Next post: It’s on to the Danube River and Vienna!

Next post: It’s on to the Danube River and Vienna!

When I left Alaska in 1986 after three years of working as an executive director of a non-profit focused on health and environmental issues, I took six months off to solo backpack various locations in the West. My first stop was the Grand Canyon, perhaps not the best location to kick off a season of backpacking. Day one was spent hiking down the Tanner Trail from the high peaks on the rim to the scrawny tree on the right. I started with a 70 pound pack, including a generous amount of water. It was a steep, unmaintained, rocky and somewhat dangerous trail of 8-9 miles that dropped 4700 feet with the first source of water being the Colorado River.

Not surprising, I didn’t see another soul along the way and was exhausted when I arrived. I had just enough energy to pump some water, eat a handful of gorp, and throw out my tarp and sleeping bag. I buried my food bag in the sand next to me and crawled into my sleeping bag. That’s when the mouse chose to go dashing across my chest from its home at the base of the tree to my food sack. “Go away Mousey!” I yelled as I dropped into oblivion.

When I woke up in the morning, the first thing I checked was my food bag. Other than helping itself to some peanuts, Mousey hadn’t done much damage. I looked over at the tree to see if I could spot its home. Nope, but I did see something round, grey and skinny on the side of my tarp. “What the” I thought, and then it dawned on me. It was Mousey’s tail! Something had sat on the edge of my tarp and eaten the mouse during the night!

Most of our adventures start with a fair amount of forethought. Our 18-day raft trip through the Grand Canyon was an exception. It started with a phone call from our friend Tom Lovering.

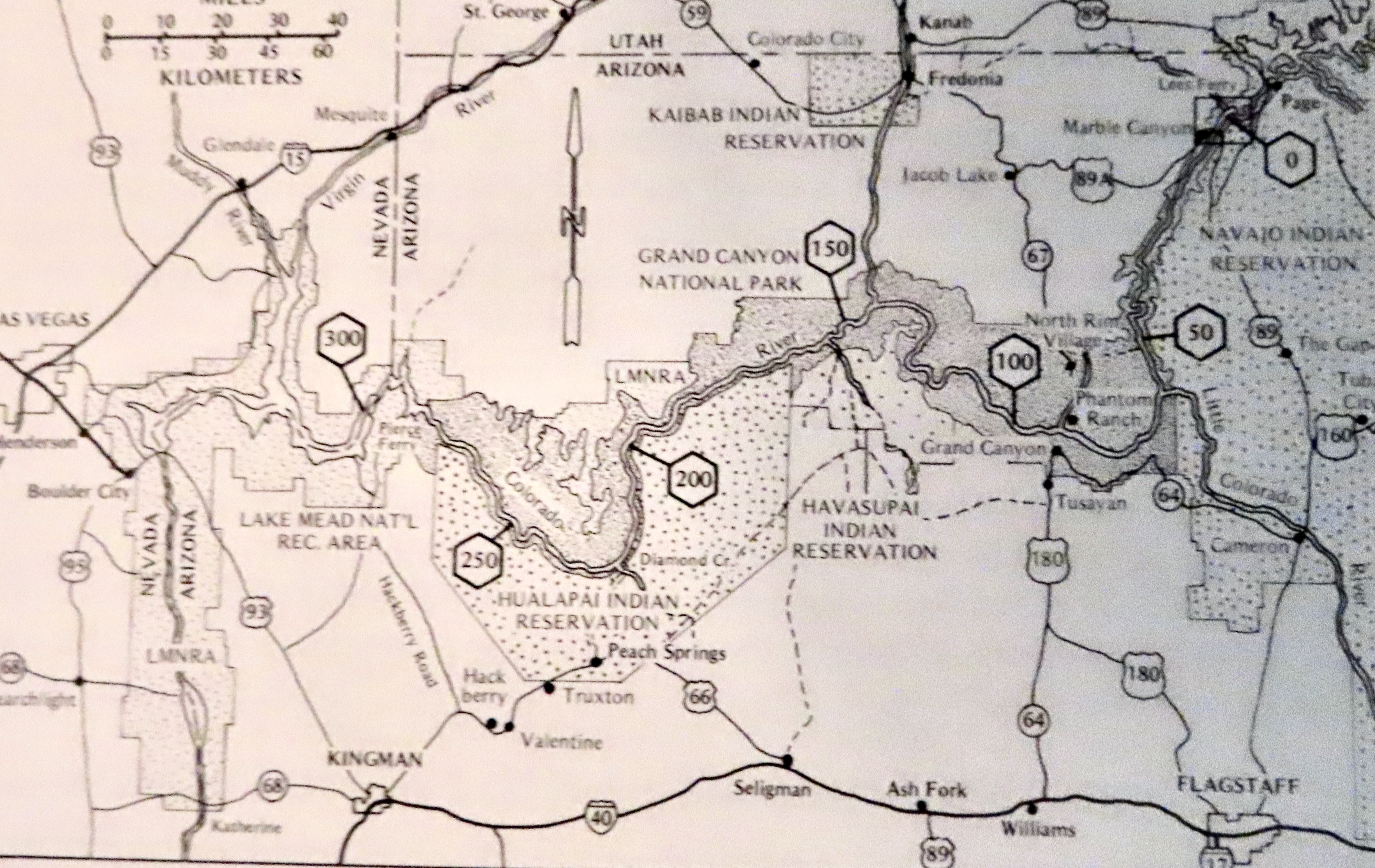

“Curt, you need to jump online right now and sign up for a chance to win a lottery permit to raft the Grand Canyon.” It was more in the nature of a command than a request. Tom was plotting. There are relatively few private permits granted every year in comparison to the ton of rafters who want them. Floating down the Colorado through the Canyon is one of the world’s premier raft trips, providing a combination of beauty and adventure that are rarely matched. Tom figured that the more people he persuaded to sign up for the lottery, the better the chances of getting a permit. He’d made the request to several friends.

