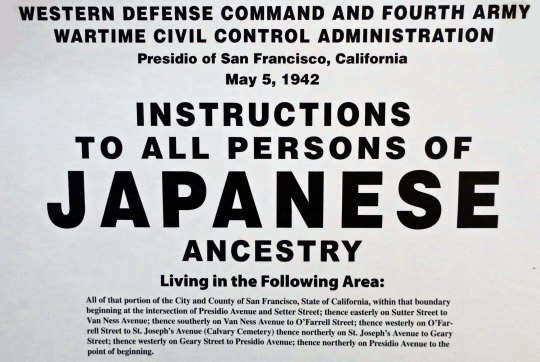

The World War II Japanese ‘relocation center’ of Manzanar is located a short ten miles north of Lone Pine and the Alabama Hills just off of Highway 395. I went there directly from the Lone Pine Museum of Film History. It would be hard to find two more different reminders of our past. As far as I can remember, I didn’t know about the site until I was in college. It wasn’t something that was discussed at my home. Had I been an American citizen with Japanese ancestry as opposed to British ancestry, it’s likely that I would have been born at one of the West Coast “relocation centers,” i.e. concentration camps, behind barbed wire fences overlooked by guard towers bristling with guns.

I may have learned about the camps in high school during American History but it was made real for me at the community college I attended just east of Sacramento in 1961-63. I was student body president in 1962 and a member of my council was a young Japanese American woman who had experienced the relocation effort directly. Her family, along with several other Japanese American farmers in the Loomis/Lincoln area, were rounded up, forced to abandon their farms, and shipped out to Tule Lake where the relocation center for most of Northern California was located.

Ten years later in the early 70s, I would come to know another Japanese American who had been shipped along with his family to Tule Lake as a six-month old child, Bob Matsui. In 1971, working together with other environmentalists, I had created a political organization in Sacramento to elect environmentally concerned candidates to the Sacramento City Council and Board of Supervisors. Bob, who was making his first run for city council, had scored high on a questionnaire that we had put together. I had enthusiastically supported him in his run for election and he had won. Not only did he support environmental issues on the City Council for seven years, he continued to in 1978 when he became the fifth Japanese American to be elected to Congress. He would serve with distinction for a quarter of a century and be known for his bipartisan approach in creating substantive legislation.

More to the point of this post, Bob also became a strong advocate for recognizing the wrongs that had been done to Japanese Americans during World War II. For one, he was instrumental in having Manzanar set aside as a National Historic Landmark. In 1980 he joined Senator Daniel Inouye, and Congressmen Spark Matsunaga and Noman Mineta, in an effort to establish a committee to study the effects of the incarceration and the potential for redress.The end result of this effort was the creation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. After an extensive set of hearings throughout the West, the bipartisan Commission concluded that the decision to incarcerate the Japanese Americans was not based on military necessity and instead was based upon “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Not one Japanese American was found guilty of aiding Japan during World War II.

The findings of the Commission led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which granted wartime survivors an apology and individual reparations of $20,000. While President Reagan initially opposed the implementation legislation, H.R. 422, because of cost, he readily signed the bill when it reached his desk. I found his comments at the signing ceremony to be quite relevant, not only to the legislation, but for today.

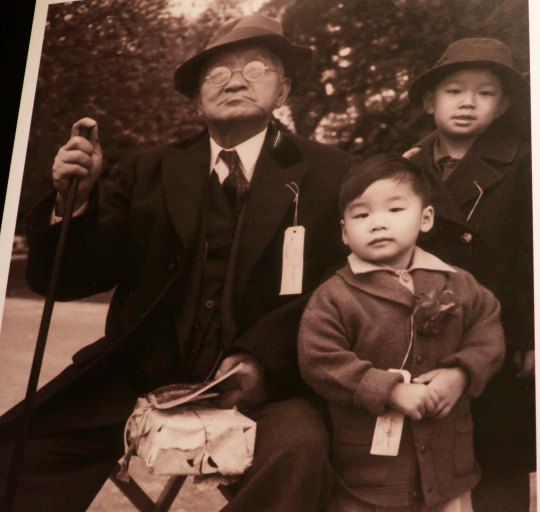

He had started the ceremony by noting “… we gather here today to right a grave wrong. More than 40 years ago, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in makeshift internment camps. This action was taken without trial, without jury. It was based solely on race, for these 120,000 were Americans of Japanese descent.”

Reagan went on to describe H.R. 442: “The legislation that I am about to sign provides for a restitution payment to each of the 60,000 surviving Japanese-Americans of the 120,000 who were relocated or detained. Yet no payment can make up for those lost years. So, what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor. For here we admit a wrong; here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.”

The President concluded his statements by reading a newspaper article from 1945 that had been included in the Pacific Citizen:

“Arriving by plane from Washington, General Joseph W. Stilwell pinned the Distinguished Service Cross on Mary Masuda in a simple ceremony on the porch of her small frame shack near Talbert, Orange County. She was one of the first Americans of Japanese ancestry to return from relocation centers to California’s farmlands. “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell was there that day to honor Kazuo Masuda, Mary’s brother. You see, while Mary and her parents were in an internment camp, Kazuo served as staff sergeant to the 442d Regimental Combat Team (an all Japanese-American regiment). In one action, Kazuo ordered his men back and advanced through heavy fire, hauling a mortar. For 12 hours, he engaged in a singlehanded barrage of Nazi positions. Several weeks later at Cassino, Kazuo staged another lone advance. This time it cost him his life.”

