was involved in the race. For example, 600 workers had been pulled together to work on the German Protos under the encouragement of Kaiser Wilhelm II. There was nothing stock about the vehicle. The Kaiser wanted to win for the greater glory of Germany and to promote German industry. I read in one account that Teddy Roosevelt, who was President at the time, also pressured American automobile manufacturers to participate. It’s hard to imagine a race starting in New York and crossing the country without US participation. Given Roosevelt’s personality, he probably would have been ‘biting at the bit’ to drive had he not been President.

As you might imagine, an international cast of characters and adventurers had assembled to drive and maintain the vehicles. I’ve already introduced Roberts who was in it for the fame. But he was also one of the few Americans who had actually trained for the 13-year-old sport of auto racing. The driver of the French Moto-Bloc, Charles Godard, had participated in the similar but considerably shorter Peking to Paris race the year before. It had been the first time he had ever driven a car. The driver of the German Protos seemed a bit more prosaic to me. Hans Koeppen was an aristocratic lieutenant in the German Army who hoped his participation would bag him a promotion to captain.

Antonio Scarfoglio, a 21-year-old Italian poet and journalist, was part of the Zust team. His father, a prominent Italian newspaper editor, had refused to let him go until Antonio had threatened to take a motorboat across the Atlantic, a much more dangerous adventure. The driver of the French De Dion, G. Bourcier de St. Chaffray, knew a bit about just how dangerous. He had once organized a motorboat race from Marseille to Algiers where every boat sank. The captain of his team, the Norwegian Hans Hendrick, had been more successful at sea. His claim to fame was having piloted a Viking boat to the North Pole. Solo.

The drivers were lined up and eager to go at 11:00 AM. George B. McClellan Jr., son of the prominent Civil War general and then mayor of NYC had been given the honor of starting the race. But he was late. The Mayor was rarely on time. At 11:15, Colgate Hoyt, a railroad financier, grabbed the gold-plated gun and shot it into the air. The race was on!

NEXT POST: The race across America.

Is this the race the movie, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” was based on?

No, G, but as Ray mentioned, It was the inspiration for the movie, “The Great Race.” –Curt

Alie will occasionally put “The Great Race” with Tony Curtis, Jack Lemon, Natalie Wood, Peter Falk and Kennan Wynn on TV, so I have seen it several times. But I had no idea there really was a New York to Paris race.

I haven’t seen the movie, Ray, and I really have to get it! Thanks for you and Alie reminding me. But I will bet one thing, no movie can capture the reality of the race! –Curt

I had no idea about this race. It sounds like pure madness. As we have the possibility of snow in the forecast for the day after tomorrow, I’m thinking these vehicles may have had a few weather challenges. Wowza! Looking forward to the next chapters.

Wowza! is right, Sue. I was hooked on finding out more about the race the first time I heard about it. I whine excessively if I have to put on chains and will drive a thousand miles out of my way to avoid doing so. 🙂 –Curt

Really enjoyed this. When I read the title I thought ‘how hard can that be?’ pick the fastest boat, get on a ship cross the Atlantic and drive two hundred miles. It didn’t occur to me that they were going west!

It’s really epic, Andrew, as I hope to relate in my next couple of posts. Glad you are enjoying the tale. Thanks. –Curt

Imagine how numb your bum would be by Paris 😉

Yeah! Pretty sure the shocks weren’t all that good on those early automobiles. And the road conditions… Ouch, ouch, ouch! 🙂 Everything I’ve read about Schuster was he was exhausted by the time he got to Paris. I haven’t read anything about the condition of his bum, however! –Curt

Fascinating account, Curt, of when motoring was a real adventure – though your road trips do a good job of recapturing that early excitement.

Adventures don’t get much better than the Great Race, Dave. I am glad that mine aren’t quite as exciting. 🙂 Thanks. –Curt

You do go to some amazing places, and I’m sure we’d love that museum in Reno. Thanks for the updates. Glad you’re safely home. And I enjoyed the information you shared in this post. We’re headed to Gettysburg and the Eastern Shore. Surely something interesting will present itself worthy of a post or two! (You can count on it.)

The museum is really worth a trip. I’ve never been excited about automobiles but the old ones are real treasures, true works of art!

Gettysburg has one of the best national park museums I have ever seen! Be sure to include it in your visit. And the whole area is chockfull of history— grist for lots of posts! 🙂 Enjoy. And thanks. –Curt

This story may have been told many times, but I’ve never heard of it. I enjoyed the tale immensely; it’s sort of an automotive version of around the world in eighty days. It also reminded me of Paul Theroux’s book The Happy Isles of Oceania: Paddling the Pacific: an account of an eighteen month long kayaking trip through the Pacific Islands. Needless to say, there were occasional portages!

I’ll say this: I’d far rather follow this race than what happens at tracks today. My dad would follow it occasionally, but it didn’t take too many left turns for me to begin looking for something else to do, like laundry.

Until I came across a mural in Goldfield, Nevada a few years ago, Linda, I had never heard of it either. Then it seemed to show up on my radar several times: at the National Auto Museum in Reno, on a new mural in Tonopah and then, this summer on our route through Nebraska where it had followed the same route as the Pony Express, Oregon Trail and Lincoln Highway. It was a clear sign that I had to do a series on it! 🙂

Like you, regular auto racing has little allure for me, but this one is in a class by itself. –Curt

Hope you and Peggy are well and safe with the entire state seemingly afire. I woke to ghastly orange hued skies this morning though there doesn’t seem to be any nearby blazes threatening us… yet!

The grandkids, on the other hand, had to evacuate from Stayton with very little warning. We’re playing it safe with ‘ready bags’ prepared… just in case.

Definitely praying for rain. Not to mention the rain dances.

PS Enjoyed revisiting this great story for a bit of distraction.

Pretty much gave you our news above. Thanks for checking in Gunta. Peggy and I are planning to visit Florence next week, assuming fire conditions allow. I did notice that the weather folks are predicting rain there on Monday and Tuesday. Hopefully it will work its way up and down the coast.

Sorry about your grandkids. The are up there seems as bad, if not worse than here. Clackamas County is really being hit hard.

Glad you found a little relief in my Great Race piece. I am working on Post #2 now. –Curt