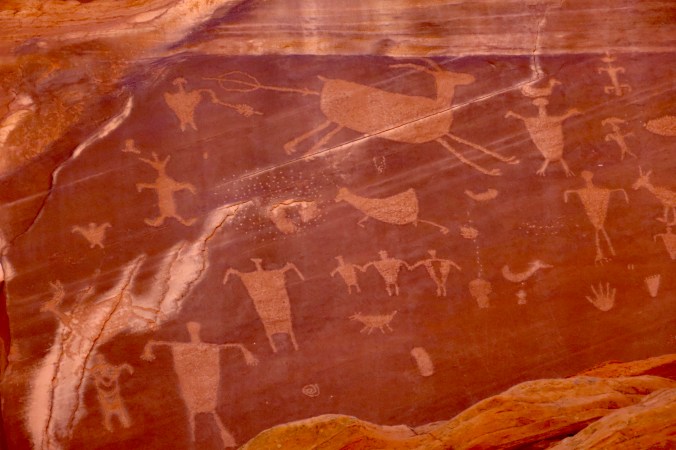

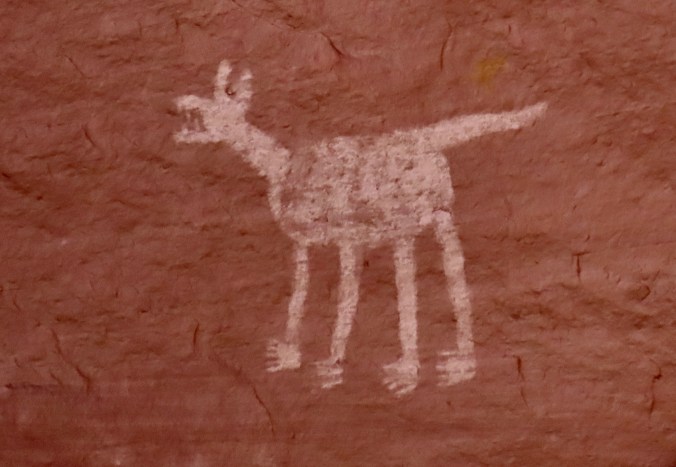

Peggy found several petroglyphs she might include in her next word search book— but don’t expect to find the naked couple.

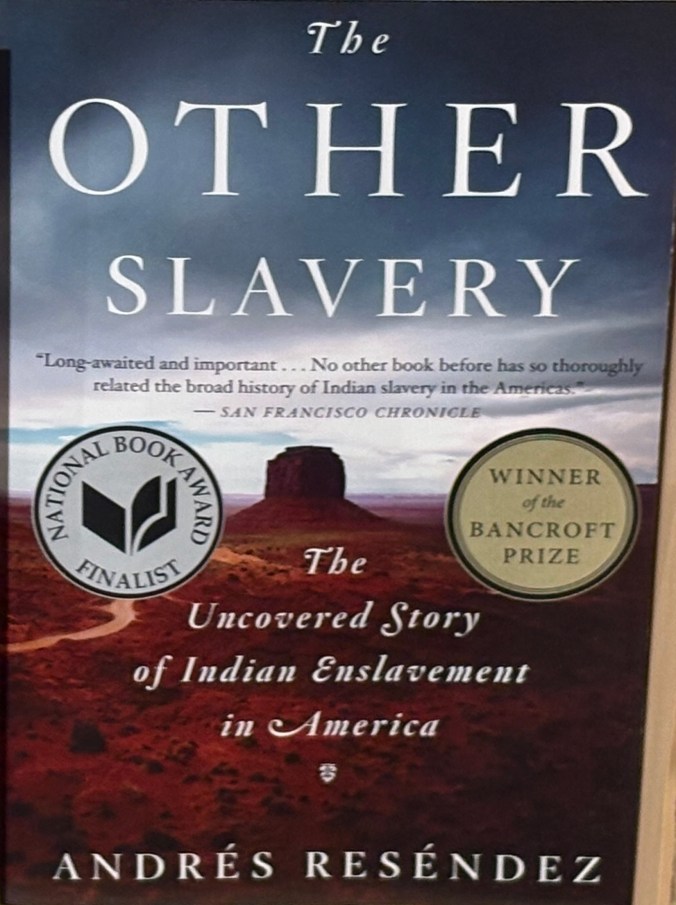

The occupation by the Navajo has been interrupted twice. In 1805, Spanish forces under Antonio Narbona, the future governor of Spain’s New Mexico territory, attacked, killed and captured a number of Navajos because they refused to accept Spanish rule.