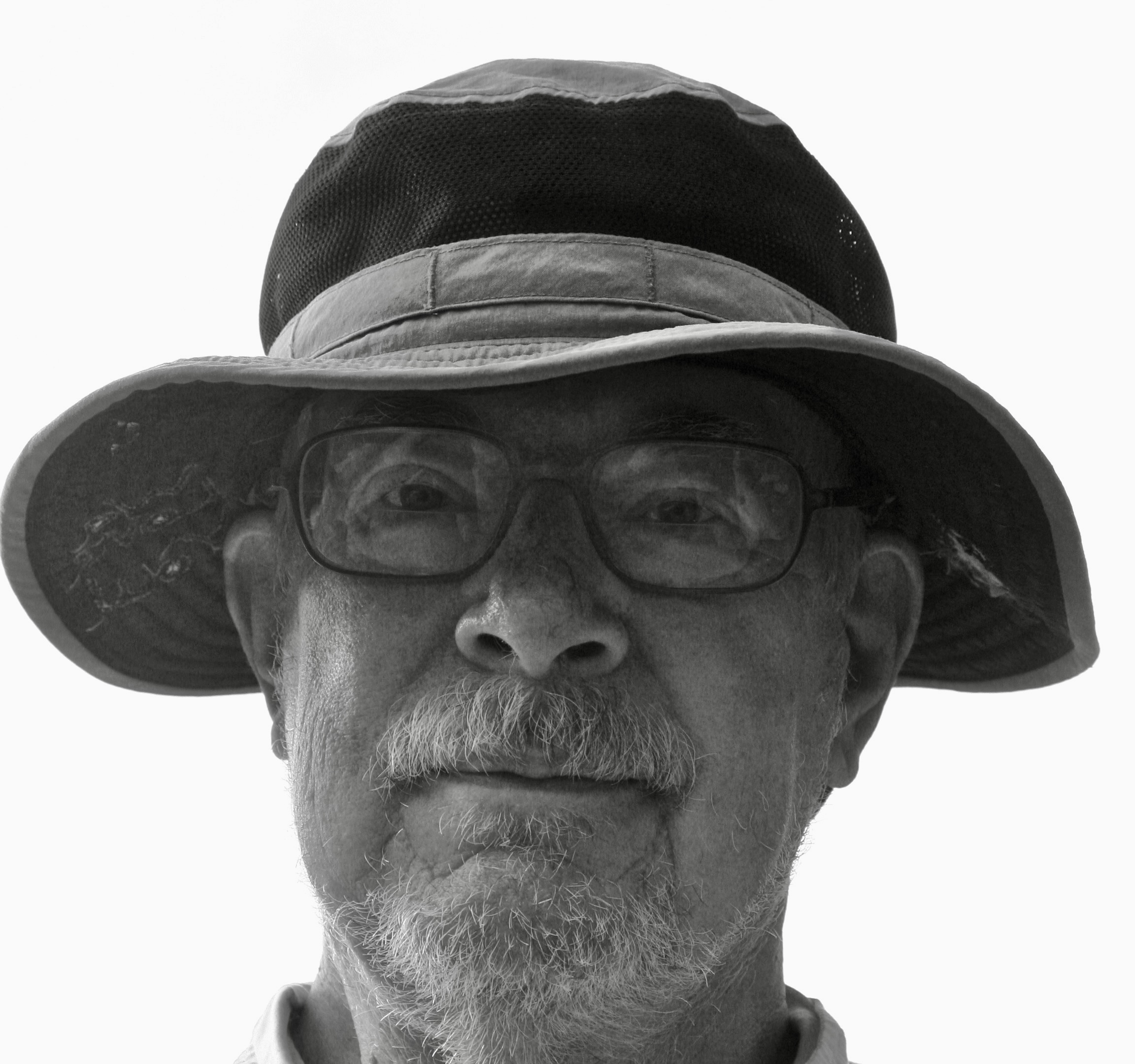

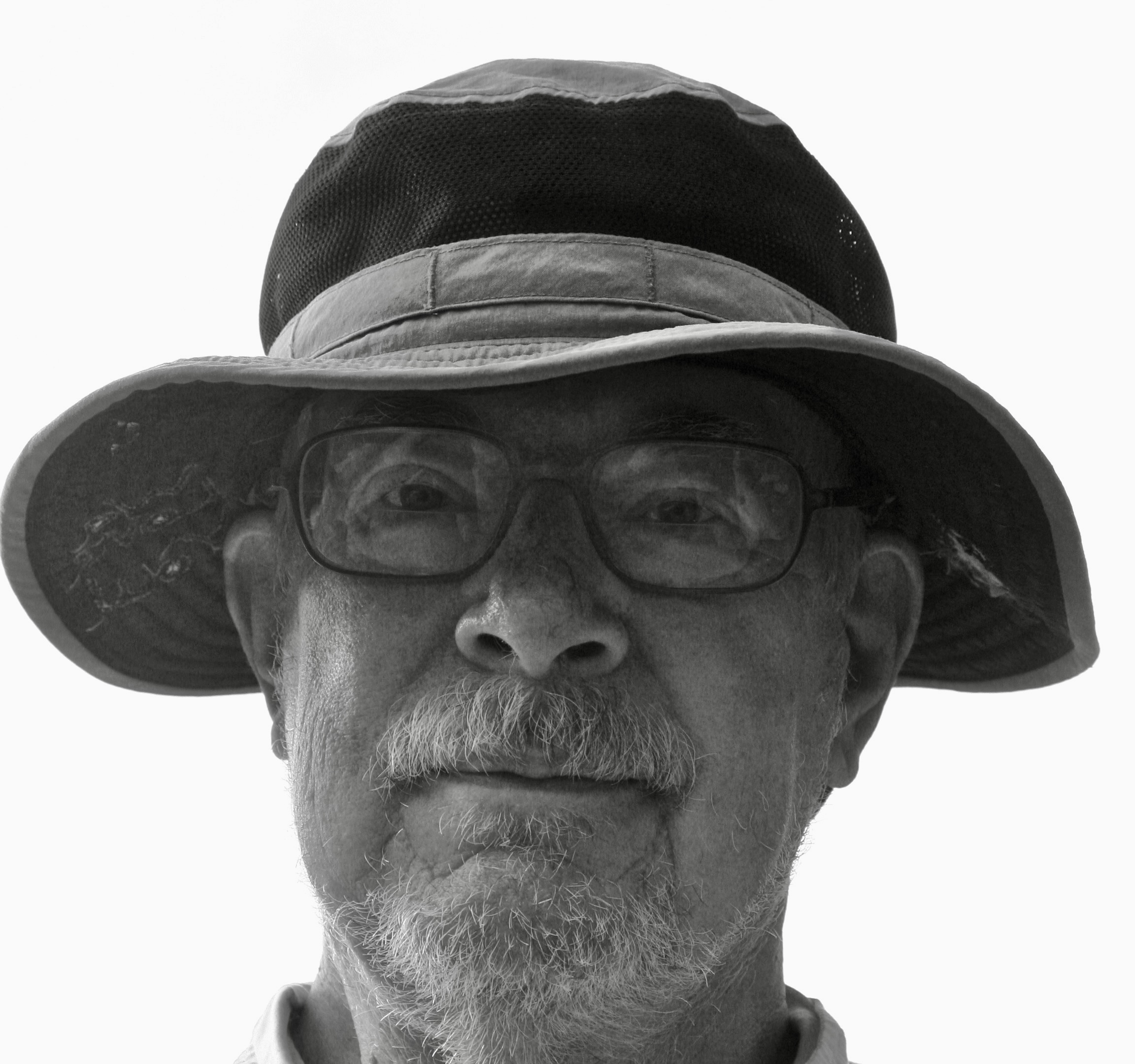

I would have probably skipped the opportunity. We were in the midst of wrapping up a three year exploration of North America and were seriously looking for a place to light— a semi-wilderness home. We were closed to settling on Southern Oregon. We had an hour to meet the filing deadline and the chances of winning, as I mentioned, were close to zilch. Plus I was woefully out of shape and 67 years old. I wasn’t sure that my body would have a sense of humor about the journey. Floating down the river on a private trip actually involves a substantial amount of work and everyone is expected to do their share. Rightfully so.

My child bride Peggy, however, who is seven years younger than I am and loves everything related to water, went straight to the site, filled out the required information in my name, filled out another in hers, and hit send. Fine, I thought to myself. That’s that. We can go merrily on our way and report back to Tom that we tried.

