Since I am telling family ghost stories this week, I am going to relate a ghostly encounter that Peggy and I had in Scotland last year.

It has to do with my search for the grave of John Brown, the Martyr of Priesthill.

I first heard of Brown in the late 60s when my dad arrived home from a Mekemson family reunion. He proudly produced a family tree that traced a branch of the Mekemsons back to the martyr. Given the staunch Presbyterian leanings of our ancestors, it was an important connection.

My Great, Great, Great Grand Father, James Mekemson, married Mary Brown Laughhead Findlay. (Mary had already seen two husbands die.) John Brown was five generations up the line.

The story of John Brown’s murder verges on legend. He was, as the saying goes, a Covenanter’s Covenanter, a very devout man. The Scottish Covenanters received their name from signing a Covenant that only Christ could be King, which eliminated the King of England from being God’s representative on earth. The King was not happy.

Reverend Alexander Peden, one of the top leaders of the Covenanter Movement, described Brown as “a clear shining light, the greatest Christian I ever conversed with.” High praise indeed; the type you reserve for a man who is killed for your cause.

They say that Brown would have been a great preacher, except he stuttered. Leading Covenanters visited his home and secret church services were held there. Important meetings took place.

Alexander Peden stayed at his house the night before Brown earned his martyrdom and warned of dark times. Peden was something of a prophet when it came to predicting dire events. This time he was right.

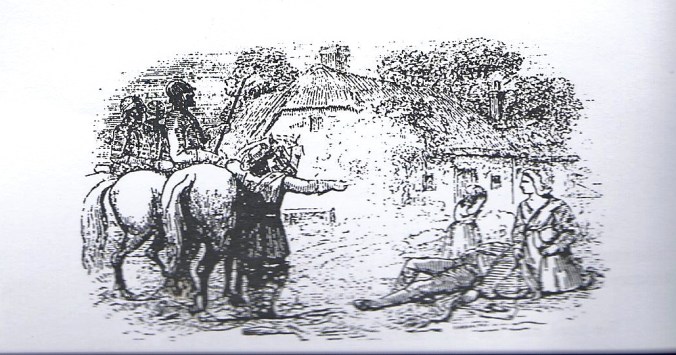

Brown was out gathering peat with his nephew the next morning when soldiers led by John Graham of Claverhouse appeared out of the mist and captured him. The date was May 2, 1685.

Peggy stands near where John Brown was shot on the likely remains of his house. Mist covers the distance as it would have on the day he was captured.

Claverhouse, or Bloody Clavers as the early Presbyterians identified him, was the King’s go-to man when it came to eliminating Covenanters. He was not noted for his compassion.

Covenanter’s martyr graves are found throughout the Scottish Lowlands. This woman was staked out in the ocean to be drowned. If violent deaths create ghosts, the Scottish Lowlands are filled with them.

He took Brown back to his home and demanded that he swear an oath to the King in front of his wife and children. Brown started praying instead. The legend states that Claverhouse ordered his soldiers to kill Brown but they refused. So he took out his own pistol and shot him in the head in front of his family.

The story then goes on to describe how Brown’s wife, Isabel Weir, went about the yard collecting pieces of her husband’s brain. (I don’t mean to treat this lightly, but somehow I can’t help thinking about a TV episode of Bones.)

The family eventually escaped to Ireland and then moved on to North America where it settled in Paxtang, Pennsylvania.

John Brown’s appearance on our family chart in 1969 immediately caught my attention. Not many families can claim a certified martyr. When I became serious about genealogy three years ago, I determined I would go to Scotland and find his grave.

It was listed as being near the small town of Muirkirk on Priesthill farm. Priesthill is an old Scottish sheep ranch, dating back to at least the 1600s. This was the time when Scottish Covenanters had gone ‘off the grid’ with their Presbyterian Church and held services out in the open fields hidden away from the prying eyes of the English King and his henchmen. Armed men were posted around the perimeter in case the soldiers came.

Getting caught wasn’t much fun. You could lose your sheep, your cattle, your land and your life. You might find your body quartered and hung up in various communities to provide an example of why you should be a good Anglican.

The Old Church B&B in Muirkirk Scotland where we stayed when searching for John Brown’s grave.

Priesthill was one of the remote sites where the hidden services were held. To get there we drove north on the road in front of our B&B (the Old Church B&B in Muirkirk… highly recommended) for a couple of miles and picked up a dirt road snaking off to the right through a sheep farm.

The road seemed to go on and on; recent rains had turned it into a muddy mess. Our brand new Mercedes rental car bounced along dodging sheep and accumulating glue-like mud mixed with sheep dung. It was still on the car when we returned it to Edinburgh.

Finally the old farmhouse came into sight. A woman was standing on a porch enclosed by a three-foot high rock wall. She was wearing clothes that my great-grandmother times five might have found fashionable. Since we would be walking through her property in search of John Brown’s grave, I got out to talk with her. (Unfortunately, I left my camera behind.)

But she did something strange. She disappeared. Now this was strange in two ways. Obviously she didn’t want to talk with us. She turned her back and walked rapidly toward the door. OK, I could live with that even though we had found most Scots to be friendly and helpful. Possibly she was shy.

What bothered me more was she sank.

It was like she was traveling down an escalator or open elevator. Her head disappeared beneath the stonewall, before she reached the door. I did not see her go inside.

“Maybe there are steps down to an underground cellar,” I thought. Or maybe she merely bent over to work on a flower garden. Curiosity got the better of me. I walked over. There was no woman; there were no flowers; there were no stairs. As far as I could see the floor of the porch was solid stone.

I asked Peggy, “Did you see that woman disappear?”

“She went inside,” my logical wife explained.

“Ah,” I said and put the matter out of my mind as we wandered out the indistinct trail across the vacant moors to John Brown’s lonely grave. But the thought wouldn’t conveniently disappear like the woman; it kept nibbling away at me. Later I asked Peggy if she had seen the woman sink into the porch.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Did you actually see her go in the house?”

“No.”

So I rest my case for a possible ghost. We did, by the way, find John Brown’s grave. His ghost was said to have appeared gloatingly in Clavers’ tent the night before Clavers was killed in battle.