The newspaper clipping noted that her two surviving brothers were with Mary and her parents on the little porch that morning. These two brothers, like the heroic Kazuo, had served in the United States Army.

After General Stilwell made the award, the motion picture actress Louise Allbritton, a Texas girl, told how a Texas battalion had been saved by the 442d. Other show business personalities paid tribute — Robert Young, Will Rogers, Jr. And one young actor said: “Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world: the only country not founded on race but on a way, an ideal. Not in spite of but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way.” (Italics mine)

Reagan then went on to note with his usual sense of humor: “The name of that young actor — I hope I pronounce this right — was Ronald Reagan. And, yes, the ideal of liberty and justice for all — that is still the American way.”

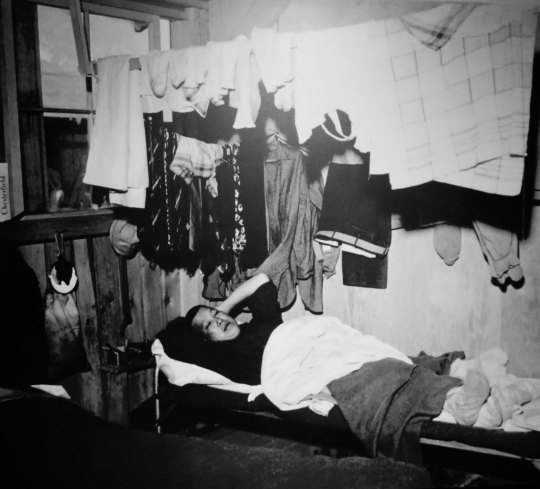

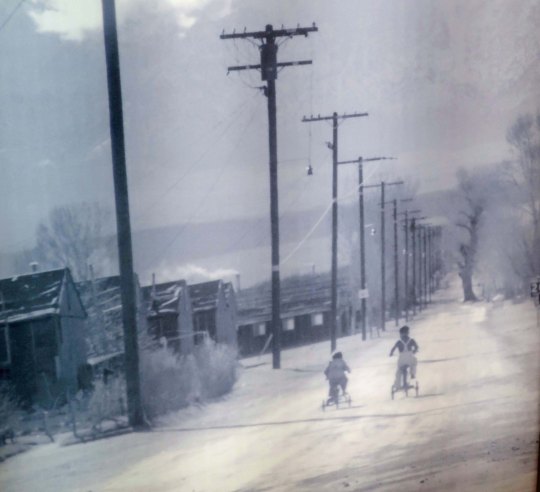

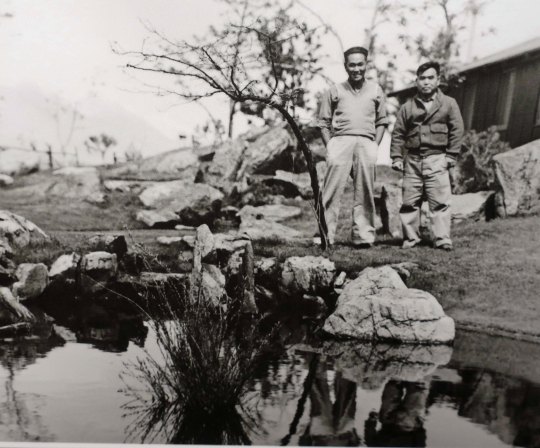

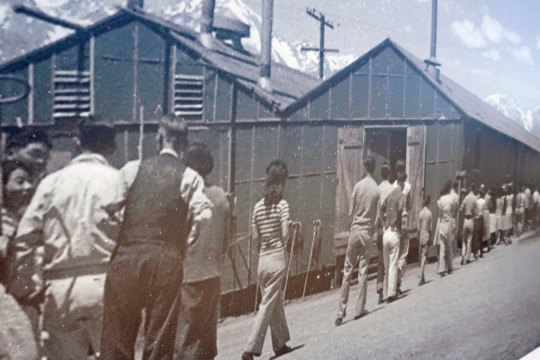

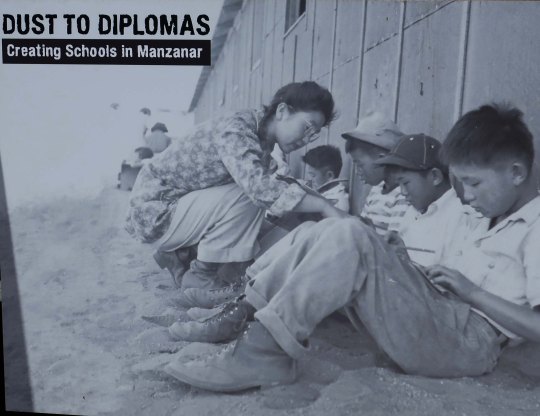

Now that’s what being Presidential, the President of all Americans, is about. Following are several photos I took at Manzanar.

Privacy was extremely limited. Both inside and out.

“Oh, give me land, lots of land under starry skies above. Don’t fence me in. Let me ride through the wide open country that I love. Don’t fence me in. Let me be by myself in the evenin’ breeze, And listen to the murmur of the cottonwood trees. Send me off forever but I ask you please, don’t fence me in”

NEXT POST: The number one reason for driving down Highway 395: Its dramatic mountain scenery.