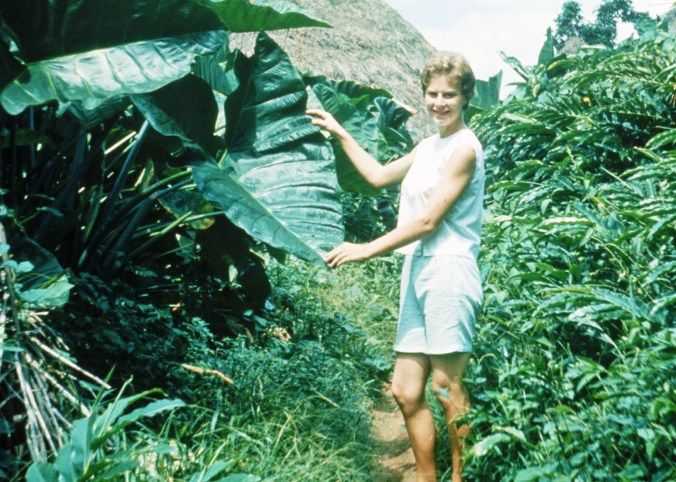

Good teaching involves capturing the imagination of students and encouraging them to become active participants in the classroom. Often it also involves participating in extracurricular activities. In this 1966 photo I am coaching Gboveh’s High School volleyball team in Gbarnga, Liberia.

I am not sure I earned the title of teacher at the elementary school, even though I put in the time and occupied the chair. I did learn that teaching was hard work and developed a life-long respect for elementary school teachers. I like to believe, had to believe, that I had some impact on the life of my students.

High school was different. From the beginning I was teaching subjects I truly enjoyed: World History, World Geography, African History and African Geography. I had never understood how history and geography could be boring. The best of my teachers had brought the subjects to life and made them exciting and relevant. I was determined to do the same for my students. We debated, did projects and made maps.

As strange as it may seem, my high school African History course was a first for Liberia. We travelled back in time starting with the exciting discoveries being made at Olduvai Gorge in East Africa about the early beginnings of humanity. We looked at the major West African kingdoms such as the Songhai and Mali. We explored the impacts of slavery, Colonialism, Islam and Christianity on Africa.

In geography we started locally and moved outward, from Gbarnga to Liberia to Africa and the world. Like their elementary school counterparts, the high school students found it almost impossible to accept that Liberia occupied such a small part of the African Continent. They became incensed, like it was my fault.

I wisely opted out of teaching Liberian History. It’s likely that I would have deviated from the Americo-Liberian version and been run out of the country. How could I teach the kids that Matilda Newport was someone they should idolize when her claim to fame was blasting their great-great-grandfathers with a cannon? I even had to be careful what I taught my World and African History classes. The students were bright and would draw their own conclusions.

“Gee Mr. Mekemson, the way the white minority in South Africa controls things is a lot like Americo Liberians control things here.”

“Oh really?’’ was about as far as I dared go in response. Things had a way of getting back to the authorities. Favors could be earned by reporting supposedly seditious comments to paranoid government officials and I had already earned enough black marks from the second grade reader and Boy’s appetite for Guinea Fowl.

But I didn’t stay out of trouble. During our second semester at Gboveh, I decided that creating a student government would help our students prepare for the future. I argued that the best way to prepare for democracy was to practice it. Everyone, including students, teachers and Mr. Bonal, agreed. We pulled together interested students, worked through developing by-laws, and set up elections. The students even decided they would organize and run for office on party tickets. Why not? It sounded like fun.

It never entered my mind that this relatively innocent gesture would strike terror in the hearts of Americo-Liberians. Once again, I had failed to comprehend just how paranoid the Liberian government was. Within 24 hours we had been accused by the Superintendent of Bong County of setting up competing political parties to the Government’s True Whig Party.

Student leaders were told to cease and desist or they would be arrested and thrown in jail. Mr. Bonal called me in and suggested I should start packing my bags. There was no way that he was prepared to take responsibility. I didn’t blame him. At a minimum he could lose his job… and that would be a stroll through the rainforest in comparison to rotting in a Liberian jail.

On one level, the government’s paranoid behavior made sense. The True Whig Party was how the Americo Liberians maintained control of the government and, more importantly, their privileged positions. The Kpelle Tribe was the largest tribe in Liberia and my students were becoming the elite of the tribe through education. A political party set up at high school might indeed morph into a political party of the Kpelle, given time.

So we eliminated the tickets and names. We were then allowed to proceed but I have no doubt we were closely monitored. I couldn’t help but wonder which of my students or fellow faculty members reported regularly to the Superintendent on my treasonable behavior.

Somewhat on the lighter side was the business of keeping the names of my students straight. It wasn’t that I had a lot to remember; there were five students in the 12th grade, ten in the 11th and sixteen in the 10th. Most teachers would kill for that student-teacher ratio. The problem was that the students changed their names frequently.

John Kennedy was big in Liberia at the time so there were several John Kennedys. Moses was also popular. Five trillion missionaries made sure of it. Kids would also take the name of whomever they were living with. Most of them had left villages and were trying to survive life in the big town. By adopting the name of the family taking care of them, they encouraged better care. Sam even told me he considered becoming Sam Mekemson, our African son. Finally, as students became more aware of their heritage, some switched back to their tribal names. What a unique thought that was.

Roll call was often a challenge. Students wouldn’t answer if I didn’t use their name of the moment. I finally adopted a rule that students could change their names but only at the beginning of a semester. It worked, sort of.

My school activities increased as time went on. I chaired the social studies department from the beginning. This wasn’t too significant since I was the social studies department and my primary responsibility involved keeping me in line. (Some misguided people claim that is not an easy task.) I also took on more work for Mr. Bonal and eventually came close to functioning in the role of vice principal. Daniel Goe had returned to the U.S. for further education.

Jo created a high school chorus that became so good the County Superintendent wanted her to create a Bong County Chorus. She gracefully declined. This was, after all, the same man who wanted to throw us in jail when Boy ate his Guinea Fowl and was ready to kick us out of the country because we dared to develop a student government.

Jo Ann directing her Gboveh High School chorus. At Berkeley, she had belonged to the University’s elite Glee Club.

There were a multitude of other activities. I developed a library for the school by raiding departing PCVs book collections. For some reason I was roped into coaching the school’s football/soccer team, a task I quickly traded for volleyball. (There were four-year olds in town who knew more about soccer than I did.)

I also created a local Boy Scout troop. I taught them how to tie knots and they took me for great jungle walks. Jo Ann contributed by sewing Patrol flags. All in all, we kept busy carrying out the same type of work being done by thousands of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world.