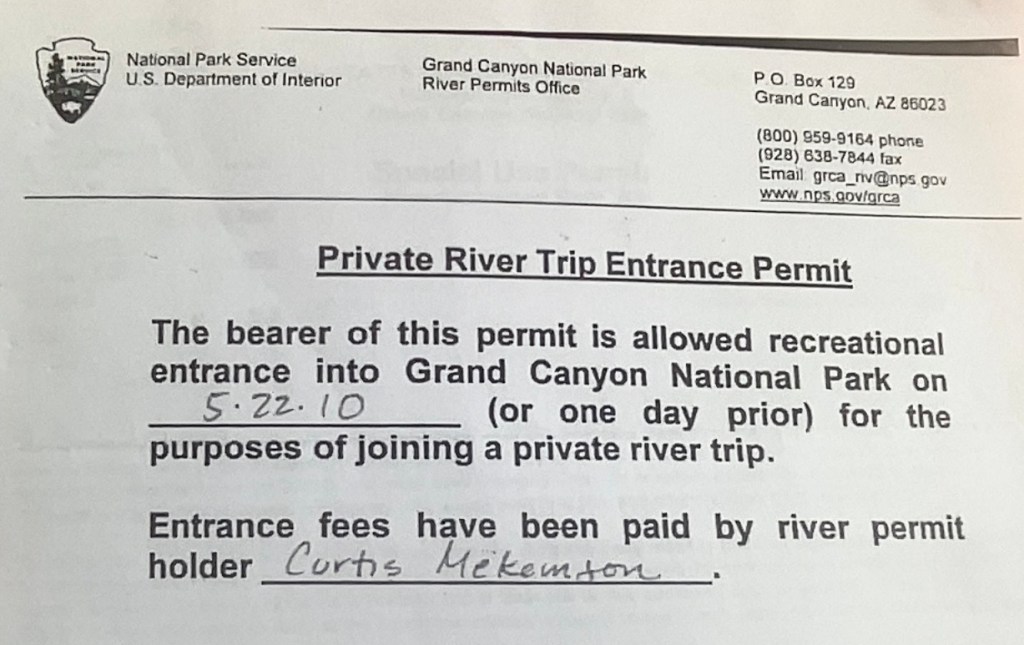

What I wasn’t expecting, as those of you have read my blogs about the trip know, was waking up the next morning and finding an email from the National Park Service announcing that I had won a permit. “Woohoo!” Peggy yelled. “Oh crap,” my fat cells responded. Tom didn’t believe me when I called him from somewhere in Nebraska. It took several minutes to convince him. And then he got excited. Here’s the actual permit:

My first task was to make sure that Tom would do the majority of the work in setting up the adventure. We didn’t have the time and I didn’t have the expertise for a white water raft trip. My experience was in organizing and leading long distance backpack and bicycle adventures. Tom, on the other hand, was an experienced white water enthusiast who had run the river several times and had boundless energy. Plus, he had volunteered. “There is a fair amount of paper work for you and certain responsibilities,” he mentioned in passing. Paper work, as I recall was a 40 page document, maybe it was 400. The responsibility, I learned was daunting. If we screwed up in some way by breaking the Park’s environmental or safety rules, I was accountable and subject to a large fine.

The raft trip in 2010 was the first blog series I ever did. I reposted it in 2018. Since I have already blogged extensively about the journey, I am going to use this and my next two posts as a summary of the trip and include many photos I didn’t use before.

I will note here that while the trip was even more physically challenging than I expected— and there were times I could have strangled Tom (and vice-versa, I’m sure)— I owe him a debt of gratitude for the opportunity. I love the Canyon and have explored it in many ways over the years including five backpacking trips into it. The river trip provided a whole new way to experience the beauty. Traveling with a great group was icing on the cake.

That’s it for the preparations. Now the ‘fun’ begins. The wind was back! We spent our first day fighting headwinds with gusts up to 60 miles per hour. If my dreams of a leisurely float down the river hadn’t already been demolished, they were now. We actually took turns with our boatmen rowing double. All of the photos were taken by either Don, Peggy, or me. I’ll note which ones are Don’s.

My post next Monday will take us from Lees Ferry to just below Phantom Ranch. Thursday is Halloween, however, and Peggy and I have a special treat for you, a tour of Dracula’s castle in Transylvania that we visited 2 1/2 weeks ago on our Danube River trip.

I am sitting on the edge of the Colorado River, red with mud. (Peggy took this photo when I returned with her down the Tanner Trail into the Grand Canyon several years after my first trip. I didn’t have a camera the first time.)

At the end of my last blog on my backpacking trip into the Grand Canyon, I was getting ready to hike up the Canyon to the Little Colorado River. The day before I had made a strenuous descent from the rim to the Colorado River that had left my downhill muscles screaming for mercy.

I hoisted my backpack and mentally prepared for the day’s journey. On the edge of my campsite was a 20-foot section of small boulders I needed to negotiate to rejoin the trail. Normally I would sail through such an obstacle course, stepping on or between rocks as the situation called for. Not this time. I wobbled uncontrollably when I stepped on top of my first rock; I had absolutely zero balance. My muscles were refusing to function. They had gone on strike! While I didn’t reach the insane-cackle level brought on by exhaustion the night before, I did find myself giggling. Dorothy’s Scarecrow was a paragon of grace in comparison to me. I actually made it a whole hundred yards before declaring that my backpacking day was over.

