For years, this painting of a C-109 flying the Hump was hung in my father-in-law’s home. It reminded him of his experience in World War II of flying supplies from India to China across the Himalaya Mountains. The painting now hangs in our son Tony’s home.

This is part II of my story about when Peggy’s dad, John Dallen, was forced to bail out of his plane on a pitch black, stormy night into a Burma jungle while returning from a flight across the Himalayan Mountains during World War II.

On February 10, 1945, my wife Peggy’s dad, John Dallen, began an adventure that would become an important part of our family history. At the time, he was serving as a World War II pilot for the Army Air Corps, flying fuel, ordinance, and troops from India into China to support Chinese and American efforts in the war against Japan. His 15th mission across the Hump began as routine. It would end with him parachuting into a raging storm, a pitch-black night, and an unknown jungle as his plane crashed in a ball of flame.

The Mission:

The briefing that morning would have been straightforward: Fly 900 miles from his home base of Kurmitola, India (near what is now Dhaka, Bangladesh) to Chengdu, China, deliver several tons of airplane fuel, and fly back to Kurmitola. (The fuel was used to support B-29 bombers that were based in Chengdu.)

The Fine Print:

John would be flying a C-109 tanker, an airplane that had been converted from a B-24 bomber by removing all of its armaments and adding extra fuel tanks. John was an experienced B-24 pilot from his training and instructor time in the US. While the B-24 was never known for its ease of flying, the converted C-109 was even more difficult to fly, especially when loaded. Landing at high altitudes with a load of fuel, as he would be in Chengdu, was particularly dangerous.

He had never flown this particular C-109 or with any of his crew, which was normal when flying the Hump. His crew members on this flight included a co-pilot (Ronald D. Anderson), an engineer (James E. Hatley), and a radio operator (John D. Beach).

His route was known as one of the most difficult anywhere. He would be flying over trackless jungles in Burma and the rugged, uncharted Himalaya Mountains, the highest mountain range in the world.

The only thing predictable about the weather was that it was unpredictable. He could have a relatively uneventful flight, or it could be filled with storms, turbulence and winds well over 100 miles per hour. Regardless of what the weather would be, he was expected to fly through it. This was standard procedure for Hump pilots in 1944/45. He did know that he would be aided by a tailwind going over and would be fighting a headwind coming back.

The Flight:

Both the flight and landing at Hsinching airfield in Chengdu were uneventful, or at least uneventful from the perspective of a Hump pilot. They made it with minimal bad weather. The flight had taken 5 hours and used 1100 gallons of fuel. At 2:30 p.m. they were ready for their return flight to Kurmitola. Using a stick measurement, the engineer estimated that some 1700 gallons of fuel remained. John and operational staff at Hsinching determined that this would be adequate for the return flight.

It was one of those times when the fuel tanks should have been topped off. The headwinds were stronger than the predicted 60-70 mph. The trip back would take longer than expected. John climbed to 17,000 feet and flew the plane to conserve fuel. Eight hours later at 10:30 p.m., the plane was still 300 miles out from Kurmitola. The engineer reported that there would not be enough fuel to make it. John decided to make for the much nearer air base of Shamshernagar near Talagaon, India.

Dropping down to 13,000 feet, he immediately encountered a snowstorm with moderate to severe turbulence and light icing. While he had to fly by instrument, it wasn’t the snowstorm that created close to impossible flying conditions; it was the thunderstorm waiting on the other side. “It was the severest I ever encountered,” John stated in his official post accident report.

He was more descriptive in the oral history he would give to his granddaughter Jennifer 50 years later. “The plane was tossed from side to side and up and down. There was no way to control it.” Breaking out on the other side, the plane was hit by an “extremely violent jolt,” (probably a lightning strike) which apparently damaged the plane. “It started turning to the left in spite of full right rudder application.” There was more bad news.

His co-pilot reported that engine number one had shut down, apparently out of fuel. John immediately ordered cross fueling from the fullest tank. The engine sputtered back to life. The engineer reported that there was 80 gallons of fuel left, but all gauges were now showing empty. Other engines began to sputter in and out.

Surrounded by thunder and lightning, his plane circling to the left, and his gauges showing empty, John was out of options. He ordered his radio operator to send out a Mayday. They were going to bail out of the plane before it was too late. The engineer and radio operator jumped first, the co-pilot next, and John last.

They jumped into a pitch-black night, lit only by lighting. It was impossible to see what they were jumping into. Would it be a river filled with floodwaters from the raging storm? Would they crash into the jungle trees that were known to grow upwards to 150 feet? Would their parachutes get caught in the trees leaving them dangling a hundred feet above the ground in the dark night? Would the crew members land close to each other or be scattered miles apart across the jungle? Would they survive?