By the 1860s, the Navajo faced a new threat. American settlers from the eastern US were pouring into the newly acquired territory and the US Government developed a policy to make room for them by ousting the natives. The Navajos would be required to move to reservations, leaving their homelands behind for the newcomers. Not surprising, they refused. So a decision was made to force them out. The US Army under the command of James Henry Carleton ordered Kit Carson to subjugate the Navajo using a scorched earth approach that involved burning their homes, destroying their crops and killing their livestock.

Earlier, in his efforts to subdue the Mescalero Apaches, Carleton had given the following order to his subordinates: “All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you can find them. … If the Indians send in a flag of truce say to the bearer … that you have been sent to punish them for their treachery and their crimes. That you have no power to make peace, that you are there to kill them wherever you can find them”.

In 1864, facing starvation, the Navajo capitulated, signed a treaty, and began a forced march during the heart of winter to Fort Sumner’s Bosque Redondo Reservation in New Mexico. The 300 plus mile hike, the Long Walk as it came to be known by the Navajos, left numerous Navajo dead from exposure, starvation, and exhaustion. Bosque Redondo was equally bad if not worse. Food, space, water and sanitation facilities were limited in the extreme for the 8500 Navajo and 500 Mescalero Apache occupants. Furthermore, it was run like an internment camp instead of a reservation. An estimated one quarter of the population died during the four years of the camp’s occupation.

Finally, in 1868, a new treaty was signed with the Navajo that allowed them to return to a portion of their original homelands, including Canyon de Chelly. Today, the Long Walk, like the Cherokee’s Trail of Tears, is remembered by the Navajo an an important part of their history.

it isn’t a history that the Trump Administration wants remembered however. He has ordered the Department of the Interior to take action to ensure “descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living (meaning information like that above), and instead focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people.

Apparently, Carleton and Carson are not to be disparaged. My bad. History is to be remembered as Trump wants it remembered. George Orwell’s 1984 comes to mind.

Today, marks the end of my planned series on the Trump Administration’s threat to our national parks, monuments and other public lands. I believe that I have covered his primary focus and actions as they relate to our public lands. Having said that, I’ll still report on major threats as they emerge and, at some point, do a summary of how successful efforts to protect the parks have been.

I also have in mind doing a post on Mt. Rushmore National Monument. The President has repeatedly expressed a desire to have his image added to those of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. (At one point, Elon Musk even volunteered to carve it, but I suspect that’s off the table.) My objective is to look at the major accomplishments of each of these men who played such an important role in making the nation what it is today and then comment on how the President goal of Making America Great Again, relates to their accomplishments.

But for now, it’s back to sharing the beautiful and fascinating world we live in while Peggy and I continue to ‘wander through time and place.’

For those of you who keep track, Peggy and I are now back at our home/basecamp in Virginia. We still have several blogs from our journey into the Southwest that I will be posting over the next several weeks as we get ready for another adventure: Leaf peeping in New England, along the Blue Ridge Highway, and at Great Smoky National Park.

I’ve have been to Albuquerque, New Mexico several times over the years. One place that I always wanted to go but never managed to was the American International Rattlesnake Museum. They have one of the largest collections of live rattlesnakes in the world. Could it be that whoever I was traveling with didn’t share my enthusiasm?

Peggy, however, is game for almost anything and snake images almost always show up among the petroglyphs that fascinate her so much. So off we went to the museum two weeks ago.

That I have a certain ‘fondness’ for rattlesnakes isn’t news to my blog followers. I’ve had numerous encounters with them over the years and have written about several. I’ve even been known to get down on my stomach when they are crawling toward me so I can get better head shots. (Peggy gets a little ouchy about that.) I suspect my attitude would be considerably different if I’d ever been bitten by one. Rattlesnake bites can be deadly, or at a minimum, extremely painful. It’s not something one wants to test.

Fortunately, rattlesnakes come with an early warning system. They rattle. The rattles are made up of keratin, that’s the same thing your fingernails are made of. When irritated, the snake vibrates its tail, knocking its rattles together. It makes a very distinctive sound, one you never forget, one guaranteed to shoot your heart rate up faster that a skyrocket on the 4th of July.