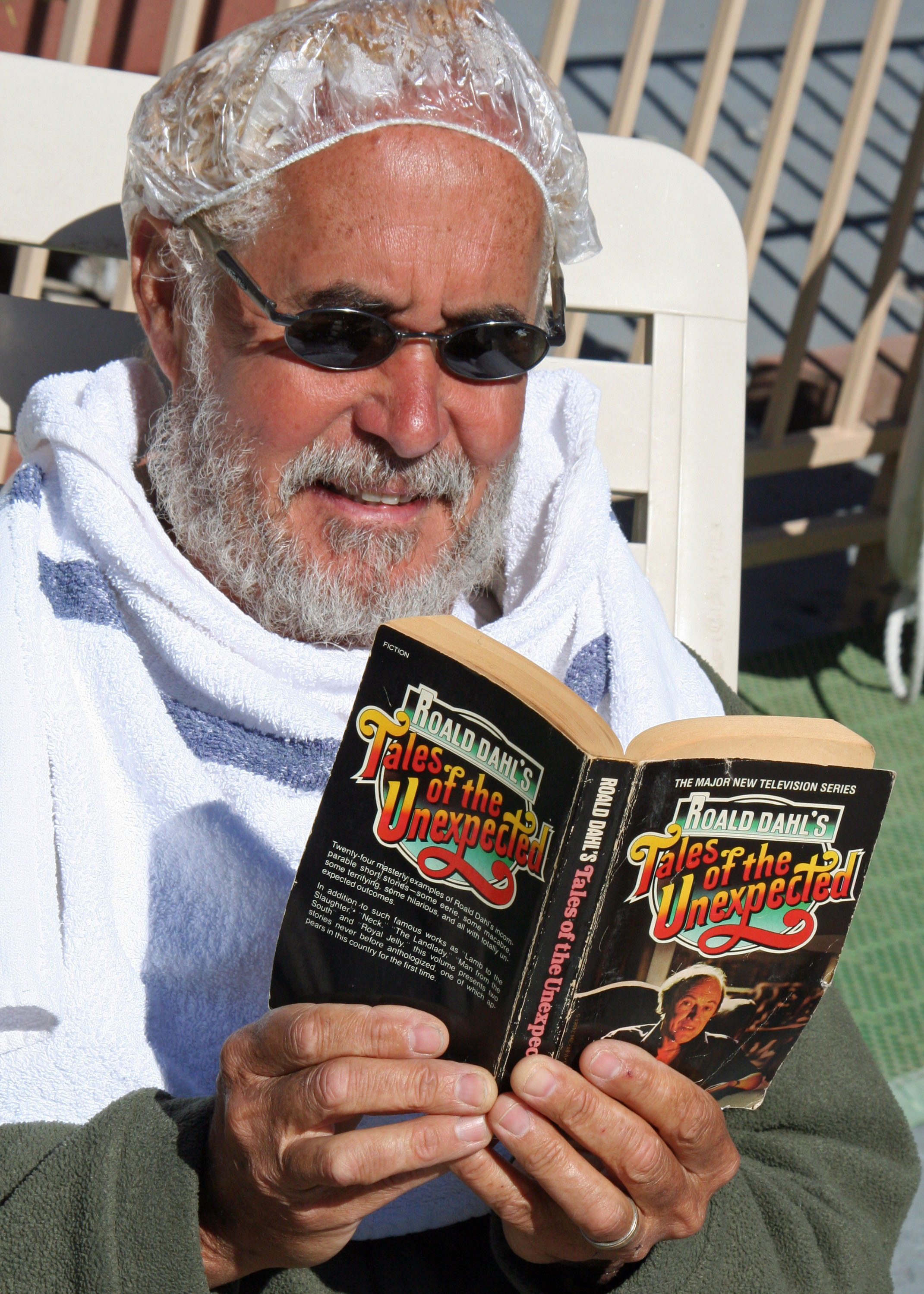

An overhanging rock provided shade and a scenic view of the Tanner Canyon Rapids. I spent the day napping, reading a book on the Grand Canyon by Joseph Wood Krutch, snacking, and watching rafters maneuver through the rapids. The most energy I expended was to go to the river and retrieve a bucket of water. There was plenty of time to let the mud settle.

I made it as far as an overhanging rock a hundred yards from my campsite. Thirteen years later I pointed out my hideaway to Peggy. It may hold the record for the shortest backpacking trip in history. (Photo by Peggy Mekemson.)

The view I had of the Tanner Rapids from my ‘cave.’ Eventually I rafted down the Colorado River and would pass through these rapids.

That evening I sipped a cup of tea laced with 151-proof rum and watched bats flit around my ‘cave’ as they gobbled down mosquitoes. They were close enough I could have touched them. It was like I was invisible, as I had apparently been to the Mousy and his stalker the night before. Strange, unsettling thoughts of nonexistence went zipping through my mind. Being alone in the wilderness is conducive to such thinking. The Canyon adds another layer.

Day three arrived and it was time to explore my surroundings and whip my protesting muscles into shape. I still wasn’t ready for primetime backpacking, so I took a day hike up Tanner Creek Canyon. Whatever creek had existed was waiting for future rain, but the erosive power of water was plainly evident. This was flash flood country where a dry wash can turn into a raging torrent in minutes. Dark clouds demand a hasty retreat to higher ground. I had nothing but blue skies, however, so I hiked up as far as I could go. The canyon narrowed down to a few feet and traveling any further called for rock climbing skills I didn’t possess. I sat for a while enjoying the silence— and the thousands of feet of soaring walls. The isolation seemed so complete it was palpable. I was alone but not lonely. Nature was my companion. Reluctantly, I turned back toward my camp.

I spent the next two days hiking along the River. I backpacked up the Colorado following the Beamer Trail to Lava Canyon Rapids the first day and then worked my way back down past Tanner Creek to Unkar Creek the second. My general rule was that if the trail appeared ready to make a major climb up the canyon, it was going without me.

At one point when Peggy and I were backpacking up the Beamer Trail we came to a fork in the trail and went left. (Yes, we did find the fork that someone had humorously placed in the trail. I was reminded of the Muppet Movie where Kermit came on a similar fork.)

The only real excitement came toward the end of the second day when I discovered my left foot poised a few inches above a pinkish Grand Canyon Rattlesnake that lay stretched across the trail, hidden in the shadows. He was a granddaddy of a fellow, both long and thick. My right leg performed an unbidden, prodigious hop that placed me several feet down the trail. There is a very primitive part of the brain that screams snake. No thinking is required. As soon as I could get my heart under control, I picked up a long stick and gently urged the miscreant reptile to get off the trail. He wasn’t into urging. Instead, he coiled up, rattled his multitude of rattles and stuck out his long, forked tongue at me. He was lucky I didn’t pummel him. I did prod more enthusiastically, however, and he got the point, crawling off the trail rather quickly. I memorized the location so he wouldn’t surprise me on the return journey.

My leg’s miraculous leap suggested that my body was beginning to tune up. There would be no more malingering and feeling sorry for itself. The next day I camped at Tanner Creek again and the following day out I hiked out. The trip up took me three hours less than it had taken to hike in. I was tempted to go find the Sierra Club fellow who had demanded that I use a more civilized trail, but opted out for a well-earned hamburger and cold beer instead. My body was demanding compensation for its forced march.

I’ll return to my Grand Canyon adventure next week when a friend joins me to hike back into the Canyon a few days after I returned to the rim. Hostile spirits from another realm join us. Or at least she believes they do.

NEXT BLOG: I start my series on my recent trip up the North Coast of California. First up— Olompali State Park. Located just north of San Francisco, it has a fascinating history stretching from the Miwok Indians to the Grateful Dead to a hippie commune.

National Parks in the United States and throughout the world protect and preserve many of our most scenic natural areas. This photo is of the Grand Teton Mountains in Wyoming.

Peggy and I decided to take a year off from work in 1999 and travel around North America. I worked as a consultant/citizen advocate on health and environmental issues when I was behaving like a serious adult, and led wilderness treks when I wasn’t. Peggy was fully adult and served as an assistant principal at a middle school.

People were more or less resigned to the fact that I came and went. You might say I was self-employed and self-unemployed. The only person I really had to check with was myself. Peggy’s situation was different, but the school district really wanted to keep her. They offered her an unpaid sabbatical. We bought a travel van and off we went.

We left on July 1. Planning was close to zero. Our only obligations were to meet up with friends for backpacking and kayaking in Alaska and to join Peggy’s parents in Florida for Thanksgiving. Beyond that we could be wherever we wanted to be and do whatever we wanted to do.

Early on, we decided to visit National Parks, Seashores, Monuments and Historical sites whenever we had the opportunity. It was a goal we continued when Peggy retired from being an elementary school principal in 2007 and we wandered in our van for another three years. As a result, we have visited the majority of America’s National Parks as well as many in Canada.

Over the past three weeks I have blogged about a few of the parks we visited. I hope you have enjoyed the journey. Today, I will wrap up this series with photos from several more. I will return to the National Park theme from time to time in the future.

A view of Volcano National Park on the island of Hawaii. The white steam in the background is coming from an active volcano.

A view of the Rio Grande River as it winds through Big Bend National Park in Texas. Peggy and I spent Christmas at the park.

Exit Glacier at Kenai Fjords National Park. I ended backpack treks I led across the Kenai Peninsula near here.

We found this colorful Luna Moth on the Natchez Trace, a National Historic Highway that winds through Mississippi and Tennessee. No commercial traffic is allowed on the road, which makes it great for bicycling. (Photo by Peggy Mekemson.)

This brick outhouse found on the Natchez Trace is included because it is my favorite brick outhouse in the world. I hid out in it with my bicycle as a tornado tore up the countryside nearby.