As John’s parachute snapped open and he began his descent into the darkness, the horizon was suddenly lit by a ball of fire as the plane crashed into the jungle. It had been close, too close.

NEXT BLOG: Landing in the jungle and walking out.

Unimaginable for a desk jockey like me. Yet, the storyteller makes it possible.

It’s like when fiction becomes reality, Bruce. Fortunately, it has a good ending. –Curt

Very interesting story. I am staying tuned for the rest!

Head hunters and man eating tigers. (grin)

I shudder as I think about them jumping into the unknown from such height. But it was the wiser decision . . .

What a story.! And after all that, a marriage of over 66 years. Amazing on all accounts.

It has certainly fascinated me, Gerard. I am only sorry that John has passed on. I suspect he would have had a great time helping write the story.

Curt

Remarkable memory of the details – details he probably lived through hundreds of times in his later years. I’m thrilled you’re relating John’s story to us, Curt, so many, especially in the CBI are lost forever. The media seemed to concentrate on the Marines in the Pacific or the ETO, even the Army was pretty much neglected in the home front newspapers. That canope of jungle, at night, during a storm – it’s incredible he EVER came out alive!

Yes it is, GP. I can’t begin to imagine what it might feel like to parachute into a jungle you can’t see without a clue where you might land.

I am lucky to have the letters that John wrote home immediately after the event, and his niece’s oral history.

Fortunately, I was able to retrieve the official 14 page post accident report that he, his co-pilot, engineer and radio operator did within days after they walked out of the jungle. (It arrived the day before I wrote the blog on the crash.)

Peggy’s brother-in-law has been helping with the research, as has our son Tony. Both have the military background plus our son Tony is a pilot. It has been an interesting and worthwhile project.

I must say that your blog, and Koji’s, have provided me with the inspiration to do the research and write the story.

Thanks,

Curt

You made my day by saying I had anything to do with your project – I’m honored. As far as Koji goes – I have no words to accurately explain my admiration for him. His personality reminds me a lot of my own father, Smitty – 2 extraordinary people!!

Now that you have the report – can we expect an extra post?

The critical details on the report were included in today’s blog. I figured people didn’t need to hear about rpm’s etc. There was quite some discussion on whether he should have put more gas in the plane, obviously, or tried to land sooner. In my next blog, I cover his walking out, which is apparently information the army wasn’t interested in. Fortunately, I have the letters John wrote to his wife and his oral history, plus the stories he told me… Curt

Those letters are a treasure we will all soon share, thanks to you. The Army should have been interested in those achievements for teaching purposes for the new pilots, [you would think].

Thanks GP. It’s quite the story. And while the flying is outside of my realm of experience, I’ve spent my whole life wandering in the wilderness, including jungles, so John will be moving into my territory. 🙂 –Curt

Curt, do you know how old John was when it happened?

Let’s see, he was born in 1916 so that would have made him 28. –Curt

Thank you. Btw, my father was born in 1912.

Yep, and mine in 1904. 🙂 He was around 39 when I came into being. (grin)

Eagerly awaiting the next installment!

Alison

Sort of left you hanging up in the air, eh Alison. 🙂 –Curt

heh heh. Very clever 😉

Indeed, the fuel supply logistics for the B-29s in Chengdu were extremely ugly. To find out that John was one of those tasked with that job is shocking to say the least…and in a B-24. By all accounts as you say, it was a mother to fly.

I am so glad you are publishing this series, Curt. WWII HAS faded from the minds of many Americans – some of your family’s too, I’m sure. We need folks like you to bring them back into the spotlight. Hell, can you imagine that spoiled brat Just Bieber being behind that stick…let alone bailing out into total darkness? John and his crew were a hundred times the man.

I’ve been planning to tell this story for quite some time, Koji, as you know. I am glad I finally got into it. The research has been fascinating. And I really appreciate having primary sources. Yes, the family is appreciating the story, Plus Peggy’s brother John and our son Tony have jumped in to help.

As I told GP, I credit him and you for inspiring me on this series. Thanks. –Curt

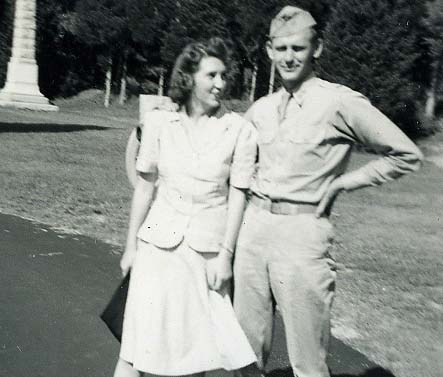

BTW, John’s first portrait as a 1st Lieutenant in the USAAF was dashing… yet his young face belies the horror he endured…and kept for the rest of his life. I, for one, appreciate his dedication to this country.