A rattlesnake you see coiled up, rattling its tail, and ready to strike is worrisome, to put it mildly. It’s not a problem, however— as long as you stay clear of its strike zone, which can range from half to two thirds of its body length. For a six foot snake (which is a very big snake), that would be from 3 to 4 feet. If you want to check this out, use a long stick. I have. (Don’t try this at home, kids.)

One you can hear but can’t see is a quantum leap scarier. I stepped on a dead log once ‘that started to rattle’ and found myself an olympic winning 15 feet down the trail before my mind registered snake. There is some evidence that our fear of snakes is instinctive. For example, have you ever come close to stepping on one you didn’t see in advance. Did you find yourself thinking, “snake, maybe I should be concerned.”

When I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in West Africa, I had a cat named Rasputin that proved the hypothesis about fear of snakes. I discovered if I took the old fashioned spring off my back door and rolled it toward him, he would leap 6 feet into the air and land on our couch or other piece of furniture well out of reach from the deadly ’snake.’ Being scientifically oriented, I did it 3 or 4 times just to make sure.

On the other hand, back in California I had a basset hound named Socrates that seemed to counter the theory. I was hiking with him one day at Folsom Lake near Sacramento when I noticed him walk out on to a granite ledge and start sniffing down into the cracks. Suddenly he began barking like the baying hound he was: Loud. Simultaneously, the rock became alive with rattles. Socrates had discovered a rattlesnake den. They can get big, big like in a hundred snakes. Some have even been found with a thousand. Talk about an Indiana Jones’ nightmare…

It was for me, as well. “Socrates, come here!” I demanded. And then again. And again. Each time louder and more desperate. All, to no avail. He just kept barking louder. Damn, that dog could be stubborn. Finally, there was nothing I could do but walk out on the buzzing rock, grab him by the collar, and bodily drag him off. I was lucky I didn’t pee my pants. Had I not immediately put his leash on and pulled him away, he would have gone right back to barking up a storm at the irritated, poisonous serpents.

Here are a few facts on rattlers:

And now for a few of the photos we took at the museum.

Plus a couple of snakes that weren’t rattlers, but we were fascinated by their colors.

Peggy and I have visited Canyon de Chelly twice, first in 2019 in October and then this year in June. In 2019 we drove the South and North Rim roads and then explored the inner canyon. The two roads are open for anyone to drive. The tour of the inner canyon requires that visitors have a Navajo Guide along. Our friends Tom and Lita from Sacramento joined us in June where we did the inner canyon tour but, unfortunately, didn’t have time for the rim drives. I’ve opted to use photos from both visits.

We are going to feature the scenic side of the canyon today. Next week, we will look at the canyon’s ancient history in terms of pueblos that the Ancestral Puebloans built in the canyon and petroglyphs and pictographs from both the Puebloan and Navajo time periods. I also want to discuss the Long Walk where Navajo were forced to abandon their homelands to settlers pouring in from the eastern US. It’s the type of story that President Trump is now trying to ban from national parks and monuments because it detracts from his concept of a great America.

But first, the beauty.

As part of our series about protecting national parks, monuments and other public lands, I’ve been reading news releases from the directors appointed by President Trump who oversee these areas. It’s not a task I would wish on anyone. It isn’t surprising that the directors all support the president’s objective of significantly reducing many public lands in size and opening up others for profit making operations. That’s why they were appointed.

The news releases are full of statements designed to hide their real purpose. Here’s an example:

“President Trump promised to break the permitting logjam, and he is delivering,” said Energy Secretary Chris Wright. “America can and will build big things again, but we must cut the red tape that has brought American energy innovation to a standstill and end this era of permitting paralysis. These reforms replace outdated rules with clear deadlines, restore agency authority, and put us back on the path to energy dominance, job creation, and commonsense action. Build, baby, build!”

Let’s did a little deeper. By ‘permitting logjam’ and ‘red tape’ and ‘outdated rules,’ he means rules that have been developed to protect our air and water quality, save rare and endangered species from extinction, and maintain areas of great beauty and/or cultural significance that the majority of Americans support protecting. The Administration’s perspective is that these rules get in the way of progress. Who needs clean air or water. “Build, baby, build!”

And how about American energy innovation and dominance? Obviously, he’s not talking about solar, wind and water power. We’ve been moving ahead quickly in the development of clean energy. The Trump Administration is actively discouraging this progress. Incentives designed to encourage their use have been cut. His passion is for coal, gas and oil, all three of which are nonrenewable resources and have been prime factors in the development of global warming that has been having such devastating impacts on the US and the world. The Texas floods of this past week are but one of a multitude of examples.

