This tunnel of cypress trees leading into the Marconi-RCA wireless receiving station at Point Reyes National Seashore in California is considered one of the most beautiful tree tunnels in the world.

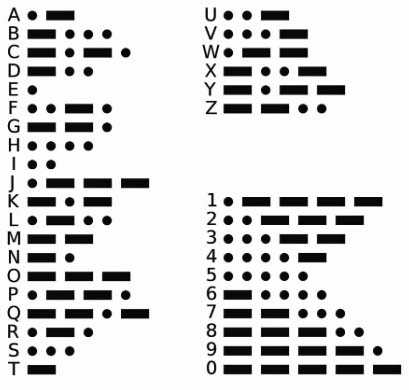

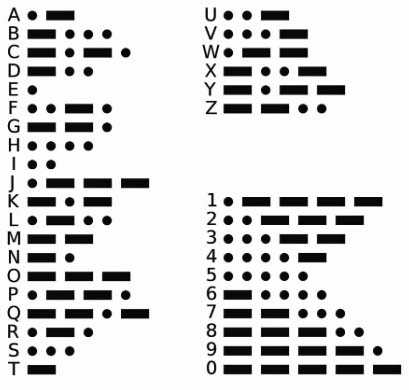

Do you recognize the dits and dahs? I memorized what they meant for a Boy Scout badge back in the Dark Ages, back before satellites and modern communication systems came to connect almost anyone, anywhere, anytime. Here’s a clue: the three dots stands for S, and the three dashes for O. Think SOS: Save Our Ship. You will recognize the whole alphabet spelled out in dits and dahs as Morse Code, named after the American inventor Samuel Morse, who developed it in 1838.

Morse Code

Combined with telegraph lines and operators, it revolutionized communication. Getting the quickest message between points A and B no longer required finding the fastest horse or train. Seconds instead of days or weeks became the rule for sending important communications over long distances.

What Morse did for land based communication, Guglielmo Marconi did for oceans. His claim to fame was being the prime inventor of wireless communication using radio waves. He started at the young age of 21, working in his attic in Italy with his butler Mignani. (I am reminded of the young Steve Jobs, sans butler, working out of his garage in Palo Alto.) Like Jobs, Marconi was an entrepreneurial genius as well as an electronics wizard, or geek, if you prefer. He began by sending a message across his attic in 1894 to ring a bell. By 1902, he’d cornered the market on sending wireless messages using Morse Code across the Atlantic Ocean.

Ships at sea and their passengers were among the primary beneficiaries of the new technology. “Surprise, you are a new father. Send money,” could now be transmitted immediately instead of weeks down the line. There was also a safety factor. For the iceberg bound Titanic, it meant that 30% of its passengers were saved— instead of none.

By 1914, Marconi had extended his operation to the Pacific Ocean and built sending and receiving stations in the Marin County towns of Bolinas and Marshall north of San Francisco. (Because of interference, sending and receiving stations had to be separated.) During and immediately after World War I, military concerns combined with a touch of nationalism, and, I suspect, a generous dollop of old-fashioned greed, led to the take over of Marconi’s American operation and its transformation into RCA, the Radio Corporation of America.

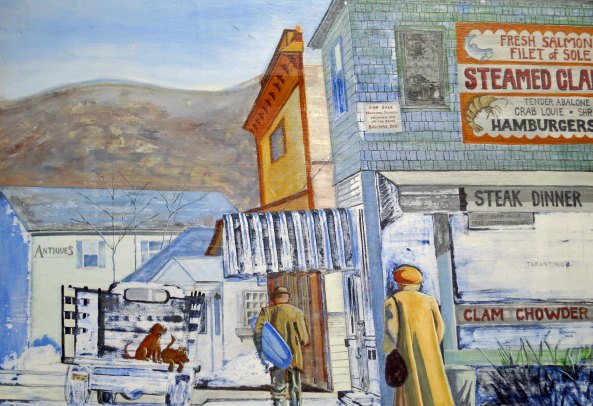

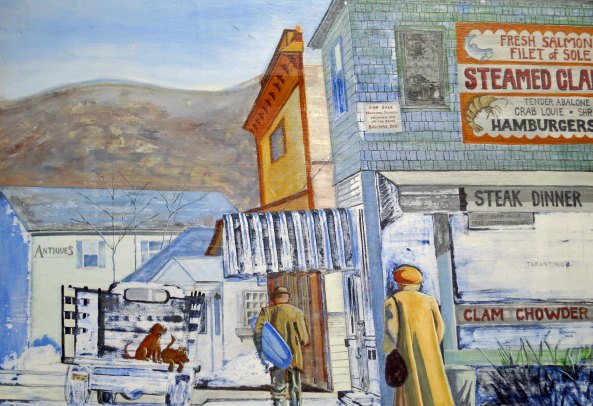

A mural in Olema, California just north of San Francisco that provides a look at what the community looked like when it served as the Pacific Ocean telegraph sending station for Marconi-RCA telegraph. The blue surfboard represents a bit of artist creativity. (grin)

An early photo of the Marconi receiving site in the small town of Marshall on Tomales Bay. Workers lived in the hotel.

The hotel as it looks today as part of the Marconi Conference Center.

Old Highway 57, the dirt road, once serviced the Marshall Marconi wireless receiving site. Modern Highway 1 is seen below along with Tomales Bay. The distant hills are part of Point Reyes National Seashore.

Historic Marshall included this old/now deserted seafood restaurant built in 1873.

Today, Marshall is known for its oysters and kayak eco-tours.

I found this old rocking chair sitting along Highway 1. All it needed was an old codger to sit in it.

In 1929, the Marshall operation was moved to Point Reyes. It was still there actively receiving messages when I first started visiting the National Seashore in the late 60s and early 70s. A forest of receiving antennas and no trespassing signs announced its presence. Most of the communication with American ships involved in the Vietnam War passed through the facility. On July 12, 1999, the station sent its last message. Dits and dahs had been made obsolete by bits and bytes.

I was drawn there on my August trip up the North Coast of California by a statement I had found on the Net stating that the cypress trees at the entrance formed one of the most beautiful tree tunnels in the world. Even though I had driven by the facility dozens of times over the years, I had never noticed. Shame on me. When I drove up, a group of amateur photographers with expensive cameras were busily proving the point. I joined the queue with my small Cannon S-100.

I was also blessed with a touch of serendipity. A display sign announced that the Maritime Radio Historical Society was featuring a display on telegraph use in Marconi’s impressive Art Deco headquarters. I drove down under the tunnel of trees and walked through the building’s open door. An hour later I emerged with the distinctive sound of a telegraph keys clattering away in my ears and enough information for a dozen blogs.

The lovely art deco building was built by Marconi-RCA for its telegraph receiving station at Point Reyes National Seashore.

Steven King, a volunteer with the Maritime Historical Radio Society and the Point Reyes National Seashore spent most of an hour explaining how the Marconi-RCA wireless receiving station worked during its heyday.

Every ship at sea had its own call sign for receiving telegraphs. These were left when the last telegraphs were sent out in 1999.

A view of the telegraph receiving antennas as they look today.

I had a final opportunity to drive under the beautiful bower of trees as I returned to the highway.

NEXT BLOG: I head north for the small town of Bodega to explore where Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Birds was filmed and discover a church that was photographed by Ansel Adams.