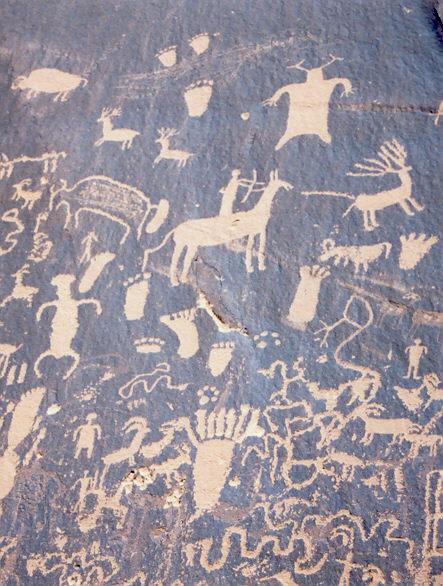

A small section of Newspaper Rock National Historic Site in Utah. Native Americans have been leaving messages on this rock for over a thousand years. Note the guy shooting the elk in the butt with an arrow.

I’ll conclude for today with this photo Peggy took of Capitol Reef National Park in Utah. (Photo by Peggy Mekemson.)

NEXT BLOG: We are off to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico and the beginning of a new series. First up will feature photographs of Pelicans diving for fish in Banderas Bay. We were fortunate to be close to the action and caught some great shots. You won’t want to miss this blog.

Peggy captures Dave Stalheim and me before we hit the river. Note my clean and shaved look. It’s the last time you will see it.

With thoughts of facing wind gusts up to 60 MPH, we begin our journey down the Colorado River through Grand Canyon National Park.

Peggy and I perform the ritual of asking a boatman if we can ride with him. It seems like a strange practice to me, designed to remind us who’s in charge. But we have entered the world where each boatman/woman is the captain of his or her ship, even if the ship is a 16-foot raft with two or three passengers.

“May I have permission to come aboard, sir?” Although it’s more like “Can we ride with you today?” It is courteous but I would prefer to be assigned and have the assignment changed each day.

The tradition is so old that it fades into history. Democracy is not an option on a raging sea or, for that matter, in the middle of a roaring rapid. When the captain yells jump, you jump.

Our boatmen are mellow people, however; good folks. There are no Captain Blighs. If they are slightly more than equal, it goes with the territory. We are committed to riding with each boatman. First up is David Stalheim. He makes his living as a city and county planner in Washington.

“I’ve been applying for a permit to go on the Colorado River for 15 years,” he tells us. Our ten-minute effort of obtaining a permit seems grossly unfair.

We push off from shore, excited and nervous. The wind strikes immediately, like it was waiting in ambush. “Are we moving at all?” Dave asks plaintively.

An old rock road makes its way tortuously down from the canyon rim on river left. (Left and right are determined by direction of travel.) They are important for giving directions as in “There is a raft ripping rock on river right!” Since boatmen often row with their backs facing downriver, they appreciate such information.

The old road is how people once made their way to Lee’s Ferry, which was one of the few ways to cross the Colorado River between 1858 and 1929. The infamous Mormon, John Doyle Lee, established the Ferry. Brigham Young assigned him the job. Later, Lee was executed by firing squad for his role in the Mountain Meadow Massacre where Mormons and Paiute Indians murdered a wagon train of immigrants near St. George, Utah.

After fighting the wind for what seems like hours, we finally come to the Navajo Bridge, which replaced Lee’s Ferry in 1929. It towers some 467 feet above the river and reminds us that we are already miles behind our planned itinerary.

A view of Navajo Bridge and its newer sister looking downstream. The first bridge was built in 1929 and is now used as a walking bridge. The second bridge was built in 1995 to handle modern road traffic.

Just beyond the bridge we catch our first glimpse of Coconino Sandstone. It’s geologic history dates back some 250 million years when a huge desert covered the area and the world’s landmasses were all part of the large continent named Pangaea.

During our journey down the river we will travel through over a billion years of the earth’s history.

The wind continues to beat against us as we make our way down the Colorado River. Only Dave’s strenuous effort at the oars keeps us from being blown up-stream. “Go that way,” I suggest and point down the river.

The group pulls in at a tiny beach in hopes our mini-hurricane will die down. It doesn’t. Dave develops blisters and I develop guilt. A manly man would offer to take over at the oars.

An option floats by. Dave’s niece, Megan Stalheim, is also one of our boatmen. Don Green, a retired Probate Judge out of Martinez, California, is sitting opposite her and pushing on the oars while she pulls. It inspires me. I join the push-pull brigade. Peggy also takes a turn.

The push-pull approach to rowing where Don Green was helping Megan. Peggy and I have been friends with Don for over two decades. He belongs to the same book club we do and joins us on our annual journey to Burning Man (as do Tom and Beth). Don is also quite generous in sharing his excellent photos.

Word passes back to us that Tom wants to scout Badger Rapids. In Boatman terminology this means figuring out the best way to get through without flipping. Badger isn’t a particularly big rapid for the Colorado, but it is our first. We are allowed to be nervous.

There is good news included in the message. We will stop for the night at Jackass Camp just below the rapids on the left. We’ve only gone 8 miles but are eager to escape the wind.

Dave is a cautious boatman. He takes his time to study Badger Rapids from shore and then stands up in his raft for a second opinion as the river sucks us in. Time runs out. Icy waves splash over the boat and soak us. Our hands grasp the safety lines with a death grip as we are tossed about like leaves in the wind. Mere seconds become an eternity. And then it is over.

“Quick, Curt, I need your help,” Dave shouts. We have come out of the rapids on the opposite side of the river from the camp. The powerful current is pushing us down stream. If we don’t get across we will be camping by ourselves. Adrenaline pumping, I jump up and push the oars with all my strength while Dave pulls. Ever so slowly the boat makes its way to camp.

On a private trip down the Colorado through the Grand Canyon National Park, everyone pitches into help. Here we are rigging the rafts. Straps and more straps! (Photo by Don Green)

It is time to make the leap from life on the road to life on the river. Laptops, cell phones, good clothes and the other accoutrements of modern civilization are stuffed into bags and dumped into the van.

Plus I have to paint my toenails. It’s a virgin experience. Grand Canyon boatmen are a superstitious bunch. Many believe their boats will flip if a person is on board with naked toes. And it’s true; boats have flipped under such circumstances. It makes no difference if the opposite is also true.

We were required to paint our toenails so our rafts wouldn’t flip. We didn’t. Maybe it worked. I don’t think, however, that it made our feet prettier.

Tom lectures me. “I will not let you on my boat unless your toenails are painted.” He’s serious. Peggy dutifully applies blue polish on four of my toes. Does this mean we will only half flip?

Two acres of paved boat ramp greet us when we arrive at Lee’s Fairy. The transport van disgorges us as the gear truck makes a quick turn and backs down the ramp. Another private party is busy rigging boats.

From off to the right a longhaired, 50-something man emerges. I think 60’s hippie or possibly the model for a Harlequin Romance cover. The pirate flag on his boat suggests otherwise. A ‘roll your own’ cigarette dangles from his lips. It’s Steve Van Dore, the last member of our group and a boatman out of Colorado. No one in our group has met him but he comes highly recommended.

“Please let this be the truck driver,” Steve later admits is his first thought when he meets our green and purple haired trip leader.