Several countries in the world have now reached the point where 80-100% of their energy needs are supplied by renewable clean energy. I’d argue that they are the ones achieving energy dominance, one that will last long beyond our nonrenewable resources and is vital to our battle against global warming.

On another subject, it’s interesting that right-wing Republicans played an important role in blocking the administration’s plans to sell off millions of acres of public lands in the West. Here’s what Christopher Rufo, a culture warrior and leading supporter of Trump in in the state of Washington had to say:

“Pre-2016, you’d have the small government argument against a kind of federal domination over the land, but Trump and MAGA is a nationalist movement,” he said. “I think many conservatives are now reassessing these questions, and many of us in the West understand that part of a great nation is the preservation of its natural beauty.” There is hope.

The Marble Mountain Wilderness, the subject of this post, is an example of this beauty.

This post is part of Peggy and my series on national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands with an emphasis on their unique beauty, geology, flora, fauna and history that makes them so important to us today— and to our children, grandchildren and future generations.

There are a couple of interesting developments in the Trump Administration’s efforts to sell off public lands and post signs at national parks urging visitors to report on any negative historical signs or comments about the past. An example of the latter would be the forced removal of Native Americans from their homelands to make space for settlers from the East.

The Sierra Club reports that the plan to sell off public lands was stripped from the Administration’s ‘Big Beautiful, Mega-Deficit Bill’ in the Senate. This doesn’t mean that the Administration won’t move ahead in selling lands by claiming it doesn’t need permission from Congress.

As for public comments generated so far by the signs, an analysis done by the National Parks Conservation Association and summarized in the Washington Post shows strong support for the parks:

“The comments overwhelmingly praise the parks as beautiful national treasures, with dozens complimenting rangers for their knowledge and navigational help. Many called for undoing funding cuts and rehiring staff who were fired by the Trump administration.”

On the other hand, some felt that there were too many mosquitoes and not enough moose.

I think the message to the Administration might be “to watch what you ask for.” Whether the Administration chooses to report on the responses, select out the ones that support its policy, or simply bury the results, is another issue. I seriously doubt that it will report on the overwhelming support Americans show for national parks and other public lands.

Peggy and I often get a question about where we are now, given that we wander a lot and our blogs may reflect a recent adventure or be back in time. Right now we are in Safety Harbor, Florida. Peggy and I flew out here from Sacramento to celebrate Peggy’s 75th Birthday with our son, Tony his wife, Cammie, their three sons: Connor, Chris and Cooper, plus…

Today, Peggy and I are continuing our series on national parks, monuments, wilderness areas and other public lands with an emphasis on their unique beauty, geology, flora, fauna and history that makes them so important to us today— and to our children, grandchildren and future generations. I can only repeat how vital it is at this point in history to let decision makers know how we feel about protecting and maintaining public lands.

In my last post, I discussed a bill by Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah to be included in President Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” that would require the government to sell of 50-75% of BLM and National Forest Lands in America over the next five years. Here’s what the Southern Utah Wilderness Association has to say about the bill:

