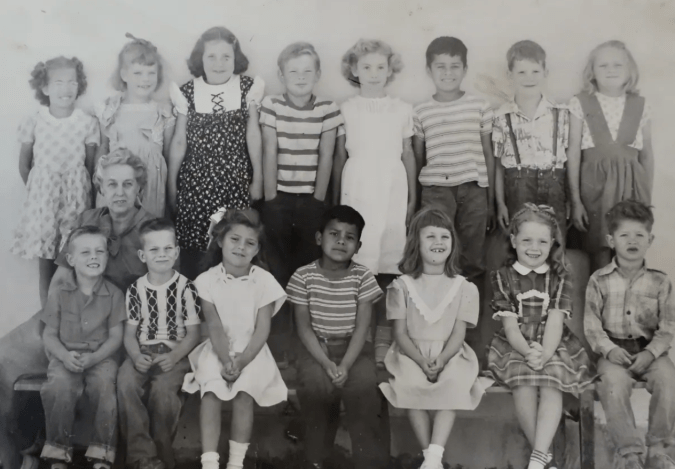

Two of these large incense cedar trees dominated the Graveyard. From an under five-foot perspective, they were gigantic, stretching some 75-80 feet skyward. The limbs of the largest started 20 feet up, providing scant hope for climbing. As usual, Marshall found a risky way around the problem.

Several of the huge limbs came tantalizingly close to the ground at their tips, and one could be reached by standing on the tombstone I used to spy on Demon the Cat when she hid her kittens. But only Marshall could reach it; I was frustratingly short by several inches. Marsh would make a leap, grab the limb, and shimmy up it hanging butt down until the limb became large enough for him to work his way around to the top. Then he would crawl up to the tree trunk, five Curt-lengths off the ground. After that, he would climb to wonderfully mysterious heights I could only dream about.

Eventually I grew tall enough to make my first triumphant journey up the limb. Then, very carefully, I climbed to the heart-stopping top, limb by limb. All of Diamond spread out before me. I could see our school, the mill where my father worked, the woods, and the hill with a Cross where I had shivered my way through at a cold Easter Sunrise Service. I could see the whole world. Except for a slight wind that made the tree top sway and stirred my imagination about the far away ground, I figured I was as close to Heaven as I would ever get.

By the time I finally made it to the top, Marshall had more grandiose plans for the tree. We would build a tree house on the upper branches. Off we went to Caldor, the lumber mill where Pop worked, to liberate some two by fours. Then we raided Pop’s tool shed for a hammer, nails, and rope. My job was to be the ground man while Marshall climbed up close to the top. He would then lower the rope and I would tie on a board that he would hoist up and nail in. It was a good plan, or so we thought.

Along about the third board, Pop showed up. It wasn’t so much that we wanted to build a tree fort in the Graveyard that bothered him, or even that we had borrowed his tools and nails without asking. He even ignored the liberated lumber. His concern was that we were building our fort 60-feet up in the air on thin limbs that would easily break with nails that barely reached through the boards. After he graphically described the potential results, even Marshall had second thoughts.

Pop had a solution though. He would build us a proper tree house on the massive limbs that were only 20 feet off the ground. He would also add a ladder so we could avoid our tombstone-shimmy-up-the-limb route. And he did. It was a magnificent open tree house of Swiss Family Robinson proportions that easily accommodated our buddies and us with room to spare.

It was more like a pirate hideout than a Robinson family home, however. Hidden in the tree and hidden in the middle of the Graveyard, it became our special retreat where we could escape everything except the call to dinner. It also became my center for daydreaming and Marshall’s center for planning mischief. He, along with our friends Allen and Lee, would scope out our forays into Diamond and the surrounding countryside.

And finally, the treehouse became the starting point for the Great Tree Race. We would scramble to the top and back down in one-on-one competition as quickly as we could. Death-defying is an appropriate description. Or maybe, suicidal. Slips were a common hazard. Unfortunately, the other boys always beat me; they were one to three years older, and I was the one most susceptible to losing my grip. My steady diet of Tarzan comic books sustained me, though, and I refused to give up. Eventually, several years later, I would triumph.