He also confides that Tom hadn’t told him we were a smoke-free group. “On the other hand,” Steve confesses, “I didn’t tell him I am on probation.” Somehow this balances out in Steve’s mind. There is no time to become acquainted; we have work to do.

The dreaded pirate Steve threatens our mascot Bone with a knife and demands to know where he has buried his treasure.

There is an unwritten Commandment on private river trips: Thou Shall Do Your Share. No one is paid to pamper us. Not helping will lead to bad things, like banishment from the tribe.

The truck we loaded in Flagstaff demands unloading. Everybody does everything. There are no assignments. Peggy and I become stevedores. Piles of beer and soda and wine and food and personal gear and ammo cans and hefty ice chests quickly accumulate around the truck.

There is no shade and the desert sun beats down ferociously. It is sucked up by the black asphalt and thrown back at us. We slather on sun block and gulp down water.

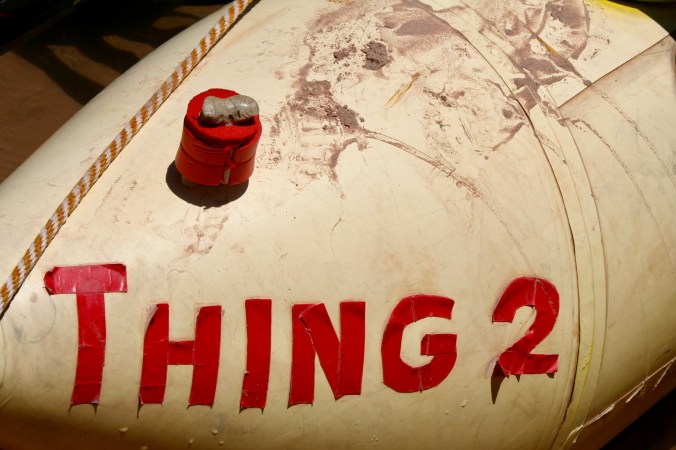

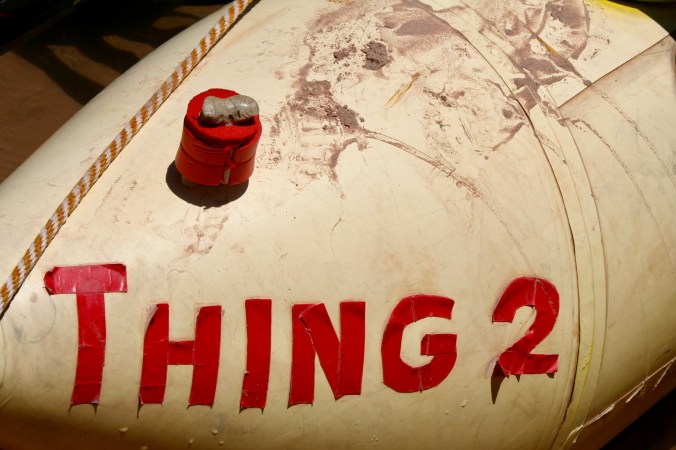

The rafts are unloaded last. Rigging our five rafts is technical but relatively easy, assuming of course one is mechanically oriented. I make no such claims. Steve’s Cat (catamaran) is already set up and in the water, its pirate flag flapping in the breeze. Our other four boats are self-bailing Sotar Rafts with aluminum frames. Tom owns his own, a blue 14 footer named Peanut. The three we have rented are yellow, 16 feet long and nameless.

Tom is the last to rig his boat and it is approaching dusk. I hike down the river to find a campsite for our group while the rest boat down. Peggy and I are totally exhausted. We struggle to set up our new tent in 30 MPH winds. A van is coming to pick us up for dinner and we are late.

The walls of the restaurant are covered with photos of rafts and rafters being trashed by rapids.

The windstorm has changed to a dust storm as we crawl into out tents. It covers everything and gets into my eyes, ears, nose and mouth. I pull out a handkerchief to cover my face. I finally fall asleep with the wind ripping at our tent.

We are awakened at five AM the next morning, as we will be every day of our trip. There is personal gear to pack, breakfast to eat, and boats to load. Any thoughts of a leisurely trip down the river are dashed in the cold reality of the early morning’s light.

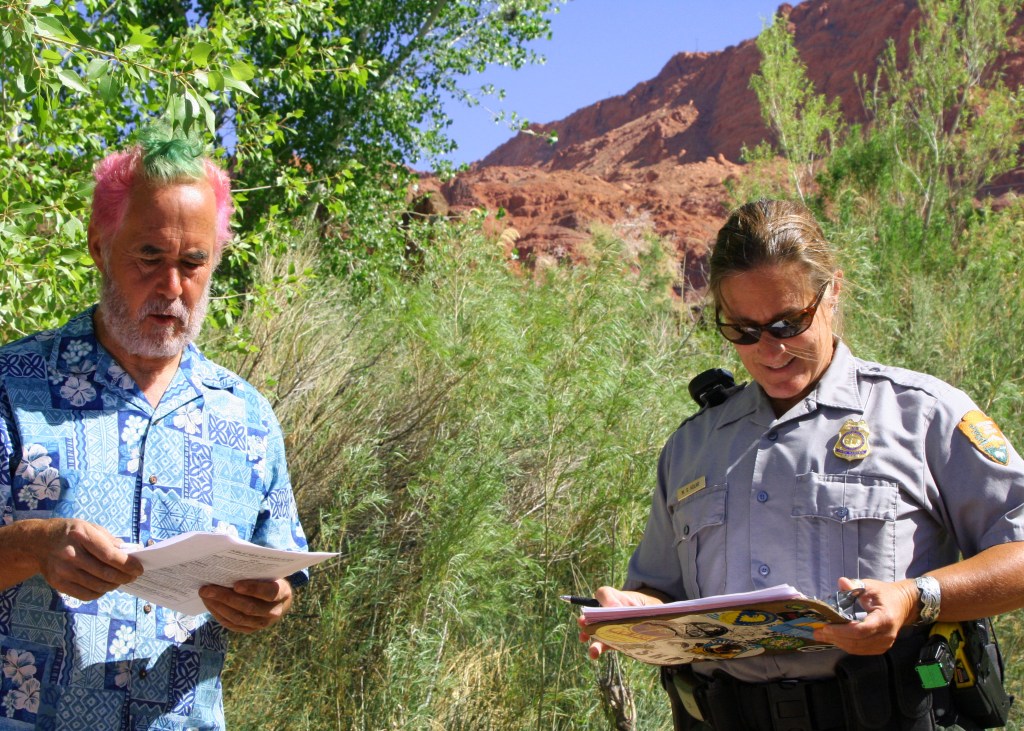

We also have a lecture on the Grand Canyon’s numerous rules by Ranger Peggy. Somewhere in the middle of rigging boats the previous day she had stopped by to check our equipment. Life vests had been dutifully piled up; stoves and bar-b-que were unpacked. Even the groovers, which I will describe later, stood at attention. You don’t mess with Ranger Peggy.

She knew Tom from other river trips and was amused by his hair-do. He introduced me as the permit holder. “Tom’s in charge,” I noted. The smile dropped from her face. “You are responsible,” she said icily. “I’ll try to keep Tom under control,” I replied meekly. Yeah, fat chance that.

Bells, whistles and alarms started going off in my head. I will face heavy fines if any of our party misbehaves. Dang, why hadn’t I read the fine print?