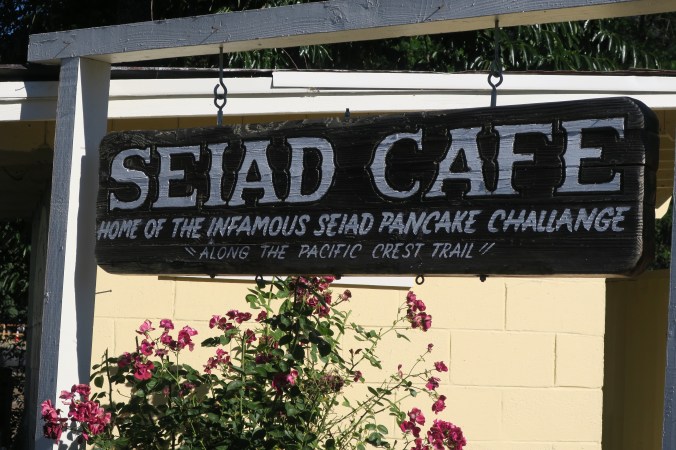

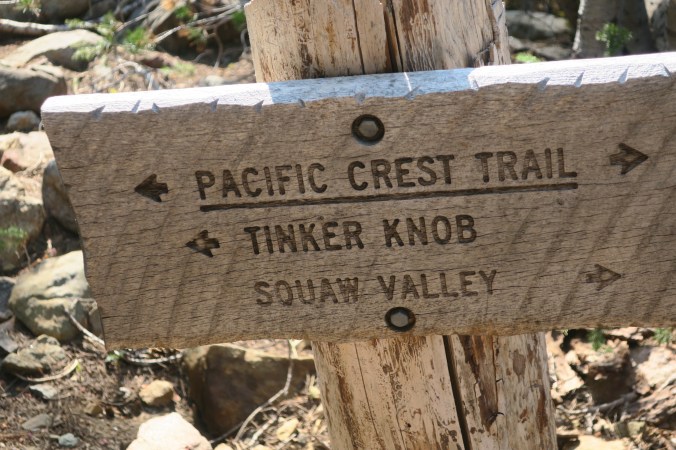

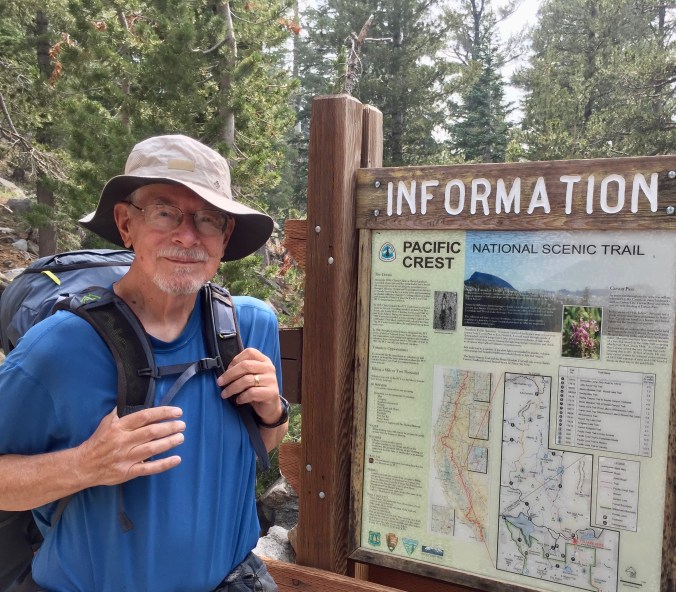

The Pacific Crest Trail Association also noted this week that the bill would have serious implications for the PCT by blocking access to the public lands that the trail now crosses over. The 750 mile trip I did for my 75th birthday would not be possible. But that’s nothing compared to the millions upon millions of people who would forever lose future access to these lands that now belong to all of us. Please, let your Senator know Lee’s bill will do irreparable damage.

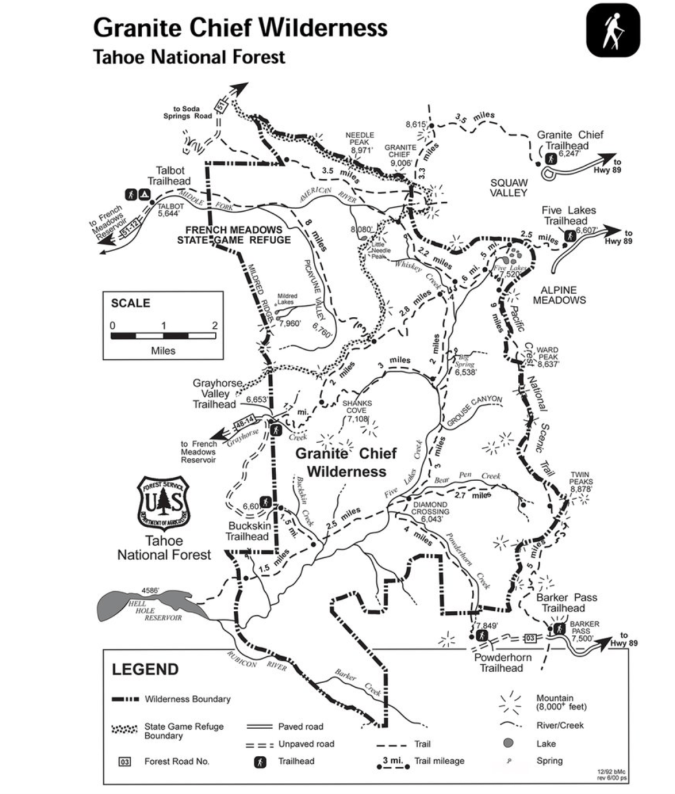

But, now on to my post about hiking through the Granite Chief Wilderness on the Pacific Crest Trail.