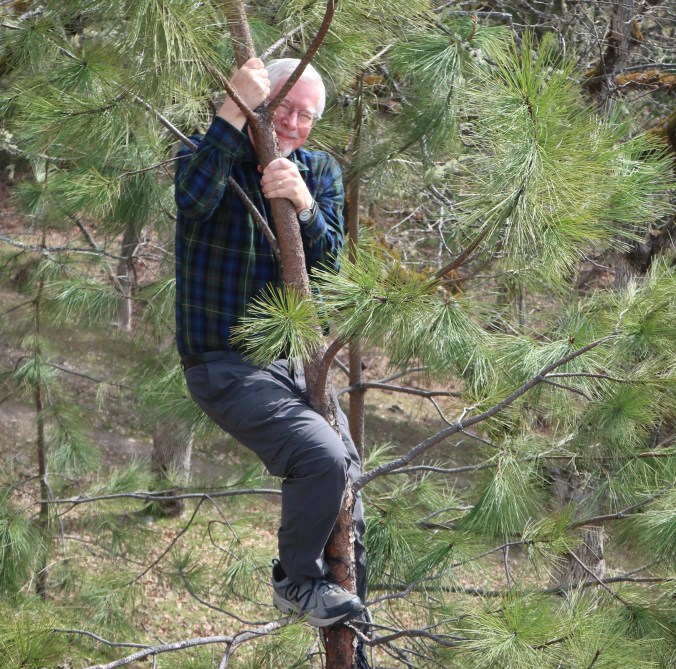

Marshall was taking a teenage time-out with Mother’s parents who had moved to Watsonville, down on the Central Coast of California. Each day I went to the Graveyard and took several practice-runs up the tree. I became half monkey. Each limb was memorized and an optimum route chosen. Tree climbing muscles bulged; my grip became iron and my nerves steel.

Finally, the big day arrived and Marshall came home. He was every bit the big brother who had been away at high school while little brother stayed at home and finished the eighth grade. He talked of cars and girls and wild parties and of his friend Dwight who could knock people out with one punch. I casually mentioned the possibility of a race to the top of the tree. What a set up. As a two pack-a-day, sixteen-year-old, cigarette smoker he wasn’t into tree climbing, but how could he resist a challenge from his little brother.

Off we went. Marsh didn’t stand a chance. It was payback time for years of big brother hassles. I flew up and down the tree. I hardly touched the limbs. Slip? So what, I would catch the next one. Marsh was about half way up the tree when I passed him on my way down. I showed no mercy and greeted him with a grin when he arrived, huffing and puffing, at the tree house.

His sense of humor was minimal. Back on the ground, his bruised ego demanded that he challenge me to a wrestling match. I quickly pinned him to the ground. It was the end of the Great Tree Race, the end of big brother dominance, and a fitting end to my years of associating with dead people in the Graveyard.

And Now for the Coatis of Costa Rica

Yesterday, Peggy and I drove from Nuevo Arenal to the tourist oriented town of La Fortuna. It was pretty much what one would expect of a town that makes its living off of separating money from the visitors. There were a ton of things you could do for a price. I don’t have a problem with that. People would get their money’s worth and locals could put food on their tables. But I much preferred Nuevo Arenal.

The highlight of the trip was the band of Coatis we came across on our drive over. There must have been a dozen or so. These diurnal, omnivorous animals are actually related to raccoons. They were spread out alongside the road doing their coati thing. They were easily outnumbered by the people who had stopped to admire them.

And I’ll make my own escape here. Once again, I am going to make a slight change in my blog. I’ve decided to speed up UT-OH, my blog-a-book memoir, so I can indeed turn it into a book. I’ll be pulling out tales from my 15-years of blogging and putting them up in chapters on Mondays and Wednesdays. I’ll reserve Fridays for our travel blog covering our present journeys: Costa Rica now, Greece and the Greek Islands in May, and then Northern Scotland and Ireland in June and July.

In my posts on Monday and Wednesday next week, I am going to relate the two experiences that led to my lifelong love of the wilderness: The Pond and the Woods.