Our second encounter with Ranger Peggy begins after the boats are packed. Tom starts off with a discussion on river safety. Naturally we are required to wear our safety vests any time we are on the boat.

Tom, with his interesting hairdo, and Ranger Peggy check their lists to see which of the many rules they have forgotten to inform us about.

What’s the first rule if we fall overboard: Hang onto the boat. What’s the second rule? “Hang onto the boat,” we chant in unison. And so it goes. Tom saw his wife, Beth, go flying by him last year as he bounced through a rapid. He caught up with her down river.

If the raft flips, what do you do? Hang onto the boat! “Easier said than done,” I think.

“Your head is the best tool you have in an emergency,” Ranger Peggy lectures. Right. When the river grabs you, sucks you under the water, and beats you against a rock, stay cool.

For all of the concern about safety on the river, the Park Service seems more concerned about our behavior on shore.

Over 20,000 people float down the river annually. And 20,000 people can do a lot of damage to the sensitive desert environment. Campsites are few and far between and major ones may have to accommodate several thousand people over the year.

Picture this… 20,000 people pooping and peeing in your back yard without bathroom facilities. It isn’t pretty. So we pack out the poop. And we pee in the river…

Packing out poop makes sense. But peeing in the river, no way! I’ve led wilderness trips for 36 years and for 36 years I’ve preached a thousand times you never, never pee in the water. Bathroom chores are carried out at least 100 yards away from water and preferably farther.

The first time I line up with the guys I can barely dribble out of dismay.

The rules go on and on. Mainly they have to do with leaving a pristine campsite and washing our hands. Normally, I am not a rules type of guy but most of what Ranger Peggy is preaching makes sense. Sixteen people with diarrhea is, um, shitty.

And I enjoy the fact our campsites are surprisingly clean. The least we can do is leave them in the same condition we find them, if not better. The rules work.

Finally… we are ready to launch. Eighteen days and 279 miles of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon lie ahead. Ranger Peggy has checked our IDs and we are who we claim to be. The boatmen have strapped down the gear… and Tom is anxious.

The same up-canyon winds that whipped sand into our tent last night are threatening to create a Herculean task of rowing. Headwinds of up to 60 MPH are predicted.

Next blog: Our first three days on the river.

I have often wondered what part, if any, the strange rock formations in the Grand Canyon played in the development of the Hopi belief about Kachina deities.

Five squirrels with long tufted ears just went charging past our van… in a row. I think it must be love and Peggy agrees. We speculate a female is leading the boys on a glorious romp. “Catch me if you can!” she giggles. The Albert Squirrels are excited to make babies and perpetuate the race, or species, if you want to be biologically correct. Lust is in their hearts. Or maybe it’s just the guys working out territorial differences.

We are located at a KOA in Flagstaff, Arizona as we prepare for our raft trip down the Colorado River. It’s a big campground. Everywhere we look men and women wearing yellow shirts are busily preparing for the onslaught of summer tourists. It feels like a beehive, or squirrel’s nest. The camp cook tells us 28 people work here. Jobs are highly specialized. The man who straightens out misplaced rocks stopped by to chat with us this morning.

Yesterday we watched two employees struggle for an hour on laying out the base of Teepee. It had all the flavor of an old Laurel and Hardy film. They kept measuring and remeasuring the angles, first one way and then the other. I expected one to leap up and start chasing the other around camp with a 2×4.

We wonder what the Kachina deities who live in the San Francisco Mountains overlooking our campground think about the squirrelly activity taking place beneath them. There are bunches of them up there, over 300 according to Hopi lore, and each one has a lesson to teach, wisdom to disperse. They come down from their perch in the winter to share their knowledge. I suspect they would have made quick work of the Teepee project.

Peggy and I hike up the mountain following Fat Man’s trail. Of course there is no irony here as we desperately try to beat our bodies into shape for the Canyon trip. The trail’s name suggests this is a gentle start. Instead it takes us straight up into a snowstorm. The Kachinas are rumored to mislead people under such circumstances.

Once they had the mountain to themselves but now they have competition. Technology has arrived. Tower after tower bristling with arrays of tracking, listening and sending devices look out over the sacred lands of the Hopi, Navaho and other Native Americans.

It’s hard not to think Big Brother is watching. Or not be disturbed by the towers’ visual intrusion. But their presence means we can get cell phone coverage and climb on the Internet. We are addicted to these modern forms of communication so it is hypocritical to whine, at least too much.

But back to the squirrel theme, Peggy and I are a little squirrely ourselves as we go through our gear and get ready for our grand adventure. I am nervous. This is my first multi-day river trip. What have we gotten ourselves into? Do we have the equipment we need? Will we survive the rapids? What will the people who are joining us be like? What challenges will we face that we are ill prepared for? There are many questions and few answers.

I finished my last blog with a picture of this view across the Colorado River from my camp near Tanner Rapids. This and the photo below demonstrate how much color depends on the time of day.

Close to the same shot midday, and the reason why you want to visit the Grand Canyon early in the morning and late in the afternoon.

After my close encounter with the Mouse’s tail, I was ready for breakfast. (See my last post below.)

I visited a bush, fired up my MSR white gas stove and soon had a cup of coffee in my hand and hot morning gruel (oatmeal) in my tummy. I dutifully downed my daily ration of five dried apricots. With breakfast out of the way and a second cup of coffee to enjoy, it was time to get out my topographic map and contemplate the adventure of the day.

My intention was to work my way up the Colorado River following the Beamer Trail to where it was joined by the Little Colorado. It was one of the least traveled trails in the Canyon and chances were I would have it to myself.

The trail was named after a prospector who had searched the area for gold in the 1800s, but it also incorporated ancient sections of trail the Hopi Indians had used to reach their sacred salt mines. Hopi legend claims their ancestors emerged into this world from a cave in the bottom of the Little Colorado River Canyon.

I found the combination of history, mythology, isolation and scenery quite attractive and was eager to get underway. Unfortunately, my body had other plans. It was going on strike.

On the edge of my campsite was a 20-foot section of small boulders I needed to negotiate to rejoin the trail. Normally I would sail through such an obstacle, stepping on and between rocks as the situation called for. My first step on top of a rock sent me crashing down.

I had absolutely zero balance. My muscles were refusing to function. While I didn’t reach the insane cackle level of the day before, I did find myself giggling. Dorothy’s Scarecrow was a paragon of grace in comparison to me. I made it a whole hundred yards before declaring that the day was over.

An overhanging rock provided shade, protection from the elements, and a view of the Tanner Canyon Rapids. I spent the day napping, snacking and watching rafters maneuver through the rapids. I also read a book on the Grand Canyon by Joseph Wood Krutch. The most energy I expended was to go to the river and retrieve a bucket of water. There was plenty of time to let the mud settle.

I made it as far as an overhanging rock a hundred yards from my campsite. Thirteen years later I pointed out my hideaway to Peggy. It may hold the record for the shortest backpacking trip in history.

That evening I sipped a cup tea laced with 151-proof rum and watched bats fly through my ‘cave’ picking off mosquitoes. They were close enough I could have touched them. It was like I was invisible, as I had apparently been to the mouse and the night stalker. Strange, unsettling thoughts of nonexistence went zipping through my mind. Being alone in the wilderness is conducive to such thinking. The Canyon adds another layer.