“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.” John Muir

The Wilderness Act of 1964

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” –Howard Zahniser, Author of the Wilderness Act

What does this mean? Transportation is by foot or horse. No bicycles or motor vehicles are allowed. Even chainsaws are banned for use on trail maintenance. No one can build permanent structures of any type. It’s just you and nature.

As of 2023, there were 806 wilderness areas located in 44 states and Puerto Rico. These areas are overseen by the National Park Service, the US Forest Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the US Bureau of Land Management. All in all, some 5% of land in the US is set aside as wilderness area, the majority in Alaska.

Over the past three months, I’ve been blogging (with Peggy’s help) about our national parks and monuments with an emphasis on their unique beauty, geology, flora, fauna and history that makes them so important to us— and about the threats that they are presently facing from the Trump Administration. Today we are switching to wilderness areas with the same emphasis. I’m going to cover three that I backpacked through on my 750 mile trip down the PCT in 2018 to celebrate my 75th birthday: The Mokelumne, Granite Chief/Desolation, and Marble Mountains Wilderness areas. If you’ve been with this blog for a while, some of the photos may be familiar to you.

The Mokelumne Wilderness is conveniently located between two of California’s highways that cross the Sierras. Since I was hiking north to south, I started at Carson Pass (elevation 8573’) on Highway 88 and ended at Ebbet’s Pass (elevation 8732’) on Highway 4. The distance on the PCT is approximately 30 miles, which is relatively short— but there are plenty of ups and downs! And, as you will see, great diversity and beauty.

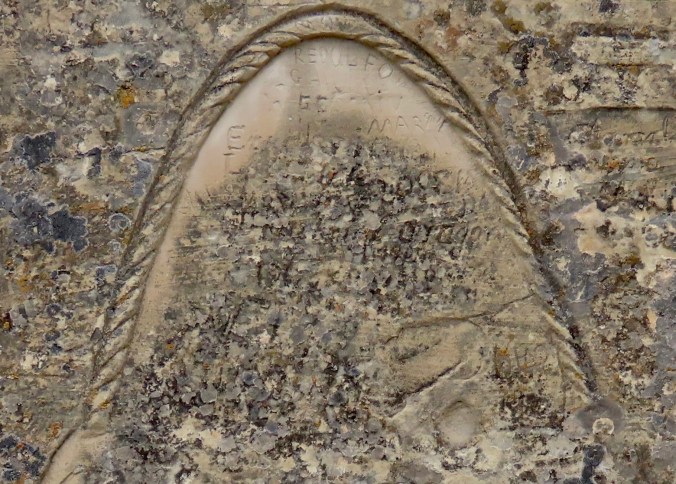

Peggy and I were admiring the petroglyphs and signatures on the walls of El Morro when a woman walked by and gushed, “Aren’t the signatures wonderful.” And then, dismissively, “You can find petroglyphs anywhere.” We didn’t disagree on the signatures. The first one had been carved into the rock by the Spaniard Don Juan de Oñate, 15 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. But the petroglyphs reflect the life of a people who were living here hundreds of years before Oñate was born.

While our understanding of the petroglyphs is limited, we can appreciate the creativity and at least guess at their meanings. The four big horned sheep walking in a row on the Inscription Loop Trail are still four big horned sheep walking in a row, regardless of what else the petroglyph might mean. With insights from the beliefs, legends, and interpretations of modern pueblo people and other indigenous groups, our guessing can improve, opening a whole new world of wonder for us. They certainly have for Peggy and me.

The pueblo, signatures, and petroglyphs are part of the rich history that our public lands preserve and protect. It’s an important aspect of what our national parks and monuments do. Without this protection in El Morro, graffiti would likely cover the inscriptions and petroglyphs on the Inscription Loop Trail, while much of the Atsinna Pueblo would be dug up with zero concern for history— left in shambles as treasure hunters search for ancient artifacts to sell. Before the creation of our park system, such pillage was common. It still can be in unprotected areas.