It is interesting to see the contrast on a photo I am posting of John right after he walked out from the crash. Hopefully the blog will go up today. –Curt

Trying to get there!!!

Finally finished. 🙂 I have it scheduled to go up tomorrow morning, Monday.

An exciting story! WWII made some very unique and strong men.

Yes it did Rebecca. And thanks. –Curt

Since I just saw the movie Unbroken I cannot help but think of it as I read about your father-in-law. The courage and ingeniosity of these young men were awesome. The photos are also beautiful. Love the face of John when he was a little boy. Thank you for sharing this family story, here on your blog, Curt.

My own appreciation for John, and all those that have faced what John did, has grown as I’ve researched and written the stories. Thanks, Evelyne. –Curt

Salutes from an ex-army officer of the Indian Army to the courageous handsome pilot!

And a wonderful New Year to you and yours 🙂

That’s neat. Thank you Dilip.–Curt

Compelling story. Looking forward to more of it…

Thanks Bill. With a little luck, it should be up today.

Talk about a cliff-hanger. You tell it well.

The tale deserves a story-tellers approach Hilary. –Curt

Very exciting, as was the first installment. I love this tale, Curt. Thank you for telling it. All of us who work at VA have a very big soft spot in our hearts for WWII vets.

Thanks Crystal. John, like his compatriots, was a special man. I’ve truly enjoyed writing about his experience. –Curt

Love your storytelling friend!~ Excellent…

Thanks Slingshot. Nice compliment coming from another writer. 🙂 –Curt

Thunder and lightning to boot. Too close….aye! Incredible.

The story captured me the first time I heard it, D. Thanks. –Curt

My cousin’s son is a Navy pilot – no longer flying off carriers, but teaching new pilots. I’ve had the chance to see the trainers, the tail hooks, the carriers.. . The thought of what these young men accomplish now, as they did then, is so inspirational.

Sometimes I worry that, if we are faced with a real challenge as a nation, we won’t be up to the task any longer. That’s one reason to publish stories like this — to remind people of what human beings are capable of.

A very good question Linda. Would we be up to the task? I like to believe that we would. I’ve seen our kids respond to similar challenges and succeed. For a number of years, I took people on nine-day, hundred mile backpack treks. Many people that went with me had never had such an experience. And it was tough. I was always amazed how they ‘rose to the occasion.’

Curt

My grandfather is Ronald Anderson, the co-pilot mentioned. He’s sick in the hospital now at 91 years old. I’ ve heard his story for years, and have a copy of the book he wrote 50 or so years ago. I’m praying he’ll be around a little longer. If you have any more info about that flight, I’d love to hear it, and so would my mother, his daughter.

Jeff

So glad you checked in Jeff. I think I included most of what I had from the various stories, certainly the essence of it. It was an amazing story.

I would love to get as copy of the book your dad wrote. Is it still floating around out there? Has Google reproduced it? Helen, John’s wife is still living in Sacramento at age 94 but her memory of the time has become somewhat limited. All of John’s three kids, including my wife, Peggy, are still alive and well. –Curt

Hi Curt,

Just doing a film of my mums childhood, and she mentions billeting these pilots in their home in India, She now lives in Melbourne (81) She remembers the pilots and

how it was dangerous to fly ‘The Hump’ into China- The Young American pilots, were very kind to her as a child and used to have Tootsie rolls (chocolate) in the fridge for her. (Wondered if I may use the picture for a few seconds in the film, which is not commercial?)

You’re welcome to contact me Simon Wrigley masterlight1@gmail.com

I can give you her phone number in Australia.

Good to hear your story that ended well!

Great story, Simon. Tootsie rolls were a thing of our childhood as well. Of course you are welcome to use whatever photos you want. –Curt

Amazing! I don’t think tales like this could ever happen again. Fighting is so different now. But thinking about fighter pilots and a war in the air seems so vivid and otherworldly. What a story!

I agree, modern communication systems and GPS would have guaranteed that John knew exactly where he was and allowed him to communicate that information immediately. Where he crashed probably has cell phone coverage now! Even backpackers can carry locator beams today in case of an emergency. Thanks. –Curt

Reblogged this on The Java Gold's Blog.

wow, how interesting story, Curt… oh, on his picture as First Lieutenant, he looks like handsome Henry Fonda… 🙂

I am sure John would smile at the “handsome Henry Fonda” comment, Melanie. His daughter (Peggy) did. –Curt

When you left country after your tour of duty was over in the CBI what route back to the States did you take?

My father-in-law flew to the west coast of India and then travelled by troop transport back to the US, Ronald. –Curt