Day three arrived and it was time to explore my surroundings and whip my protesting muscles into shape. I still wasn’t ready for backpacking so I took a day hike back up Tanner Creek Canyon. Whatever creek had existed was waiting for future rain but the erosive power of water was plainly evident. This was flash flood country where a dry wash can turn into a raging torrent in minutes. Dark clouds demand a hasty retreat to higher ground.

I had nothing but blue skies, however, so I hiked up as far as I could go. The canyon narrowed down to a few feet and traveling any further called for rock climbing skills I didn’t possess. I sat for a while enjoying the silence and soaring walls. The isolation seemed so complete it was palpable. I was alone but not lonely. Nature was my companion. Reluctantly, I turned back toward my camp.

I spent the next two days hiking along the River. I backpacked up toward Lava Canyon the first day and then worked my way back down past Tanner Creek to Unkar Creek the second. My general rule was that if the trail appeared ready to make a major climb up the canyon walls, it was going without me.

Here I am hiking up river toward the Little Colorado following a route that ancient Hopi Indians may have used.

At one point when Peggy and I were backpacking up the Beamer Trail, we came to a fork in the trail and went left. (Yes, we did find the fork.)

The only real excitement came toward the end of the second day when I discovered my left foot poised five inches above a Grand Canyon Rattle Snake that lay stretched across the trail, hidden in the shadows. He was a granddaddy of a fellow, both long and thick. And pink. My right leg performed an unbidden hop that placed me several feet down the trail. There is a part of the brain that screams snake. No thinking is required.

As soon as I could get my heart under control, I picked up a long stick and gently urged Mr. Pink off the trail. He wasn’t into urging. Instead, he coiled up, rattled his multitude of rattles and stuck out his long, forked tongue at me. He really did want to sink his fangs into my leg. I prodded more enthusiastically and he crawled off, albeit reluctantly. I memorized the location so he wouldn’t surprise me on the return journey.

My leg’s miraculous leap did suggest that my body was beginning to tune up. There would be no more malingering and feeling sorry for itself. The next day I camped at Tanner Creek again and the following day out I hiked out. The trip took me three hours less than it had taken to hike in. I was tempted to go find the Sierra Club fellow but opted out for a well-earned hamburger and cold beer instead. My post-pudgy body demanded compensation.

A final view of where I had backpacked. You can see the Tanner Trail winds down the ridge on the left.

Looking down from Lipan Point at the start of the Tanner Trail. The sharp bend in the Colorado River… far away, is where I am heading. (The photos of the trail down I actually took several years later when I backpacked in with Peggy.)

The steep trail seemed to disappear under my feet as I began my journey and descended through millions of years of earth history. About a half of mile down it disappeared for real, having been washed away by winter rains. “I told you so,” my body whispered loudly as I mentally hugged the side of the canyon and tentatively made my way around the washout.

Steep drop offs are a common factor in all trails leading into the Grand Canyon. The first trails were created by Native Americans. Later miners, rustlers, and entrepreneurs interested in promoting tourism would enhance the original trails and create new ones.

I am not sure when my legs started shaking. Given the stair-step nature of the trail and the extra weight of the pack, my downhill muscles weren’t having a lot of fun. Fortunately, Mother Nature provided a reprieve.

The erosive forces of wind and water that have sculpted the mesas and canyon lands of the Southwest are more challenged by some types of rocks than others. Somewhere between two and three miles down I came upon the gentle lower slopes of the Escalante and Cardenas Buttes, which allowed me to lollygag along and enjoy the scenery.

I escaped from the sun beneath the shadow of a large rock to drink some of my precious water, nibble on trail food and take a brief nap. It would have made a good place to camp, others had obviously taken advantage of shade and flat surface, but the Colorado River was calling.

Ignoring the ever-increasing screams of my disgruntled body parts, I headed on. At mile five or so my idyllic stroll came to a dramatic halt as the trail dropped out of sight down what is known as the Red Wall. (It received this imaginative name because it is red and looks like a wall. The red comes from iron dissolved in water that runs down from the rocks above. Think rust.) Some fifty million years, or 625,000 Curtis life spans, of shallow seas had patiently worked to deposit the lime that makes up its 500-foot sheer cliff. It is one of the most distinctive features of the Grand Canyon.

The Red Wall, seen here snaking off to the right, is one of the most distinctive features of Grand Canyon National Park.

My trail guide recommended I store water before heading down so I could retrieve it when I was dying of thirst on the way out. I could see where people had scratched out exposed campsites as a place to stop for the night. The accommodations weren’t much but the view was spectacular.

The rest of the five-mile/five month journey was something of a blur. (It was closer to five hours but time was moving very slowly.) I do remember a blooming prickly pear cactus. I grumbled at it for looking so cheerful.

Looking back up the trail provided a perspective on how far I had come. The small, needle-like structure on the rim is Desert View Tower.

I also remember a long, gravelly slope toward the bottom. My downhill muscles had totally given out and the only way I could get down was to sidestep. I cackled insanely when I finally reached the bottom. I was ever so glad the Sierra Club guy wasn’t around to see me.

Setting up camp that night was simple. I threw out my ground cloth, Thermarest mattress, and sleeping bag on a sandy beach. Then I stumbled down to the river’s edge and retrieved a bucket of reddish-brown Colorado River water, which appeared to be two parts liquid and one part mud. I should have waited for the mud to settle. Instead I used up a year of my water filter’s life to provide a quart of potable water.

All I had left to do was take care of my food. Since people camped here frequently, the local critters would see me as a huge neon billboard that blinked ‘Eat at Curt’s.’ Not seeing a convenient limb within three feet, I buried my food bag in the sand next to me. Theoretically, anything digging it up would wake me. Just the top was peeking out so I could find it in the morning.

As the sun went down, so did I. Faster than I could fall asleep, I heard myself snoring. I was brought back to full consciousness by the pitter-patter of tiny feet crossing over the top of me. A mouse was worrying the top of my food bag and going for the peanuts I had placed there to cover my more serious food.

“Hey Mousy,” I yelled, “Get away from my food!” My small companion of the night dashed back over me as if I were no more than a noisy obstacle between dinner and home. I was drifting off again when I once more felt the little feet. “The heck with it,” I thought in my semi-comatose state. How many peanuts could the mouse eat anyway?

The river water I had consumed the night before pulled me from my sleep. Predawn light bathed the Canyon in a gentle glow. I lay in my sleeping bag for several minutes and admired the vastness and beauty of my temporary home. The Canyon rim, my truck and the hordes of tourists were far away, existing in another world.

My thoughts turned to my visitor of the previous evening. Out of curiosity, I reached over for my food and extracted the bag of peanuts. A neat little hole had been chewed through the plastic but it appeared that most of my peanuts were present and accounted for. The small contribution had been well worth my solid sleep.

I then looked over to the right to see if I could spot where the mouse had carried its treasure. Something on the edge of my ground cloth caught my eye. It was three inches long, grey, round and fuzzy.

It was Mousy’s tail!

Something had sat on the edge of my sleeping bag during the night and dined on peanut stuffed mouse. Thoughts of a coyote, or worse, using my ground cloth as a dinner table jolted the primitive parts of my brain. Had I had hackles, they would have been standing at attention ready for action.

I ate a peanut in honor of Mousy’s memory and tossed a few over near his house in case he had left behind a family to feed. I also figured that the peanuts would serve as an offering to whatever Canyon spirits had sent the night predator on its way.

Next blog: I recover and then explore the Canyon. A large, pink rattlesnake and I tangle.