Today we are facing an even more insidious threat: erasing our history. Apparently, the Trump Administration has decided that including what we have done wrong in history detracts from America’s greatness rather than serving to remind us that we can do better. For example, my Great Grandfather in Illinois utilized his house as a part of the Underground Railroad. It was dangerous. He was helping free slaves. In early April, a page on a national park website described the effort this way: “The Underground Railroad — the resistance to enslavement through escape and flight through the end of the Civil War — refers to the efforts of enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom by escaping bondage,” the page began. The statement was removed as well as a photo of Harriet Tubman, who was central to the effort. The Underground Railroad became part of the Civil Rights movement. There was to be no mention of slavery. After a sustained outcry and substantial media attention, slavery and Harriet Tubman were returned to being part of our history.

It continues. Two weeks ago, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum issued Secretarial Order 3431 that instructs all land management agencies, including the National Park Service, to post signs asking visitors to report any negative stories about past or living Americans by rangers or in signage— even if it is historically accurate.

Rewriting history to match the President’s concept of it and asking Americans to spy on Americans is a whole new type of scary.

And now, it’s time to return to our post on El Morro National Monument, which is part of our series emphasizing the beauty and value of our national parks, monuments, historical sites and other public lands.

I joked with the park rangers when we came back to see Atsinna about using the Ancestral Puebloan route up. He laughed, “I’d recommend the stairs. There are 130 of them.” “Piece of cake,” had been my response. “Actually,” he amended, “there are 132.” “Oh no!” I whined.

Next up I am going to explore three wilderness areas in California as part of my series: The Mokelumne, Granite Chief/Desolation, and Marble Mountains Wilderness areas. While these wilderness areas are not presently threatened by Trump Administration policies, there is no guarantee that they won’t be.

Ancestral Puebloans— whose descendants include modern day Zuni— came first. They lived on the top of El Morro in a pueblo that the Zuni have named Atsinna, and climbed down to the waterhole where they gathered water and used rocks to pound and carve petroglyphs into the relatively soft Zuni sandstone.

The Puebloans were followed by Spanish treasure hunters driven by an insatiable hunger for fabulous wealth and everlasting glory. They believed they would find it in the legendary, gold-filled Seven Cities of Cibola. (El Morro is in modern day Cibola County.)The treasure hunters were accompanied by Spanish missionaries with a different goal: Winning souls for God and King. Turns out the the cities of gold were a myth and the indigenous population didn’t understand why they couldn’t keep their own deities while accepting God’s help as well. They were even more dubious about a distant king whose motives were questionable at best.

Finally, American pioneers and soldiers passed through in the mid-1800s. The pioneers were seeking a new life from the one they had left behind in the East. They, too, were searching for treasure but theirs was to be found as farmers, ranchers, miners, loggers and merchants. The fact that indigenous populations already lived in the areas they wanted to settle was of little concern, unless, of course, the natives objected. That’s what soldiers were for.

The Spaniards and Americans, like the Puebloans, left their marks on the cliff, but this time they signed with their signatures using chisels and knives. One of the primary reasons people visit El Morro is because of the various signatures and petroglyphs. There are over two thousand. Some, like Peggy and me, also come because of the beauty and culture.

Because of the length of this post, I’ve decided to break it into Part 1 and Part 2. The first part will emphasize the area’s beauty and the early visits by Spaniard treasure hunters and American pioneers between the 15th and 18th centuries. In the second part, Peggy and I will focus on the Ancestral Puebloans from the 11th century.

Today, Peggy and I are continuing our series on national parks, monuments, and wilderness areas with an emphasis on their unique beauty, geology, flora, fauna and history that makes them so important to us today— and to our children, grandchildren and future generations. I can only repeat how vital it is at this point in history to let decision makers know how we feel about protecting and maintaining public lands. It makes a difference.

For example, the Trump Administration’s provisions for selling off public lands and building a mining road through the Gates of Arctic National Park in Alaska were both removed by Republicans from his “Big, Beautiful, Bill” last week for FY 25/26. Once gone, the public lands (that belong to all of us) would be gone forever. As for Gates of the Arctic, it is one of the world’s largest remaining roadless and trail-less wilderness areas. A road through the heart of it would change its pristine nature significantly and open up other National Parks for similar treatment.

As with each of our previous posts in this series, we will present photos that focus on the beauty and unique characteristics of the park, monument, or wilderness we are blogging about. All photos have been taken by either Peggy or me unless otherwise noted.

Now, please join us as we explore El Morro.